Armchair

Date1790-1815

Attributed to

Monticello Joinery

MediumCherry (by microanalysis), webbing, linen, tow, hair, leather, brass

DimensionsOH: 34 7/8”; SH: 18”; OW: 23 ¼”; SW: 20¼”; SD: 18¾

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1994-107

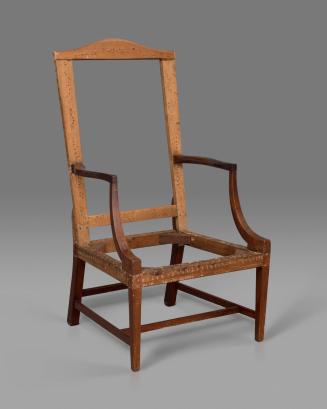

DescriptionAppearance: Open armchair with black leather half-over-the-rail upholstery, secured with round-headed brass nails over an additional thin leather strip; strapwork splat consisting of interlaced ellipsoids; sloping arms with additional curved braces below; serpentine arm supports that continue down to form front legs, which are tapered only on inner surfaces; plain seat rails; rear stiles with scratch-based borders continue to scratch-beaded borders continue to floor to form gently curved legs.Construction: The crest rail is mortised to receive the tenoned upper ends of the stiles. The splat is tenoned into the crest, stiles, and stay rail in seven places. The stay rail, in turn, is tenoned into the stiles. Both the arms and the small curved braces below them are through-tenoned into the stiles. The arm supports are tenoned into the underside of the arms. The side seat rails are through-tenoned into the rear legs. Other seat joints exhibit traditional blind tenons.

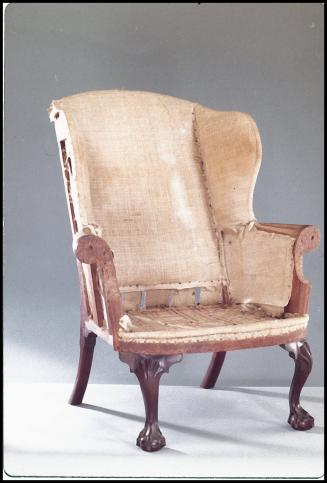

Upholstery: Thick, tow filled linen upholstery rolls are tacked to the outside faces of the seat rails and supported by tacks in the rear stiles 2 ½ in. above the seat rails; several horizontal rows of running stitches shape rolls. Cavity filled with hair stuffing. A layer of linen is tacked into a shallow rabbet at top of outside faces of seat rails. A second layer of stuffing and linen is attached to the front arm supports; profile of front edge of upholstery is approximately 1 inch higher than the rear edge of upholstery. Leather show material tacked into tacking rabbet and covered with 3/8 in. wide strip of leather secured with brass nails 1 inch apart.

Materials: All wooden components of cherry (by microanalysis); webbing, tacks, tow and hair stuffing; foundation linen and top linen, black leather show cloth, brass nails.

Label TextThe site of Thomas Jefferson's lifelong experimentation with architectural design and neoclassicism, Monticello was a bustling and largely self-sufficient plantation community. The Monticello "family," as Jefferson termed it, included a number of enslaved artisans who worked in a row of shops near the main house. Among the facilities was a "Joinery" where most of Monticello's architectural woodwork and some of its interior furnishings were fabricated. Described in 1796 as a "joiner's shop, 57. feet by 18. feet," the building was home to several artisans and a full range of woodworking tools, including a large lathe.

The history of the Monticello joinery can be divided into two periods. One spanned the last decades of the eighteenth century and the initial years of the nineteenth; the second extended from 1809 to 1826. During the earlier period, Jefferson hired a series of free white woodworkers who were charged with overseeing day-to-day operations at the joinery and instructing selected slaves. Among these paid artisans were David Watson, James Dinsmore (ca. 1771-1830), James Oldham, and John Neilson (d. 1827), most of whom were British immigrants. The principal slave artisan at the joinery was John Hemings (b. 1775), who apparently worked for all of the first-period master joiners. Identified by contemporary observers as "a first-rate workman," Hemings became a highly skilled carpenter who was also conversant with a wide range of other skills.

The joinery's second period, which began when Jefferson left the Presidency and retired to Monticello in 1809, is distinguished by Hemings's emergence as the primary woodworker. By then, the former president was financially strapped and less able to afford hired artisans or commercially made furniture. As Jefferson continued the constant rebuilding of Monticello during these years, he came to rely ever more strongly on the skills of Hemings and other slaves. Operations at the joinery ceased with Jefferson's death in 1826. His will stipulated that Hemings and several other enslaved craftsmen be freed and that they be provided with the tools of their respective trades.

