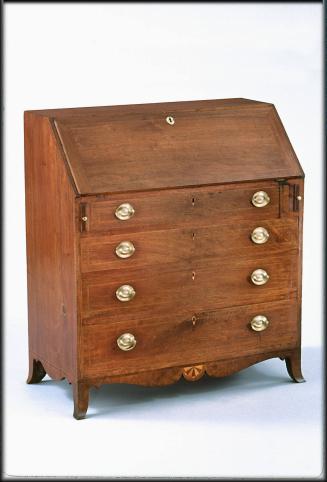

Chest of drawers

Date1780-1795

MediumMahogany and yellow pine.

DimensionsOH: 36 1/2"; OW: 42 1/4"; OD: 20 1/2"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1967-99

DescriptionAppearance: Chest of drawers with four graduated tiers of drawers, two short over three long; unmolded top; scratch-beaded drawer fronts; quarter round base molding; four straight bracket feet.Construction: The top of the case is attached to the sides with blind-mitered dovetails. The bottom is dovetailed in the usual fashion. The drawer blades are tongue and grooved to dustboards of the same thickness, and are set into dadoes that run the full depth of the case. The dustboards stop about two inches from the backboards. Thick veneer strips glued to the front edges of the case sides conceal the drawer blade joints. A four-inch-deep mahogany divider that separates the top drawers is set into dadoes above and below that run the full depth of the case. Pairs of thin rectangular blocks with chamfered rear corners are glued and nailed to the drawer blades and act as stops for the drawers. Four tongue-and-groove vertical backboards are nailed into rabbets along the top and sides of the case and are flush-nailed at the bottom. The base molding is glued to the edges of solid yellow pine blocks that are in turn glued to the case bottom and run the full width of the front and sides but extend in only six inches from each side at the rear. The dovetailed bracket feet are glued to the undersides of these strips. Pairs of mitered horizontal mahogany blocks are glued to the strips just inside each foot. They are shaped to match the bracket faces. The bracket feet are further braced with three-part, laminated, vertically grained glue blocks.

The drawers have scratch-beaded fronts and exhibit standard dovetailed construction. The drawer bottoms are deeply beveled along the front and sides. They are nailed into rabbets at the front and sides and are flush-nailed at the rear. The bottoms are reinforced along the front and sides with full-length glue strips that are butted at the front corners and mitered at the rear. The front strips exhibit small notches that accommodate the drawer stops.

Materials: Mahogany top, sides, drawer fronts, drawer blades, drawer divider, front edge veneer strips, exposed parts of feet, and horizontal foot blocks; all other components of yellow pine.

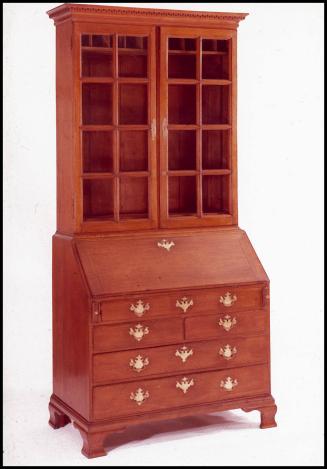

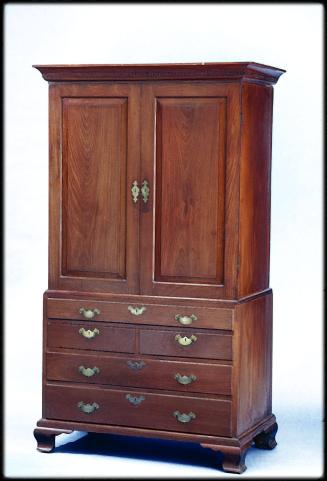

Label TextLike Virginia's other fall-line towns, Petersburg became an important trade center during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Situated at the head of navigation on the Appomattox River, the town was the principal marketplace for a vast and fertile agricultural region that stretched west into the Piedmont and south into north central North Carolina. Planters large and small brought their valuable tobacco crops to Petersburg for transhipment to Norfolk and then Europe. In turn, they purchased textiles, ceramics, and other imported goods from the city's large mercantile community. Concurrently, newly arrived furniture makers began to supply cabinet wares to householders throughout region. Petersburg supported at least four full-time cabinet- and chair making shops during the 1780s, and the number tripled during the following decade. By 1795, ambitious firms like Swan and Ellis (w. 1795-1797) confidently advertised that they were capable of producing "all kinds of Cabinet work: such as Easy Chairs, Chairs, Sofas, Secretary and Bookcases, Desk and Bookcases, circular, square, and oval pembrook, Card and Dining Tables, circular and commode sideboards with celarates, circular, square and commode Beaurous, and many other articles too tedious to mention." Surviving artifacts confirm that Petersburg artisans made these forms and many others.

