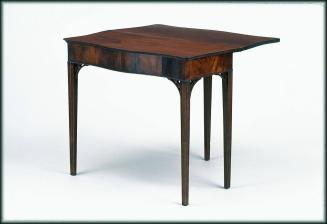

Sideboard table

Date1765-1785

MediumCherry and tulip poplar.

DimensionsOH: 34 7/8"; OW: 52 5/8"; OD: 27 7/8"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1975-84

DescriptionAppearance: rectangular top molded on front and sides; straight rails, all with scratch beading on lower edges (left side rail beaded on upper edge as well); four Marlborough legs, each chamfered on inner edge, scratch-beaded on right and left edges, and with an inset ovolo molding on leading edge; pierced fretwork brackets on front and sides; solid brackets of simple profile on rear. Construction: The top consists of two butt-joined boards and is molded only along its front and side edges. It was originally secured to the frame with four screws set into wells in the front and rear rails. Additional support came from twelve widely spaced chamfered glue blocks, three on each rail. The rails are tenoned and double-pinned to the legs. Each knee bracket is attached with four wrought brads (two in each terminus) and backed with two long, thin, chamfered glue blocks mitered at the corners. A cabinetmaker's mistake is evident on the left side rail, the upper edge of which carries the same scratch bead found on the lower edges of all the rails.

Materials: Cherry top, rails, brackets, and legs; tulip poplar glue blocks under top and behind knee brackets.

Label TextThis cherry sideboard table executed in the neat and plain style exhibits structural and decorative details common to eastern Virginia and Maryland tables of many shapes and sizes. Elements typical of the Chesapeake school include the heavy chamfering on the legs and the inset ovolo molding on their leading edges. Scratch beading like that on the rails and the inner edges of the legs was also widely employed in the region, as were fully finished backs. Here the concealed rear rail was not only made of cherry like the exposed parts of the table, but was carefully planed, beaded, stained, and finished to match the front and side rails. The rear elevation even features a pair of almost unseen knee brackets that balance those on the front and sides, although they are solid instead of pierced. Finally, like many other Chesapeake tables, the top of this one is secured to the frame with a series of small, evenly spaced glue blocks.

Despite the generic nature of these conventional British woodworking details, the table's long history at Ayrfield plantation on the rural Northern Neck of Virginia and its execution in cherry point to local production or in the nearby Rappahannock River basin, where cherry was one of the most favored cabinet woods in the late colonial period. Several tables of similar character have Northern Neck histories, among them a writing table that also descended at Ayrfield and appears to be from the same shop that produced the sideboard table. Now missing its brackets, the top boards of the writing table are joined with wooden butterfly cleats like those used in house paneling, and the drawer bottom is flush nailed on all four sides instead of being set in grooves on the front and sides. These details suggest that both tables were made by a joiner.

In 1782, British immigrant joiner James Woosencroft performed a variety of tasks for Robert Carter at Nomini Hall plantation, including "altering 2 brick moulds," "repairing the Chariot Carrage," "Spliceing 1 pr of Compesses for Coupers," and providing "1 Coffee pot handle." He was also paid one pound for "makeing 1 wallnut table with open brackets," an apt description of the Ayrfield writing table. It is tempting to assume that the versatile Woosencroft also made the tables at Ayrfield, which was less than ten miles from Nomini Hall. However, a firm location-specific attribution for these tables must await the discovery of additional objects that were made by the same hand and retain their early ownership histories or some form of documentation.

The basic design of the CWF table resembles that of a "Sideboard Table" illustrated in plate LVI of the third edition of Chippendale's DIRECTOR (1762), although the proportions and dimensions differ somewhat. In an explanation of his design, Chippendale noted that the measurements of "Side-Boards" should "vary according to the Bigness of the Rooms they stand in." The lighter scale of the Virginia table is in keeping with contemporary Virginia houses, the largest of which was far smaller than the dwellings of the British aristocracy for whom Chippendale often worked. The overall delicacy of scale on the table may also indicate production in the 1780s on the eve of the neoclassical movement in Virginia.

InscribedNone

MarkingsNone

ProvenanceThe first owner of the table was probably Scottish immigrant John Ballantine, who acquired property in Westmoreland Co., Va., in 1769. The estate, which he named Ayrfield, descended to his daughter, Anne Ballantine, and her husband, John Murphy, who replaced the earlier house on the site in 1806. The table remained at Ayrfield until 1975, when it was sold to CWF by Hope Alice Murphy Whittaker, a direct descendent of the original owner. Ayrfield and most of its remaining early contents were destroyed by fire in 1994.

1810-1820

ca. 1760

1810-1820

ca. 1765

1765-1790

1750-1775

ca. 1800

1815-1825

1760-1780

Ca. 1770

ca. 1800

1770-1789