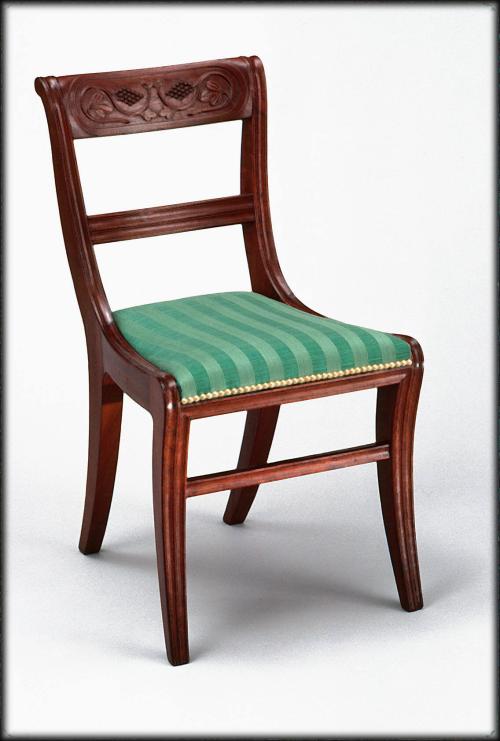

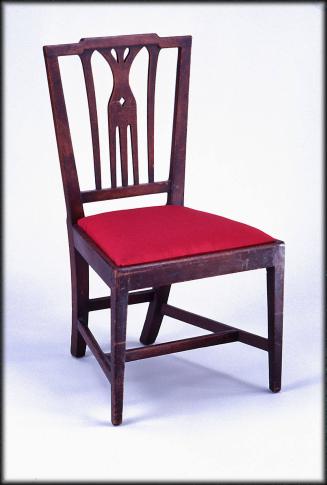

Side chair

Date1815-1825

Attributed to

William King Jr.

(1771 - 1854)

MediumMahogany, white pine and tulip poplar

DimensionsOH: 32 3/4"; OW: 17 7/8"; OD: 15 1/4"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1994-137,2

DescriptionSide chair with tablet back, rounded at top, carved with a meandering grape vine; molded rectangular stay rail; slightly arched stiles; trapezoidal upholstered seat; saber legs and front stretcher; fronts of stiles, legs, stretcher, and front seat rail molded.Label TextAs the federal government expanded after 1800, the population of the District of Columbia continued to grow and the local cabinet trade followed suit. Although imported furniture from northern centers was still plentiful in the nation's capital, nine full-fledged cabinetmaking shops had been established in "Washington City" by 1820. At least three more thrived in neighboring Georgetown, the Potomac River port annexed from Maryland when the federal District was created in 1791. Responding to the needs of everyone from those who aspired to middle-class status to wealthy foreign diplomats, these shops generated a wide variety of household furniture, some of it quite sophisticated.

One of the leading figures among District furniture makers of that period was William King, Jr. (1771-1854), whose Georgetown shop almost certainly produced a mahogany sofa (CWF acc. 1994-137, 1) and a set of matching side chairs (including this example) about 1820. A native of Ireland, King immigrated to America with his parents on the eve of the Revolution. According to family records, he served an apprenticeship in the Annapolis, Maryland, shop of cabinetmaker John Shaw (1745-1829). King completed his training in 1792 and almost certainly worked as a journeyman in Shaw's shop for another year or more. By 1795, King had moved to Georgetown, where he established a cabinet business that remained in continuous operation until his death in 1854, an impressive run of some fifty-nine years.

That the community held King’s wares in high regard is suggested by a commission he received--probably in 1817--from the administration of President James Monroe. In order to replace furnishings destroyed by British troops during the War of 1812, King was asked to make nearly thirty pieces of furniture for the recently reconstructed White House. Late in 1818 or shortly thereafter, King delivered a suite of four large sofas and twenty-four fully upholstered armchairs that served as the principal furnishings of the East Room until 1873 (examples of which are now in the White House and Smithsonian collections). Made of mahogany, these pieces were executed in the latest style and may well have been inspired by a suite of carved and gilded chairs purchased for the executive mansion in 1817 from Parisian artisan Pierre-Antoine Bellangé.