Jefferson introduced the immigrant British woodworkers and their enslaved African-American counterparts to the French neoclassical style. Between 1784 and 1789, Jefferson served as American ambassador to France. While there, he acquired a large assortment of sophisticated French furniture, much of which was sent to Monticello. Among the items Jefferson brought home was a set of fauteuils, or armchairs, made by Parisian cabinetmaker Georges Jacob. With their squared upholstered backs, ascending arms, and saber legs, the Jacob chairs clearly served as the models for a mahogany armchair that was made in the joinery and descended in the Steptoe family. Strong French and other continental influences are also evident in two sets of joinery-made side chairs with tablet-form crests (CWF# 2015-164) and in a circular table with tapered legs. Coarsely constructed of cherry, the table was embellished with a marble slab and pierced brass gallery that Jefferson brought back from Paris. French influence may be detected in a black walnut and mahogany seed press that Jefferson ordered from the joinery about 1809. The forward-facing stiles and rails that frame its paneled doors have mitered corners, an approach rarely used on case furniture yet one that also defines the back frames on the Jacob chairs.

The CWF armchair echoes a number of designs and details from the joinery's French-inspired productions. Diverging considerably from most Piedmont Virginia chair-making traditions, the square stance and upswept arms of this chair clearly relate to the same elements on the Jacob chairs, elements that the joinery staff also employed on the Steptoe chair. The definition of the back panel by a bead run on all four sides similarly emulates the backs of the Jacob and Steptoe chairs, although the coarsely rendered scratch beading on the CWF chair does not approach the delicate quality of the molded edge on the French model. The dramatically tapered legs on the CWF chair also relate closely to those on the tablet-back chairs. Like most other chairs made at the joinery, the one shown here also features mortise-and-tenon joints secured with small pins. The CWF chair differs from presently known joinery models in that its side seat rails are tenoned through the rear posts. It is worth noting however that three of Jefferson's hired joiners--Dinsmore, Oldham, and Neilson--spent time in Philadelphia where through-tenon construction was common.

The original upholstery on the chair also supports an attribution to the Monticello joinery. While the upholstery techniques are not-traditional, they are effective and have held up well over time, suggesting a craftsman with a broad knowledge and keen intuitive skill, but not specific training in upholstery. The materials of the foundation upholstery suggest a French origin, which is conceivable in the Monticello joinery, as Jefferson was known to purchase household goods from France in this period; alternatively, they could have been repurposed from a chair Jefferson brought from France. The iron upholstery tacks may indicate local production because Jefferson established a nailery at his estate in 1794.

Also lending credence to the chair's Monticello attribution is its history of descent in the Nicholas family. The chair could not have been purchased by Robert Carter Nicholas in 1776, as family tradition states, but it did descend through his family. In 1781, Nicholas's widow, Anne Cary Nicholas, moved her family from Williamsburg to Albemarle County where they renewed strong ties with Jefferson, whom they had known from his pre-Revolutionary days in Williamsburg. Anne Nicholas's oldest son, George (ca. 1754-1799), worked with Jefferson on the Antifederalist resolves in 1798, and his brother, Virginia governor Wilson Cary Nicholas (1761-1820), was Jefferson's political protégé and lifelong friend. The ties continued when Wilson's daughter, Jane, married Jefferson's financial manager and favorite grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1792-1875), in 1815 and took up residence at Monticello. When Wilson Cary Nicholas died in 1820, he was buried in the Jefferson family cemetery at Monticello.

In summary, physical and historical evidence point to an attribution of this chair to the Monticello joinery. Additional research is needed to understand the full range of the shop's traditions and to identify more of the artisans at work there. Further attention must also be paid to the shop's regional influence. In the meantime, this chair and other French-inspired products from the shop are intriguing examples of Thomas Jefferson's role in the development of a distinct Franco-Piedmont furniture style.

InscribedThree illegible digits are written in ink on the front of the stay rail.

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceThe chair was probably owned first by Anne Cary Nicholas or one of her children, all of whom resided in Albemarle Co., Va., beginning in 1781. According to family tradition, it eventually passed to her son, Philip Norborne Nicholas (ca. 1775-1849), then to his son, and finally to the latter's daughter, Elizabeth Cary Nicholas. In June 1917, she sold the armchair and a British side chair from the same set as CWF accession 1985-260 to Fanny Morris Murray, New York, N. Y. The armchair then descended to Mrs. Murray's son, Henry Alexander Murray, and to his daughter, Dr. Josephine Murray, from whom CWF purchased it in 1994.

1766-1777

1750-1770

1750-1770

1750-1760

1750-1760

ca. 1730

ca. 1765

ca. 1790

1790-1810

ca. 1765

1795-1805

1780-1800