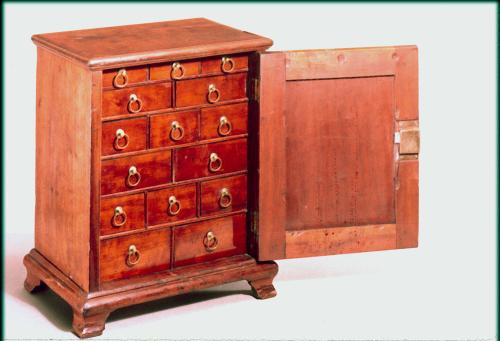

Spice Box

Date1790-1805

MediumCherry and tulip poplar.

DimensionsOH: 18 3/4", OW: 15 3/4", OD: 10 3/4"

Credit LineGift of Katharine Brooke Fauntleroy Bundy

Object number1968-306

DescriptionAppearance: Rectangular box cabinet with single flat-paneled door; flat top with applied edge molding; 15 small interior drawers with ring pulls; drawers separated by cherry dividers and dust boards with rounded nosings; scotia base molding with ogee bracket feet. Construction: The top and bottom of the case are dovetailed to the sides. Cut nails secure the upper molding to the front and sides of the case. The feet are integral with the base molding, which is face-nailed to the lower edges of the case. The vertical blocks behind the feet are downward extensions of the case sides. The door features standard panel-and-frame construction, and its joints are through-tenoned and pinned. The one-piece, vertically grained backboard has downward extensions on its lower edge that serve as the rear faces of the rear bracket feet. The back is set into rabbets along the top and sides, set flush along the bottom edge, and fastened with cut nails. The dustboards are dadoed into the case from the rear, and the drawer dividers are dadoed into the dustboards. The dovetailed drawers have bottoms set into grooves at the front and sides and glued flush at the rear edge.

Materials: Cherry top, top molding, sides, back, bottom, door, feet/base molding, drawer fronts, drawer dividers, and dustboards; tulip poplar drawer sides, drawer backs, and drawer bottoms.

Label TextSmall cabinets with single banks of drawers concealed behind one or two lockable doors usually were known as spice boxes in colonial America, although estate inventories suggest that they were used to store a wide range of materials. In addition to costly spices, these compact and portable boxes also housed currency, documents, jewelry, and personal accessories such as pocket books and spectacles. It is likely that "spice box" accurately described the form's initial use and simply was retained when the multiple drawers proved to be convenient repositories for other small valuables.

Known in Britain by the turn of the sixteenth century, spice boxes were imported to America well before 1700. Several New England examples were produced as early as the 1660s, but most extant American spice boxes date from the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The form was particularly favored by householders in southeastern Pennsylvania. More late colonial and early Federal spice boxes survive from that area than from any other part of the country. Southern spice boxes are rare today, although documents reveal that they were used throughout the region. One of the earliest southern references is in the 1674 probate inventory of Captain John Lee, a Westmoreland County, Virginia, planter who owned "1 Spice box with drawers." Nearly a century and a half later the form could still be found in southern households. In 1816, William Blacklock kept a mahogany spice box valued at the impressive sum of $12 in his Charleston, South Carolina, residence.

Because terminology varied from one area to another, southern ownership of the spice box form may have been even greater than the records suggest. For instance, General Thomas Nelson of Yorktown, Virginia, owned "1 [mahogany] spice press" in 1789. Here, "press" was used in the traditional sense to signify a piece of furniture with doors. In 1782, Williamsburg widow Betty Randolph bequeathed to her niece "the Cabinet on the Top of the Desk." A cabinet was normally understood to be a large piece of case furniture with many drawers enclosed by doors. That Mrs. Randolph's cabinet was small enough to stand on her desk suggests that it actually was a spice box.