Among King's other prominent clients were Clement (1776-1839) and Margaret Claire Bruce Smith (1783-1862), residents of Georgetown and first owners of the side chair illustrated here. A well-connected businessman, Clement Smith was the president of the Farmer's and Merchant's Bank in Georgetown. When he died in 1839, Smith left an estate valued at $50,000, a substantial sum for that day. Probably one of two "Hair Seat Sofas" listed in Smith's probate inventory, sofa #1994-13,7 1 and its matching side chairs, including this example, were arranged in a pair of elegantly furnished rooms that also contained expensive carpets, window curtains, mirrors, a piano, a vast array of silver, and such niceties as "1 Gilt Table & Slab."

Although the White House chairs and sofas represent the only documented examples of King's furniture, nearly a dozen other objects with strong and well-founded traditions of production in King's shop survive in that family. Among them is a mahogany Grecian sofa that is identical to the Smith family example in dimensions, form, and all ornamentation except for the crest rail, which is reeded rather than carved. Other family-owned pieces with credible early traditions of production by King include two library bookcases, a tall clock, and a number of chairs.

Several undocumented objects can be associated with King on the basis of structural and design relationships. For instance, the rosettes on the arm terminals of the CWF sofa (1994-137, 1) were clearly carved by the same individual who produced the floral panels of the arms of the White House suite. The petals and leaves were laid out and veined in exactly the same way on all the pieces. In similar fashion, the carving on the legs of a card table with a long history in the Bradley family of Washington parallels that on the arms of the White House pieces (CWF acc. 1994-106). The ridges and veins of the carved leaves are arranged identically in both cases, although they are quite different from those on most American furniture of the period.

Although little else is known about King's furniture-making operation, much more has been discovered about his activities as an undertaker. Funeral services and supplies accounted for a significant portion of King's business, as they did for most eighteenth- and nineteenth-century cabinetmakers. King's "Mortality Books," the only part of his shop accounts that survive, record the production of an astonishing 7,141 coffins from inexpensive "stained wood" boxes to mahogany caskets lined with broadcloth, between 1795 and 1854.

The services offered by an experienced cabinetmaker like King did not end with the joinery and upholstery involved in coffin making. One of the most complete accounts of his funeral trade survives in the estate records of Clement Smith, whose widow, Margaret, was probably familiar with King as the supplier of the present sofa and matching chairs. At Smith's death in 1839, King provided every mortuary service required by a gentry family. In addition to a "Mahogany coffin lined" and "a case for do.," King billed the estate for the use of his hearse, "horse hire for do.," and the cost of a second horse to walk alongside the hearse. King also arranged for the digging of the grave, paid Washington mason Noble Hurdle for lining it with bricks, brought in workmen to clean the family burying ground, and hired twelve hacks to carry mourners and others from the city to Smith's outlying farm. The total cost of the funeral and related services came to $112.50, about the same price King had charged in 1818 for four of the ornate armchairs he supplied to the White House.

MarkingsIII on underside of front slip seat rail.

ProvenanceThe sofa and seven extant matching side chairs probably were owned first by Clement and Margaret Claire Bruce Smith of Georgetown, D. C. The suite descended to the Smiths' son, Clement Carroll Smith (b. 1819), who apparently moved to New York in the mid-nineteenth century. About 1985, Clement Carroll Smith's descendants sold the suite to Robert Blekicki of the New England Gallery, Andover, Mass. Blekicki sold the objects to a New England collector shortly afterward, but repurchased them in 1994. All eight pieces were acquired that year by antiques dealer Sumpter Priddy III of Richmond, Va. Priddy sold the sofa and one chair to CWF. The remaining chairs were acquired by the D.A.R. Museum and Tudor Place, both in Washington, D. C.

1819-1821

1815

1825-1835

ca. 1815

1790-1810

1795-1805

1800-1805

1790-1810

ca. 1790

Ca. 1790

1760-1790

1770-1775