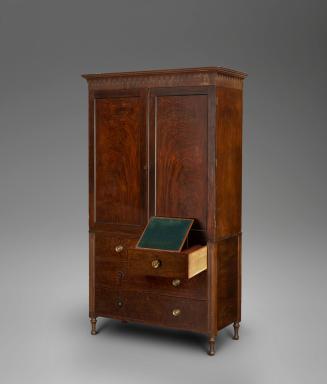

Clothespress with secretary

Date1804-1813

Maker

Thomas Lee

Maker

P. J. Grimball

MediumMahogany, white pine, red cedar, tulip poplar, and yellow pine.

DimensionsOH: 94 3/4"; OW: 50 1/2"; OD: 23 3/4"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1992-175,1

DescriptionAppearance: Clothespress with flat top; cornice with Gothic arches divided by turned drops; 2 flat paneled doors concealing 5 clothing trays; secretary drawer with applied frontal astragal moldings; 3 full-width drawers with cock-beaded edges; original bail brasses with oblong octagonal back plates; straight bracket feet. Construction: The removable cornice consists of a mahogany molding built up on a white pine core, the whole attached to a dovetailed frame. The Gothic arches are integral with the cornice molding, but the turned drops were applied.

The dovetailed upper case has a central drawer blade tenoned into the case sides. The clothing trays run on ledger strips screwed to the case. The back assembly consists of three wide stiles interspaced with two narrow beveled and rabbeted stiles, the whole flush-nailed at the top and bottom and nailed into rabbets at the sides. The door joints are through-tenoned but not pinned. Two large wooden stabilizing pins project from the case bottom into corresponding holes in the lower case. The dovetailed trays have beveled bottom panels set into grooves at the front and sides and flush-nailed at the rear. Each bottom panel is further supported by three short beveled glue blocks at the front and a pair of full-length side strips with mitered rear ends.

The lower case is dovetailed and has a back assembly like that on the upper case. The waist molding is backed with white pine and is nailed to the front and side edges of the top board. Mahogany-faced drawer blades are dadoed to the case and backed with runners that rest in the same dadoes. Vertical drawer stops are nailed to the case sides where they meet the backboards. The base molding is backed by full-length strips glued to the front and sides of the case bottom. Shorter strips extend in from each side along the rear edge. The vertically grained, quarter-round foot blocks are flanked by two thin, shaped horizontal blocks. The cock-beaded case drawers exhibit the same structural details seen on the clothing trays. The bottom of the secretary drawer is set in grooves at each side and reinforced with kerfed full-length glue strips. The top of this drawer is dovetailed to the sides, and the back is nailed on all four sides. Quadrant hinges lower the drawer's fall board. The dovetailed interior drawers have bottoms set into grooves at the front and sides and flush-nailed along the rear.

Materials: Mahogany doors, drawer fronts, case sides, cornice, waist molding, base molding, exposed parts of feet, tray fronts, ledger strips, upper case top and bottom board facings, drawer blade facings, secretary drawer sides, and writing surface; white pine backboards, cornice frame, cornice backing, upper and lower case top and bottom boards, tray bottoms, large drawer bottoms, drawer blades, and secretary drawer framing; red cedar tray backs, tray sides, large drawer backs, and large drawer sides; tulip poplar interior drawer backs, bottoms, and sides; yellow pine foot blocks.

Label TextBritish fashion continued to play a major role in post-Revolutionary Charleston, its popularity easily matching that of newer northern fashions. Writing about the 1790s, South Carolina governor John Drayton (1766-1822) observed in 1802 that "Charlestonians sought in every possible way to emulate the life of London society. They were too much enamored of British customs, manners and education to imagine that elsewhere anything of advantage could be obtained."

For those who were unable or unwilling to order furniture from London, British-style cabinet wares of a more restrained nature were still readily available in Charleston from the many British artisans who came to the city after the war. Despite the political difficulties between the governments of Great Britain and the United States, newly arrived British furniture makers found a strong demand for their skills in Charleston. Among the transplanted craftsmen was Scottish cabinetmaker Thomas Lee (ca. 1780-1814), who built and signed the mahogany clothespress illustrated here.

