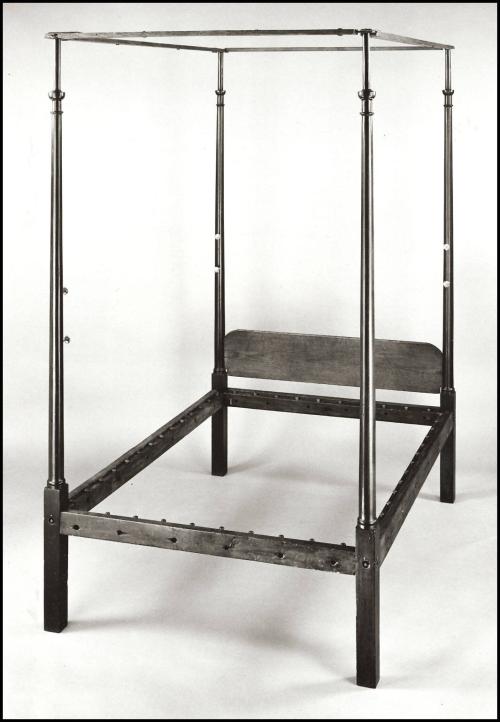

High-post bedstead

Date1790-1810

Attributed to

Samuel White

MediumMahogany posts, red gum (Liquidambar styraciflura) rails (by microanalysis), yellow pine headboard and pulley lath.

DimensionsOH: 98"; OW: 53"; OD: 75"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1978-30,1

DescriptionAppearance: Straight turned head and foot posts; unmolded square feet; simple headboard with rounded top corners; double cloak pins at center of each post; pulley lath with pulleys positioned for double drapery; the top twelve inches of each post is tenoned to the rest of the post; this original joint is concealed by the upper turned element which acts as a collar, slips over the post, and rests on a turned rabbet on the lower section of the post; posts and collars now glued.Construction: The rails are tenoned into the leg posts and secured with large iron bed bolts seated into fixed nuts in the rails. The headboard is tenoned into the head posts. A series of turned pegs are tenoned into the tops of the rails and were used for tying on the sacking bottom that originally supported with mattresses. The top twelve inches of each post is tenoned to the rest of the post, and the joint is concealed by a turned collar that slips over the post and rests on a turned rabbet. The head and foot elements of the pulley lath are through-tenoned into the side elements, and the assembled frame rest on iron pins that project from the tops of the posts. The wooden pulleys are mounted on iron axles.

Materials: Mahogany posts; *red gum rails; yellow pine headboard and pulley lath; probably maple pulleys; iron pulley axles.

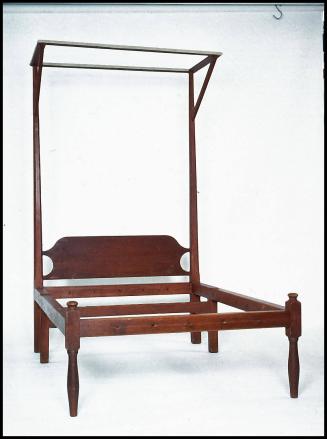

Label TextAlthough bed curtains are often viewed as decorative accessories today, they were originally functional components of a high post bed. In the winter, the closed curtains provided protection from the subfreezing indoor temperatures common before the advent of central heating. During the summer, gauze mosquito curtains were often substituted to ward off insects. Textiles used for bed curtains ranged from relatively expensive worsted wools to printed cottons to woven checks and stripes. Most were imported from Great Britain.

Curtains could be attached to a bedstead in several ways. One of the most complex is illustrated by this Virginia bedstead, which retains its original lath frame. Resting atop the posts, the frame is fitted with eighteen pulleys over which cords were placed for drawing the curtains up in what was known as drapery. When the curtains were raised, the cords were tied off around pairs of brass cloak pins screwed into each of the four posts. A lath frame with a similar pulley configuration is illustrated in Chippendale's 1754 Director, which confirms the double drapery pattern originally intended for this bed.

Bedsteads of this high quality were generally topped by ornamental cornices, of which few have survived. Period graphics like the Director and documents such as the 1768-1775 accounts of Charleston cabinetmaker Thomas Elfe demonstrate that cornices came in a wide array of forms.

Eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century bedsteads in the plain style offer few clues about where they were made, but this one bears structural details that permit a firm shop attribution. The bed rails are made of red gum (Liquidambar styraciflua), a wood rarely used for that purpose in American cabinetmaking. Even more unusual is the construction of the four posts. Probably because the size of the artisan's shop or his turning lathe could not accommodate eight-foot-long stock, the upper nine inches of each post was turned separately and tenoned in place. The resulting joint was concealed by a wooden collar slid over the post and glued into a turned rabbet. Both of these novel details appear on a closely related bedstead at Prestwould, the Mecklenburg County, Virginia, estate built for Sir Peyton and Lady Jean Skipwith in the 1790s. The Skipwiths' accounts reveal that Petersburg cabinetmaker Samuel White (w. 1790-1829) made their bedstead in 1798. With a history in Dinwiddie County just outside Petersburg, it is clear that White made the CWF bedstead as well.

Among the more than thirty pieces of furniture White made for the Skipwiths between 1790 and 1798 were six high post bedsteads, including a field bed that retains its original double-ogee tester frame and finials. White also made a set of dining tables, a lady's work table, a "gothick book-Case," a "French Sohpy," and a "Cabriole Chair," the latter demonstrating his skill as an upholsterer and his familiarity with published design sources such as Hepplewhite's 1794 Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer's Guide.

Nothing is known of White's training or origins, but his active role in the Petersburg furniture trade for nearly forty years suggests that he was a successful businessman. Like most cabinetmakers, White was also active in the funeral trade. The town of Petersburg purchased many of his cheapest coffins in which to bury the poor. In 1816, White and another local cabinetmaker, Alexander Taylor, Jr., were nominated coroners for the town. When Taylor died in 1820, his estate inventory included "1 Old Hearse and Harness" jointly owned by "Taylor and White."

At his death in 1829, White left an array of cabinetmaking tools, an ample supply of cabinet woods, a copy of the Dictionary of Arts & Sciences, and some unfinished goods, including "1 Sofa frame & Easy Chair." The estate was valued at over $3,600, a considerable sum for the time.

InscribedNone

MarkingsThe posts are marked at the rail mortises with incised Roman numerals "I" through "VIII." The rails are similarly marked at the tenons.

ProvenanceThe bedstead was purchased in 1978 from the owners of a late eighteenth-century house in Dinwiddie Co., Va. The bed had been used in the house since the late nineteenth-century and possibly earlier.

1793

1750-1765

ca.1830

1760-1780

Ca. 1770

1780-1800

1840-1850

Ca. 1825

ca. 1760

1815-1820

1740-1800