The British neat and plain taste that characterized furniture from eastern Virginia cities like Williamsburg and Norfolk was strongly favored in Petersburg as well. This Petersburg chest of drawers clearly illustrates the trend. Outwardly, the design emphasizes good proportions and clean, spare lines. Even the top edges are devoid of superfluous projecting moldings. Within, the joinery reveals high levels of care and precision. This is especially evident in the long rows of fully concealed and mitered dovetails that join the top of the case to the sides. The execution of such joints was far more complex and time consuming than the installation of a molded edge; its presence here demonstrates that the simplicity of the chest's exterior does not represent attempts to save on labor or costs.

American case furniture with flush upper edges is rare, but British pieces survive in some numbers. British artisans first employed the motif near the end of the seventeenth century when they began to produce "japanned" copies of the lacquerwork cabinets then being imported from China. A standard element in Chinese cabinet work, the flush-edge top was eventually incorporated into conventional European forms like the chest of drawers and the bureau table. Later still, the design made its way to Petersburg and a few other American cities, almost certainly via immigrant British artisans. It is improbable, however, that Virginians who owned chests like the CWF example were aware of the design's Asian origins. Instead, they likely viewed such details as nothing more than expressions of the latest British taste, clearly a strong selling point for the region's gentry.

The CWF chest of drawers is part of a large and cohesive Petersburg shop group characterized by several structural and design details. Among them are straight bracket feet with a quarter-round base molding, drawer fronts with fine scratch-beaded edges, drawer bottoms with unusually wide bevels (up to twelve inches), dustboards that stop a few inches short of the back and are the same thickness as the drawer blades, and three-part vertically laminated foot blocking. Most of the objects that exhibit these details in combination have histories of ownership in areas for which Petersburg served as the principal commercial center. For example, this chest of drawers descended in the Michel family of Brunswick County, about forty miles southwest of Petersburg. An identical chest has a history in Orange County, North Carolina, another area that traded directly with Petersburg, and a Petersburg collector owned a third early in the twentieth century. Other products from the shop include a desk made for the Gilliam family of Amelia County, Virginia, about twenty miles west of Petersburg, and a desk and bookcase that descended in the Grigg family of Dinwiddie County, on the town's southern border (CWF acc. 1991-433.

Based on stylistic evidence alone, one could safely ascribe to these pieces a production date in the 1760s or 1770s, but it is likely that some or all were made after the Revolution. Supporting this observation is a black walnut desk that appears to be from the same shop. Virtually identical to the other desks in the group, it retains original late eighteenth-century brasses in the form of neoclassical ring pulls. The date 1801 written inside one of the interior drawers probably refers to the year when the desk was produced. The cause of this stylistic conservatism lies in Petersburg's trade patterns. After the Revolution, the town's participation in Virginia's international trade network was severely hampered by the economic devastation visited upon coastal trading partners like Norfolk. Interaction dropped off sharply, and, while Petersburg remained important as a regional market, contacts with coastal design centers were reduced. Consequently, while cabinetmakers in Norfolk and Alexandria embraced the newly introduced neoclassical taste, many of their counterparts in Petersburg continued to produce the same kind of conservative neat and plain furniture they had built before the war.

InscribedNone

MarkingsNone

ProvenanceThe chest was purchased in 1967 from Williamsbrug antiques dealer William E. Bozarth. He acquired it from the Michel family of Brodnax, VA, near the Mecklenburg-Brunswick county line.

Exhibition(s)

1750-1775

1760-1780

1804-1813

1797-1800

1750-1760

1760-1780

1760-1780

ca. 1775

ca. 1800

1790-1805

1760-1790

1805-1815