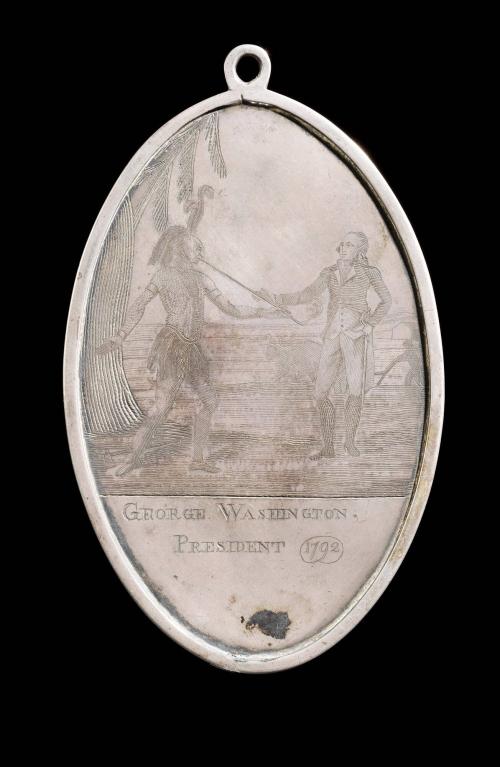

George Washington Indian Peace Medal (small size)

Date1792

Maker

Unidentified

MediumSilver and silver solder

DimensionsHeight: 5 1/4" Width: 3 3/16" Weight: 76.15 grams (1175 grains)

Credit LineMuseum Purchase, Lasser Numismatics Fund

Object number2021-6

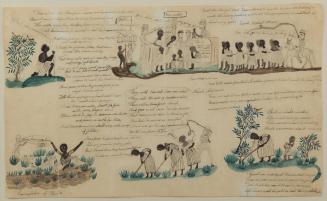

DescriptionOval-format medal composed of an engraved plate set within a rectangular-sectioned bezel and mounted with a similar suspension loop at the top. All three elements are joined by silver solder, visible where they meet at 12:00.The obverse is engraved with a scene of President Washington, in military uniform, sharing a Peace Pipe with a traditionally-clad Native American warrior who has just placed his tomahawk on the ground behind him. While Washington stands in front of a farming scene, the warrior stands below three branches of a large tree.

An early rendering of the Great Seal of the United States is engraved on the reverse.

Label TextIn April of 1789, when George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States, the nation’s leaders were well aware of the vital impact “peace medals” had as diplomatic gifts to American Indian leaders. The phenomenon began decades earlier with the distribution of British-made brass medals crafted specifically to appeal to the “Indian trade.”

By the French and Indian War, the Anglo-American colonists began producing larger and more impressive medals intended to compete against varied European interests for the allegiance of diverse Native American groups. These include Quaker-commissioned medals struck in Philadelphia for 1757’s Treaty of Easton, Sir William Johnson’s awards for the 1760 taking of Montreal, and New York’s “Happy While United” medals of the mid-1760s. With the Revolutionary War came others engraved in Boston for the Treaty of Watertown, signed with the Mi’kmaq in 1776, and Virginia’s “Happy While United” medals cast in 1780 for presentation to the Commonwealth’s Indian allies.

Those in the newly formed War Department, responsible for overseeing Indian affairs, faced some challenges in procuring these indispensable silver medals. With the U.S. Mint and mechanical production still years away, there was only one avenue to make the large, high quality medals required to convey the importance these honors embodied. Each had to be wrought by an accomplished silversmith and painstakingly engraved by an expert hand. It was time consuming and expensive, but well worth it to the Government, and heartily appreciated by the recipient.

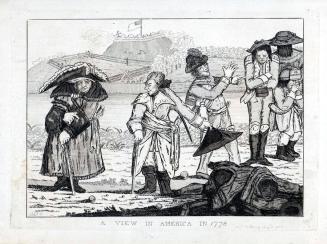

1789 also saw the Nation’s initial production of Indian peace medals, which were very large, oval, and engraved with the legend G. WASHINGTON PRESIDENT. Known from a single likely-authentic example, it carries a scene of the goddess “America,” in the guise of Minerva, passing a pipe to a Native warrior. With her shield and spear on the ground and the warrior’s tomahawk falling from his hand, its message of peace is clear. On the reverse appears the Great Seal of the United States. Though unproven, it is thought these medals were distributed to Creek recipients at the signing of the Treaty of New York in 1790.

A more spectacular design superseded the premier type in 1792. These new medals began the convention of including a prominent image of the sitting President on the front. The tradition continued for 99 years, until the end of the Indian peace medal program in 1891.

Also very large and oval, they present a view of George Washington helping to support a pipe being smoked by a traditionally-clad Native American warrior. On equal footings, the President appears in his military uniform while his ally wears armbands, a feathered headdress, and a large oval medal around his neck. Behind the warrior rests his tomahawk, just placed on the ground. This spectacle of a peace ceremony occurs at the edge of wood, with the warrior below the branches of a tree and Washington before an agricultural scene. Below is the legend GEORGE WASHINGTON, PRESIDENT 1792, in exergue. Its reverse carries a beautiful engraving of the Great Seal, much like that seen on the earlier medal.