Lee's British training is apparent in both the overall form and the details of this press. With its secretary drawer and removable cornice, the piece parallels many surviving British examples. The resemblance was heightened by Lee's decision to model parts of the press on illustrations in The Cabinet-Makers' London Book of Prices, and Designs of Cabinet Work, an English manual first issued in 1788 and expanded in 1793. The plan for the interior of the secretary drawer was copied closely from plate 8 in the 1793 London Book, while the Gothic cornice with its turned drops was likely taken from plate 3.

The date of Lee's departure from Scotland is unknown, but he was working in Charleston by 1804 and remained there until the end of his life. His Scottish origins were not uncommon among local British woodworkers. Of the sixteen documented British cabinetmakers present in Charleston between 1790 and 1820, nearly two-thirds were from Scotland. The presence of Scottish artisans in the South was certainly not new, but the deterioration of Scotland's economy during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries resulted in a dramatic increase in emigration. Until about 1790, wages for Scottish craftsmen had exceeded or kept pace with the rising cost of food and other necessities in Scottish ports, but after that date inflation made it difficult for Scottish "mechanicks" to maintain the living standards of the previous generation. Numbers of those discontented individuals sought better opportunities in Britain's former colonies, including South Carolina, and Lee may have been among them.

Charleston's Scottish cabinetmakers were successful by period standards and most remained in business for fifteen years or longer. Although Lee's career was cut short by his untimely death at age thirty-four, he apparently shared in their success. Lee owned two or more slaves, one of whom may have worked in his shop. Business was so brisk that he could offer employment to two journeymen cabinetmakers in 1810. Accounts with another artisan show that Lee purchased substantial amounts of furniture hardware, including dozens of locks and bed bolts, sets of coffin furniture, table hinges, and quadrant hinges like those on the secretary drawer in this press. These purchases substantiate the range of forms produced in Lee's shop.

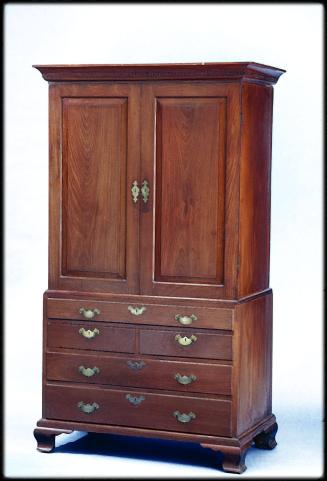

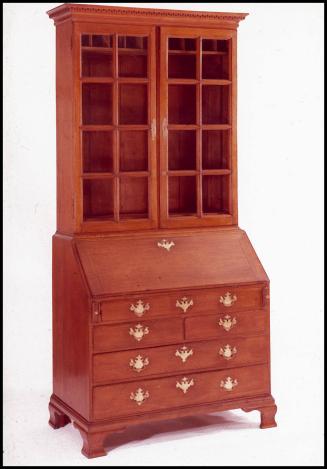

The clothespress Lee built for the prominent Ball family is similar to other Charleston-made examples in several ways. Although unusually conservative in style, its great height (nearly eight feet) and the inclusion of a secretary drawer are typical of many Charleston presses of the early national period. Nearly all of the city's clothespresses date from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Previously, the double chest of drawers was the most prevalent of the large case forms used for storing textiles. However, British householders began abandoning the double chest in favor of the clothespress during the last quarter of the eighteenth century and newly independent Charlestonians readily followed their lead, just as they had done for generations before.

InscribedThere is an illegible pencil inscription on the top of the upper case. "Grimball / Cabinit maker / Charleston" is penciled inside the bottom of the upper case. The last three words may be by a different hand. "Bott" [possibly Bottom] and "Thomas Lee" are penciled on the bottom of the lower case.

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceThe first owners of the press were the wealthy South Carolina planter John Ball, Jr. (1782-1834), and his first wife, Elizabeth Bryan Ball (1784-1812), who may have used it at their Charleston residence or at nearby Comingtee plantation. It descended to their daughter, Lydia Jane Ball (1807-1841); to her daughter, Ann Simons Waring (1831-1905); to her son, Dr. Edmund Waring Simons (1867-1940); to his daughter, Lydia Jane Simons (b. 1907); to her heir, who sold it to Estate Antiques in 1992. CWF acquired the press from Jim and Harriet Pratt, Estate Antiques, the same year, together with the Ball family Bible.

Exhibition(s)

Ca. 1810

1805 (dated)

1821

ca. 1775

1800-1815

1760-1780

1765-1780

1795 (documented)

ca. 1775

1760-1780

1805-1815

1797-1800