Portrait of an American Indian Man

Dateca. 1790

MediumOil on canvas, framed

DimensionsUnframed: 28 9/16 x 23 1/2in. (72.5 x 59.7cm) and Framed: 32 1/16 x 27 1/16 x 1 7/8in.

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number2005-84

DescriptionA half-length portrait of an elderly Native American man, seated and turned three-quarters to the left. He gazes up and away to the left, not at the viewer. His proper right arm is extended across his chest, his proper right hand grasping a pipe or pipe tomahawk. A red matchcoat is wrapped around his proper left arm, which extends downward, his proper left hand not shown. He wears an English-style shirt with a ruffled collar and, on his proper right upper arm, a silver armband. From his proper left, distended ear lobe hangs a large, silver, 3-part earring, each part being circular in cross section, the lowermost part, a circle, is suspended from a small oval suspended from a larger oval. His dark hair is fashioned in a scalplock. His eyes are brown, his nose slightly aquiline, his upper lip drawn in and his lower jaw jutting out as though some teeth were missing. Streaks of red paint decorate his chin, temple, cheek, and head. A tuft of reddish brown hair grows in front of his proper left ear. The subject's head appears complete, but the remainder of the composition is relatively sketchily filled in. An incomplete artist change in the proper right hand produced the effect of five, not four fingers. Dark foliage extends diagonally across the middle ground from upper left to lower right, creating an effective backdrop for the sitter's head, with the sky softly lit in front of his face. A horizon line of distant, vegetation-covered ground is visible about halfway up the left side of the picture.

The 2-inch gilded frame is a modern reproduction, derived from a Federal original and provided by Black Dog Gallery 6/2005; it consists of a plain, flat mid section bounded by cyma recta moldings forming both inner and outer edges.

Label TextThe visual credibility of this portrait makes unanswered questions about it all the more frustrating. Scholars suspect the subject of being Iroquois or a member of one of several bands that occupied the southern Great Lakes region, but the widespread adoption of many aspects of the man's attire, accoutrements, and adornment make it impossible to be specific.

Widely used features include the matchcoat (the blanket wrapped over this sitter's near arm), the trade ("English" style) shirt, the silver armband, and the pipe or pipe tomahawk. Many Native men also wore scalplocks like this man's, plucking the hair over most of the head but allowing a patch on top to grow long. The color and application of the paint on the subject's chin, cheek, temple, and ear might seem good clues. Yet face (and body) painting was a very personal aspect of self-presentation, often unique to the individual and based on visions or dreams; as yet, no consistent regional or tribal usage has been documented.

Other features are unusual and thus hold promise for future research. One is the subject's earring. Most Natives dressed in their finest attire for the occasion of a portrait sitting, generally including any of a variety of fancy ear bobs, cones, wheels, and (through slit ears) wire wrappings. By contrast, this man wears what scholars describe as a rather unremarkable "generic" earring. Curiously, no surviving examples of this particular type have been found.

A second, even more surprising feature is the small lock of hair growing in front of the man's ear. At the time the portrait was painted, most Native Americans plucked facial hair, sometimes even eyebrows, so any such growth (but especially one in the form of a "sideburn") is unusual. Also, scalplocks generally were worn by active warriors; its appearance on a man of this one's advanced age (estimated as late fifties or sixties) is unexpected. One conceivable explanation is that all these idiosyncracies derive from simple personal preferences--illustrating how much today's students still have to learn about the variety and diversity of Native American appearance.

The portrait is unsigned. Often such paintings can be attributed to a particular artist on the basis of their style of execution. In this case though, scholars have come to no agreement regarding authorship. Possibilities explored to date include John Trumbull (1756-1843), Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828), and Mather Brown (1761-1831). Distinctive markings on the back of the original canvas reveal that the fabric was supplied by a London "colourman" (artists' supplier). This adds weight to the possibility that the portrait was painted in England (and at one time or another, all of the above-named artists studied in London with American ex-patriot Benjamin West, 1738-1820). It should be noted, however, that similarly stamped canvases also were used in America, if to a lesser extent.

A late eighteenth century date is suggested by the painting's size, format, composition, and general style and by the subject's pose, hairstyle, paraphernalia, and face paint. The original auxiliary support (arrangement of stretchers or strainers that supported the canvas) was removed prior to acquisition, but other physical evidence, such as the canvas, appear compatible with such a date. The colourman's stamp provides little help; it may have been used by 1781 (or possibly even 1775) and continued until 1830.