Being official gifts of the United States, these resplendent pieces were seen as supreme emblems of importance and position by both parties. They were made in three sizes and given according to the rank of the accepting Chief. Bestowed with great pomp and ceremony, each medal was accompanied by a certificate which spelled out the credentials of the holder and the requirements of deference and respect owed to him by others. At the time, these esteemed American Indian leaders were often referred to as Grand Medal Chiefs.

Only made in 1792, 1793, and 1795, those of the first two years with the “7” looping around the whole of the date are the most finely engraved. With one exception the 1792 medals are unsigned, though some from the later years carry the mark of Philadelphia silversmith Joseph Richardson, Jr. (others bear similar punches for a pair of yet-identified makers). Since Philadelphia was the nation’s Capital at the time, the peace medals were apparently supplied to the War Department by numerous local artisans, though we don’t know who all of the makers were, or how many were made.

During the early 1790s, the policies and actions of the United States, as relating to American Indians and the territories controlled by European interests, were extremely complicated and fluid. President Washington sought to forget the hostilities of the Revolution and dedicated considerable effort and expense to establish peace with the Southern tribes out of the great principles of Justice and humanity, to use his words.

Charged with a number of ambassadorial goals, a Cherokee delegation arrived in Philadelphia in January of 1792. Not seeking to treat with the United States on behalf of their tribe alone, they also spoke officially for the Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws. These diplomats were looking to settle some territorial issues and receive the agricultural and husbandry-related equipment promised to them under the Treaty of Holston, signed the previous July.

In response, Secretary of War Henry Knox directed that the Cherokee delegation shall;

"….be liberally supplied with presents, as well as suits of clothing for themselves and families, and of distinctive silver Medals – and that particular presents shall be sent forward by the Agent to the little-Turkey (principal Chief of the Cherokee), and the other principal Chiefs remaining at home. That besides which, Twenty more suits of clothing, and setts of Medals be entrusted to the Agent in order to distribute among the principal Chiefs of the Chickasaws and Choctaws."

Knox’s order shows that the primary recipients of the 1792 peace medals were from Southern Native American tribes, and there is solid evidence they had the desired effect of inspiring allegiance to the United States. It came in the form of a protest from Spanish-held Louisiana and West Florida, lodged after one of the medals into the hands of Baron de Carondelet, Governor of the territories. According to his emissaries, by distributing silver medals which they described as those which the US have distributed with the effigy of the president, and at the bottom, George Washington President 1792, the United States was guilty of meddling in Spanish colonial affairs. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, clearly unmoved, addressed their grievances as a courtesy, but took no action to halt the distribution of medals to the nation’s Native allies.

In addition to the dozens of 1792 medals that went to the Cherokees, Chickasaws, and Choctaws, at least two went to leaders of a Northern tribe. Also visiting Philadelphia that year were a pair of Seneca Chiefs from New York, Red Jacket and Farmer’s Brother. Of the highest rank, Red Jacket received a medal of the large size, while Farmer’s Brother got one of the small size, both believed to have been presented by Washington at the President’s House on Market Street. Remarkably, both medals survive in museum collections in upstate New York. If that isn’t amazing enough, Red Jacket lived until 1830 and was portrayed a number of times wearing his medal. Farmer’s Brother’s example is just like Colonial Williamsburg’s medal, though it looks to have been engraved by a different artisan.

Production of the large format oval medals ended in 1795, likely because of the expense and difficulty of having them hand-made, perhaps compounded by an increasing need for them. Still with no means to have them die-stuck in the United States, the government turned to Boulton & Watt’s private mint in Birmingham, England in 1796 for a new series of three medals. Much smaller and nowhere near as impressive, these less successful Indian peace medals bear images of humble domestic scenes. Today, the trio are known as the “Seasons Medals.”

Of paramount historical significance and the highest rarity, most of the authentic engraved Indian Peace medals of George Washington’s presidency are found in institutional collections. Perhaps a dozen of the 1792 medals, being of the initial year of issue and awarded primarily to Southern Chiefs, are known. One of the six or so of the smaller size currently recorded, Colonial Williamsburg’s example is amongst the finest, and has resided in famous American medal collections since the early 20th century.

InscribedObverse engraved GEORGE WASHINGTON , PRESIDENT 1792 in two lines below the exergual line.

ProvenanceEx coll: F.C.C. Boyd; John J. Ford, Jr. (Stack's, May 2004, lot 190); Donald G. Partrick (Heritage, January 2021, lot 3964).

ca. 1840-1850

ca. 1805

1800-1827 (compiled); some 1726

1750-1770

ca. 1800

Probably 1832-1835

August 1, 1778