Goblet

Dateca. 1790

Maker

Delftfield Pottery

OriginScotland, Glasgow

MediumHigh-fired, dry-bodied earthenware / Egyptian black ware

DimensionsOH: 8 13/16; Diameter (mouth) 4 3/4in. (22.4 × 12.1cm)

Credit LineMuseum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund

Object number2020-112

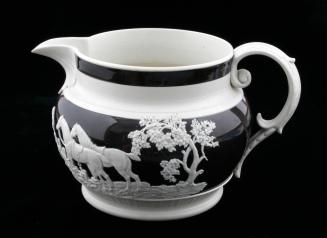

DescriptionGoblet or footed cup: square plinth supports stepped circular spreading foot that rises to four-part mold, slip-cast cup modelled with four satyr faces and overarching ivy vine. Traces of original gilding at the rim, circular base of the foot, and at the juncture of the stem and cup.Label TextThis handsome slip-cast molded goblet is made of a high-fired dry-bodied ware referred to in the period as "Egyptian black" because the body mimicked the appearance of Egyptian or Etruscan pottery. Wedgwood's term for his patented version of the ceramic body was "black basalt." But other potters throughout Great Britain and Europe were attempting to make a similar material, as well, and it is often listed in inventories and newspapers as "Egyptian" or "Egyptian black."

An extremely rare object and one of only three examples attributed to the Delftfied pottery in Glasgow, Scotland, this goblet is most likely the result of some of James Watt's experiments with ceramic body types and his discussions of materials and techniques with Josiah Wedgwood. The piece retains traces of its original gilded border at the mouth of the vessel and additional traces of gilding on the circular part of the goblet's foot and at the juncture of the cup's stem and bowl.

While Colonial Williamsburg has in its collection examples of Delftfield's tin-glazed earthenware products, this footed cup, dating to around 1790, illustrates the later phase of production and experimentation at that important pottery.

Established in 1748, the Delftfield pottery has an interesting history that ties it closely to Virginia. Laurence Dinwiddie, brother of Virginia's colonial governor Robert Dinwiddie, was one of the factory's founders. Robert had made his fortunes in the tobacco trade and Laurence convinced him to be a co-investor in the Delftfield pottery endeavor. Both the documentary and archaeological records reveal the export of the Delftfield pottery's wares from Glasgow to Virginia, especially during Robert Dinwiddie's tenure as royal governor. (John Austin wrote about the tin-glazed earthenware trade and Janine Skerry and Suzanne Hood published on the salt-glazed stoneware export/import market for Delftfield's products.) After Laurence died in 1763, his portion of the pottery passed down to his son who maintained an active role in the pottery and was probably instrumental in encouraging James Watt to invest in the manufactory, as well.

The Scottish inventor and entrepreneur James Watt is best known to us today for his role in improvements to the steam engine. But he had his hands in many pots (no pun intended) and is credited with reviving the Delftfield pottery beginning in the mid-1760s. Watt took over management of the manufactory and became an active participant in the financial and potting sides of the business; not only did he help support it as an investor, but he also shared formulas and recipes for stoneware and refined earthenware bodies, numerous glazes, and improvements for painted and printed decoration. While we often associate Watt his like-minded friends and fellow entrepreneurs Matthew Boulton and Josiah Wedgwood, Watt actually first became acquainted with Wedgwood (and subsequently Boulton) through his role at the Delftfield pottery.

Even after Watt relocated from Glasgow to Birmingham, he stayed involved with the Delftfield pottery, picking Wedgwood's brain, and sharing technological advancements in ceramic body and glaze developments with his colleagues at Delftfield. Watt died in 1819 and the Delftfield pottery closed by 1826.

1790-1810

ca. 1770

ca. 1770

1827-1838

1827-1838

1827-1838

1827-1838

ca. 1785

ca. 1785

ca. 1725

ca. 1810