Typically, portraitists first sketched in their sitters' heads along with other major elements of the composition, but usually heads were brought to a state of finish, or nearly so, before the subsidiary elements. In this painting, the head appears to have been completed, but for unknown reasons, the remainder of the picture was left unfinished. Notice that the artist changed his mind about the positioning of the subject's fingers: originally he wrapped all four fingers around the stem of the pipe or pipe tomahawk; later, he extended the index finger (without, however, obliterating the initial version, thereby giving the subject an extra digit). The painting's unusual survival as a work-in-progress not only illustrates a great deal about this and other period artists' techniques and procedures. It also conveys a rare sense of spontaneity and liveliness, freezing for all time the magical emergence of convincing, illusionistic, three-dimensional form on a two-dimensional surface. Despite its many unknowns, this skillfully rendered and exceptionally penetrating image bears eloquent testimony to the reality of America's first people.

InscribedNone found on the face of the painting. For an old conservator's label and for stamps on the reverse of the original canvas, see "Marks."

MarkingsInfrared photography of the back of the original canvas reveals two stamps now largely obscurbed by the wax lining. The first of these has been deciphered by Jacob Simon (Chief Curator, National Portrait Gallery, London) as a colourman's stamp reading, "J. MIDDLETON 81 St Martins/Lane BRITISH LINEN". Above this, Simon identifies a second stamp, situated within a rectangular frame, as a British excise (internal tax) stamp, stating that it includes a now-illegible year at the righthand end, stamped in small numbers at right angles to the larger numbers. For more Simon feedback on the meaning of this stamp's letters and digits, both legible and illegible, see his email of 4/12/2005 in the file. London colourman John Middleton operated at 81 St. Martin's Lane from at least 1781 (and perhaps as early as 1775) through 1830. See the provisional biography on Middleton provided by Jacob Simon.

Regarding the above excise stamp, Alexander Katlan has stated: "I have found that the 5 box excise mark tends to be earlier in the ca. 1775 to 1830 period than the 3 box excise mark. Thinking that your painting may be from 1810 or earlier may not be inaccurate." [Email Katlan to B. Luck, 7/12/2005, copy in file].

The painting's file assembled by successive former owners Judith Webster and Marvin Sadik includes a 4x5 color transparency of a label once affixed to the back of the painting. (It was removed, apparently by Webster, prior to CWF acquisition). The label was used by Baltimore painting conservator Charles Volkmar, Sr. (1809-1892), and now the transparency and a sketch of it in an undated conservation treatment report of Webster's provide the only record of its existence.

The label, stenciled in black on an octagonal support resembling tin foil, read as follows, the first three words being written in an arc over the remaining ones: "WATER PROOF LINING/&/RESTORING/BY C VOLKMAR/N. Frederick St. No. 8/BALTIMORE." N. B. Volkmar was at 8 N. Frederick Street from 1855 until his death. For more on Volkmar, see "Notes."

ProvenancePurchased by CWF's source, Marvin Sadik, in December 2003 from Judith Webster (d. January 2005 in Richmond, Va.), then living in Chestertown, Md.

Webster aquired the painting in the early 1960s from a secondhand dealer ("Mr. Woolford"; see below), who told her it had come from "an elderly member of an old Baltimore family, 'Tyson'" (Webster to Fawcett-Thompson, 2/7/1969). No Tyson connection has been documented as of 6/9/2008.

A "Mr. Woolford" of the C. & W. Furniture Store (a secondhand shop located at 720 W. Baltimore St., Baltimore, Md.) had indeed acquired the portrait prior to December 8, 1961, at which date one Elizabeth Hanna began contacting various museums on Woolford's behalf, inquiring about appraisals, etc. (see Hanna to Pearce, Smithsonian, 12/8/1961, in file).

As of 6/9/2008, no earlier history has been documented.

Exhibition(s)

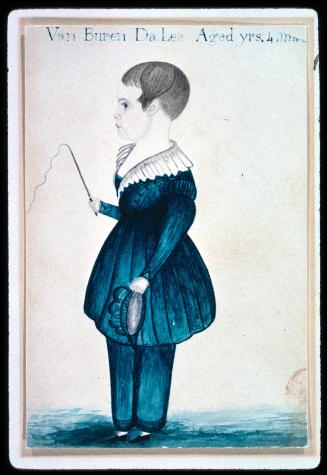

Probably 1841

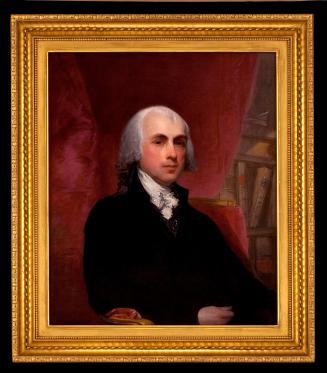

Probably 1770

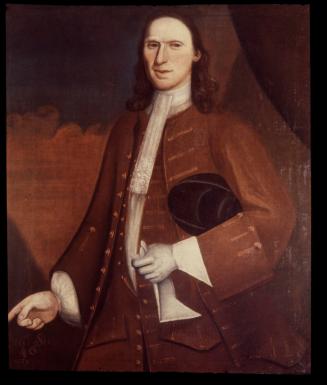

Probably 1665-1700

Probably 1880-1905

ca. 1780