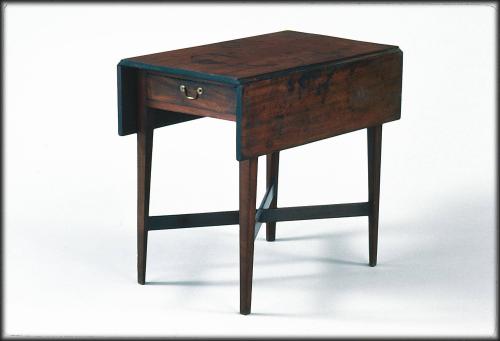

Pembroke table

Date1790-1815

MediumMahogany, maple (by microanalysis), white pine (by microanalysis), and tulip poplar.

DimensionsOH: 28" OW(closed): 17 7/8" OW(open): 35 1/4" OD: 31 1/4

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1966-477

DescriptionAppearance: breakfast table with rectangular top, single drawer, and two drop leaves; cross stretchers; four straight tapered legs.Construction: The cross stretchers are half-lapped at the center, with the upper stretcher carved at the intersection to suggest a mitered joint. Traditional mortise-and-tenon joinery appears on the frame, although the drawer blades are double-tenoned into the legs. The inner rails are wrought-nailed to the fixed hinge rails. Finger joints are used on the leaf supports, which are deeply chamfered on the undersides to create finger grips. The drawer moves on runners wrought-nailed into the inner rails. A pair of drawer stops are nailed to the inner rails in a similar manner. The drawer bottom is chamfered on the underside, set into grooves on the front and sides, and flush-nailed at the rear.

Materials: Mahogany top, leaves, drawer front, end rails, legs, and stretchers; maple (microanalysis) hinge rails; white pine (microanalysis) inner rails, runners, drawer stops, and drawer bottom; tulip poplar drawer sides and drawer back.

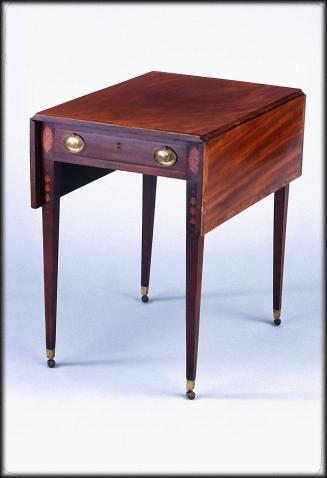

Label TextNeoclassicism emerged as the prevalent furniture style in Europe during the 1770s. Over the next two decades, the fashion made its way to America and was readily accepted in major southern furniture-making centers such as Baltimore, Norfolk, and Charleston. Artisans and patrons in smaller southern towns, particularly those in the Virginia and North Carolina Piedmont, were not so eager to adopt the new taste. Instead, many held fast to designs rooted in the earlier neat and plain tradition. Contributing to this stylistic conservatism was the delayed inland development of specialized woodworking trades like inlay making and veneer cutting, both essential to the production of full-blown neoclassical cabinet wares.

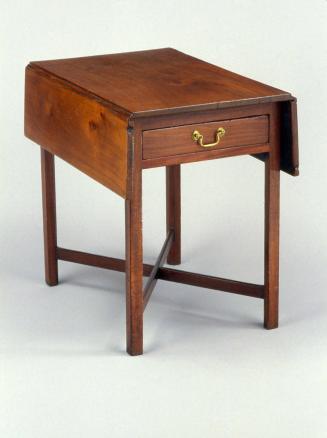

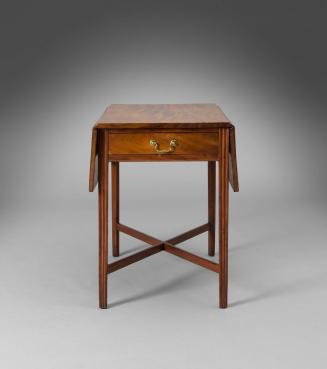

Few towns clung more tenaciously to the earlier style than Petersburg, Virginia, where postwar economic retrenchment reduced coastal and international trade ties, thus limiting importation of the latest European wares. Nearly a dozen pieces of Petersburg furniture now in the CWF collection confirm this lingering interest in the plain style (see acc. nos. 1992-86 and 1990-202). A similar trend occurred in many of the rural regions for which Petersburg served as the primary market center, including the Roanoke River basin of North Carolina, where this mahogany breakfast table was made. Although its dramatically tapered legs indicate an awareness of the neoclassical taste, the simple overall form, crossed stretchers, bail-and-rosette drawer pull, and minimal ornamentation all recall the earlier neat and plain style.

Several tables discovered during field research by MESDA can be attributed to the same Roanoke basin artisan who produced the CWF table. His shop was probably located in the Franklin County town of Louisburg, where the present table was found. A second, virtually identical table also has a long history of ownership in Louisburg (MESDA research file 12,095). Among the distinguishing characteristics of the group are shaped drawer stops, tulip poplar drawer construction, and maple and white pine framing. The tables also feature large vertical glue blocks on their interior corners, triangular chamfering on the lower edges of their swing hinge rails, and similarly dovetailed drawers with chamfered bottom panels set in grooves.

Evidence of Petersburg's influence in the upper Roanoke basin is seen in the existence of several Petersburg breakfast tables that are similar to the North Carolina models. This influence may have arrived in the form of imported cabinet wares since it is well documented that a number of early Roanoke basin residents owned Petersburg furniture. Records also reveal that many Petersburg cabinetmakers unable to compete with the growing importation of northern furniture migrated into North Carolina during the early nineteenth century. Eleven relocated to the upper Roanoke basin between 1790 and 1820.

One migrant was Lewis Layssard (w. ca. 1814-ca. 1833), who had direct ties to Louisburg. Layssard and his partner, John Lorrain, operated a shop in Petersburg that specialized in making and repairing "LOOKING-GLASSES of all descriptions, sizes and qualities." The partnership was short lived, and the multitalented Layssard subsequently opened a blacksmith shop. By December 1817, he moved to Louisburg, where he resumed the cabinetmaking trade. Layssard advertised that he had in his employ skilled artisans from both Petersburg and New York who were capable of building "all kinds of furniture, as good as any of the Northern Towns." Despite such notices, it is apparent that Layssard and other craftsmen in the upper Roanoke basin confined their efforts to making furniture in a more basic style.

InscribedNone

MarkingsNone

ProvenanceThe table was purchased in 1966 from Williamsburg antiques dealer William Bozarth, who had acquired it from a family in Louisburg, N. C.

ca. 1775

1790-1800

1755-1770

1775-1790

Ca. 1770

1800-1815

c. 1790

ca. 1790

Ca. 1725

ca. 1775

1735-1750

1700-1730