The spice box illustrated here has a reliable history of descent from Katherine Brooke Powell (1770-1851) of Middleburg in Loudoun County, Virginia. Middleburg lies in the northern Piedmont, just sixty miles from the Pennsylvania border where spice boxes were especially popular. The Powell family box is unrelated to known Pennsylvania models, however, and is almost certainly a northern Virginia product. The small interior drawers of most Pennsylvania spice boxes are either arranged around a larger central drawer or located above several full-width drawers. The Powell spice box drawers are distributed in a repetitive pattern, with alternating rows of short and long units, like bricks in an English bond wall. While many Pennsylvania spice boxes have back panels that slide into grooves in the sides of the case, the Virginia box has a backboard nailed into rabbets along the rear edges. As yet, there is little documentable Loudoun County furniture with which to compare the Powell spice box, but in light of its strong history in a district where the presence of woodworkers is amply recorded and given the lack of any design or structural relationships to Pennsylvania forms, an attribution to Loudoun or an adjacent county is logical.

The workmanship evident in the Powell box suggests that it was made by an artisan for whom furniture making was not a full-time occupation. The rudimentary construction of the box is more akin to a joiner's or a carpenter's work than to a cabinetmaker's. This is especially evident in the fabrication of the drawers, which, in spite of their small size, are assembled with large, coarsely cut, relatively ill-fitting dovetails.

The unrefined production of small, normally delicate forms is not unusual in areas like the northern Piedmont of Virginia. During the early national period, the upper Piedmont was an agricultural region without cities of significant size, and its widely dispersed population could support relatively few artisans whose time was fully devoted to a single trade. In 1791, Loudoun County woodworker Josiah Dillon promised to teach apprentice Samuel Dillon both house carpentry and cabinetmaking. Dillon's multi-trade expertise was not unusual. The professional description of a rural artisan often was dependent on the goods he was asked to produce at any given time.

InscribedThe numbers one through 15 are penciled on the drawer bottoms and their corresponding dustboards. A mid-twentieth-century textile label glued to the case bottom is inscribed in ink "Katherine Brooke Spice Chest - Property of Katherine Brooke Fauntleroy Bundy."

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceStrong family tradition states that the box was first owned by Katherine Brooke (1770-1851), who married Burr Powell (1768-1839) in 1794 and resided at The Hill in Middleburg, Loudoun Co., Va. The box descended to their daughter, Elizabeth Whiting Powell (1809-1872), and her husband, Robert Young Conrad; to their daughter, Sally Harrison Conrad (1843-1908), and her husband, Archibald Magill Fauntleroy; to their daughter, Katherine Brooke Fauntleroy (b. 1882), and her husband, Henry Clay Miller; to their daughter, Katherine Brooke Fauntleroy Bundy, who presented the box to CWF in 1968.

ca. 1795

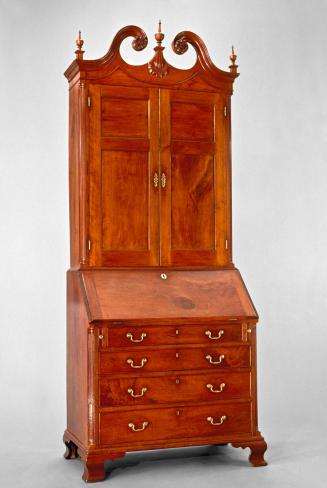

1765-1775

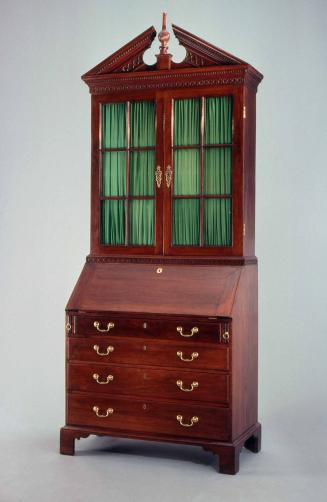

1760-1780

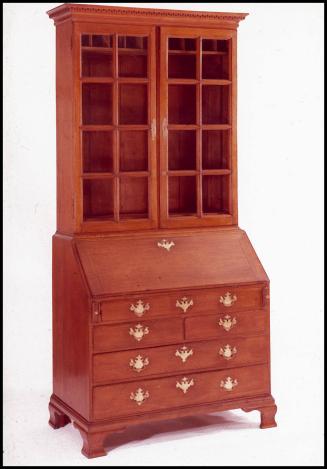

1750-1760

1765-1780

1770-1780

1770-1780

ca. 1795

1797-1800

1815-1830

1710-1725