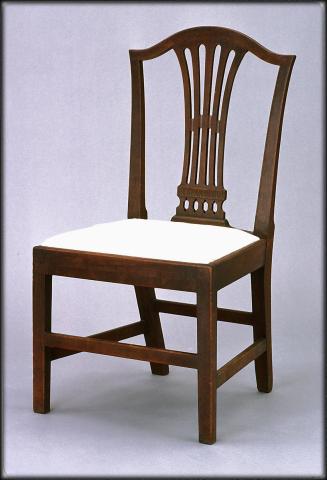

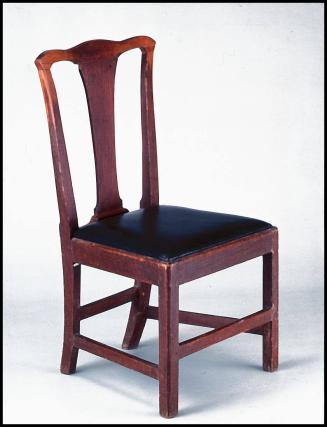

Side Chair

Date1845-1855

Attributed to

Thomas Day

MediumMahogany, yellow pine, tulip poplar, linen, and curled horsehair

DimensionsOverall: 31 1/4 × 18 1/8 × 20 1/4 × 16in. (79.4 × 46 × 51.4 × 40.6cm)

Credit LineGift of Ronald L. and Mary Jean Hurst in Honor of Leroy Graves

Object number2022-71

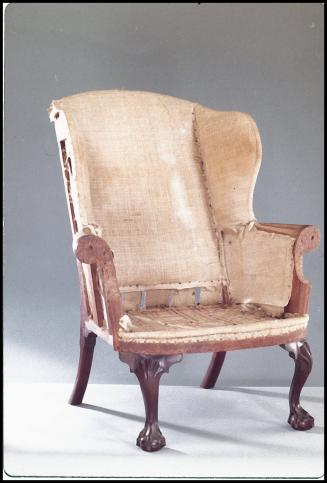

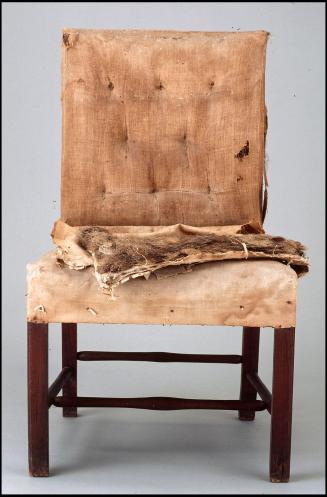

DescriptionShaped and curved crest rail with rounded ends and suggestions of C scrolls and lobes along top and bottom edges, carved on top center with abbreviated foliate veins, overlaps and extends past stiles; shaped and curved slat or stay rail tenoned between stiles; trapezoidal upholstered slipseat fits between rounded side seat rails that continue from stiles and is screwed from below to front and rear seat rails; bowed front seat rail has veneered rounded front edge with scalloped skirt; front curving squared and tapered cabriole legs; raking tapered rear legs; stiles and legs mahogany; all other elements mahogany veneered on yellow pine; tulip poplar slipseat frame. Slipseat survives with original linen two-colored webbing, bottom and top linen, and curled horsehair. Red wash or stain on top linen and slides of slipseat frame.Label TextThomas Day is the most renowned Black cabinetmaker of the 19th century. Born in 1801 to free Black parents, John and Mourning Stewart Day, Thomas was educated at a local school in southeastern Virginia and learned the art and mystery of cabinetmaking from his father. Around 1823, Thomas moved his shop from Hillsborough to Milton, North Carolina and over the years became an incredibly successful businessman producing furniture and architectural woodwork for North Carolina homes until his death in 1861.

Day managed to navigate being a free person of color in ante-bellum North Carolina. When sixty-one white citizens of Milton and Caswell County petitioned the North Carolina General Assembly for Thomas' wife Aquilla Wilson Day, a free black woman, to be allowed to move to North Carolina in 1830, Day was described as a "cabinet maker by trade, a first rate workman, a remarkably sober, steady and industrious man, a highminded, good, and valuable citizen, possessing a handsome property in this town." Day was a slaveowner like many of these petitioners. But unlike them, Day appears to have quietly harbored abolitionist sentiments, attending The Fifth Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Colour in Philadelphia in 1835. The sixty-one white citizens were Day's customers, neighbors, and fellow parishioners. One such individual was Samuel Watkins, from whom Day purchased a brick tavern building on Main street in Milton in 1848 that became his shop and home. This chair may have been purchased by Samuel and Elizabeth Watkins for their neighboring home around 1850 as it descended to their great-granddaughter.

Day's furniture followed fashionable designs of the period popular in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, but with his own distinctive style. Based on his surviving work, he appears to have been familiar with John Hall's THE CABINET MAKERS’ ASSISTANT published in Baltimore, Maryland in 1840. Indeed this chair displays elements related to fig. 146 in that design book but with the scrollwork and flourishes that Day is known for today. In the 1850s, Day introduced mechanization to his shop, purchasing a steam engine and belt-driven woodworking machines. These allowed Day's workmen to increase production of furniture and woodwork that would be finished in "fine mechanical stile."

This chair survives with its original upholstery foundation. The reproduction claret colored silk velvet on the seat was selected based on surviving silk threads discovered under a nail on the seat and was applied non-intrusively over the original foundation. Red and even purple velvets were popular choices in the 1840s and 1850s for seating furniture. A set of chairs produced in New York by Charles Baudouine for James Polk's White House in c.1845 were upholstered in purple velvet. Thomas Day is also known to have upholstered chairs in a simpler black haircloth.

MarkingsMarked VI on slipseat an IV on top of chair front seat rail.

ProvenanceBarbara Allen Watkins Blanton stated that this chair had descended in the Watkins family of Milton, North Carolina to her. The chairs may have originally been owned by her great-grandparents, Samuel Watkins (1800-1868) and Elizabeth Stamps Watkins (1813-1896) of Milton, North Carolina and passed through their offspring to her. But it is also possible that they came into the Watkins family through the marriage of Glenn Garland Donoho (1867-1945) and Emily H. Watkins (1873-1959). Glenn G. Donoho’s parents Thomas A. Donoho (1827-1887) and Isabella Glenn Garland Donoho (1832-1886) lived at Longwood Plantation just outside Milton.

Ca. 1730

1750-1770

1780-1790

ca. 1790

ca. 1765

1805-1815

1766-1777

1815-1825

1790-1810

ca. 1810

1760-1785

1780-1800