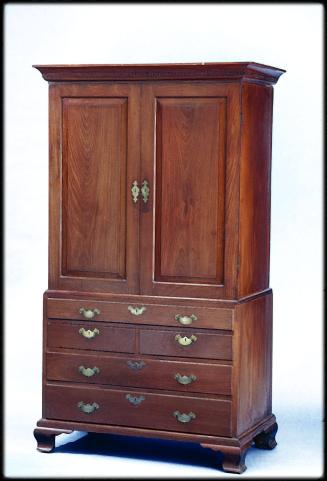

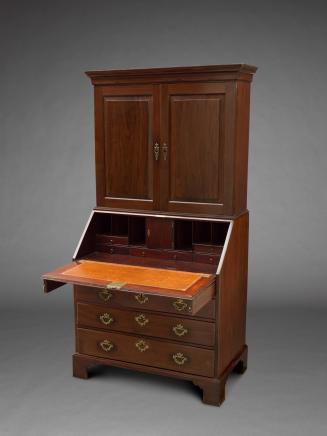

Clothespress

Date1795 (documented)

Artist/Maker

Rookesby Roberts

(b.1765)

MediumBlack walnut (by microanalysis) and yellow pine

DimensionsOH: 76 1/2" OW: 45 1/2" OD: 20 3/4"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1979-5

DescriptionAppearance: Four straight bracket feet; base molding; two full-width drawers with scratch beaded edges, cast brass oval drawer pulls with top-mounted oval rings, and inset brass escutcheons; two-part waist molding; two flat-paneled doors concealing three sliding trays with shaped sides and unmolded front rails; molded projecting cornice. Construction: The removable cornice is built around a dovetailed frame that has a medial rail and quarter-round vertical glue blocks at the outer corners. A black walnut molding is applied to a yellow pine backing that is triangular in cross section.

The carcass of the upper case is dovetailed in the usual fashion. A series of widely spaced blocks glued to the top board keep the removable cornice in place. The back consists of three vertical raised panels within a pinned mortised-and-tenoned frame, the whole set into rabbets on the case sides, set flush at the top and bottom, and attached with hand-headed cut nails. The door panels, flat on the front and deeply beveled on the reverse, rest in frames assembled with double-wedged through-tenons. Dadoes cut into the inner surfaces of the case sides accept three sliding trays. The trays are dovetailed at the corners and have bottoms that are flush-nailed to the frames. These bottom boards project beyond the tray sides to slide in the dadoed case sides. The topmost element of the waist molding is attached to a series of close-set blocks glued to the bottom of the upper case.

The dovetailed lower case has full-thickness dustboards that extend to half the case depth and are backed by drawer runners set in the same dadoes. A pair of butted horizontal backboards is attached in the same way as the back of the upper case. The squared lower element of the waist molding is attached to the top of the lower case and is backed by widely spaced glue blocks that also act as plinths for the upper case. The base molding is backed by close-set glue blocks that extend along the front and sides of the case bottom and extend in along the rear edge about twelve inches from each side. Blind dovetails join the bracket feet, which are backed by stacked, horizontally grained blocks set between shaped flanking blocks.

The dovetailed drawers have beveled bottoms set into grooves at the front and sides and are nailed along the rear edge. The bottom panels are supported by close-set glue blocks placed along the front and sides. The rear block on each side is mitered to prevent the drawer from dragging when it is pushed into the case.

Materials: Black walnut (by microanalysis) case sides, doors, drawer fronts, drawer blades, cornice, waist molding, base molding, and exposed parts of feet; all other elements of yellow pine.

Label TextThis black walnut clothespress is one of the few pieces of furniture whose production can be confidently ascribed to Williamsburg, Virginia, after the Revolution. It was made in 1795 for St. George Tucker (1752-1827), a prominent jurist who greatly expanded his Williamsburg house in the late eighteenth century and continued to buy furniture to fill its many rooms until the 1820s. Tucker's accounts demonstrate that while some of his cabinet wares were imported from Norfolk, Philadelphia, and New York, he also patronized Williamsburg artisans, mainly for bedsteads and large case pieces, which were more cumbersome to ship. Among Tucker's many local acquisitions were several "presses," clothespresses, and "Wardrobes," but only one matches the description of the CWF clothespress. Billed as "a walnut Clothpress" [sic], Williamsburg cabinetmaker Rookesby Roberts sold it to Tucker for £8 on June 1, 1795 (original receipt in the Tucker-Coleman papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary).

Twenty-nine-year-old Roberts had made furniture in his own right for less than two years, and his name disappeared from local records only a year later. However, his background and professional associations suggest that Roberts was the product of long-standing Williamsburg cabinetmaking practices. Born to a local family in 1765, he was almost certainly trained in Williamsburg during or just after the Revolution, possibly by cabinetmaker Richard Booker (b. ca. 1752) for whom he apparently worked as a journeyman from at least 1789 until Booker died in late 1793. Booker, in turn, had participated in the city's cabinet trade continuously since the completion of his training about 1773. Also a member of a long-settled local family, Booker likely was trained in Williamsburg as well.

Roberts's strong ties to earlier Williamsburg furniture-making traditions explain the conservative appearance and construction of the clothespress he made for Tucker. Except for its original neoclassical brasses and attenuated moldings, there is little stylistic difference between the Tucker press and examples made in Williamsburg several decades earlier. The British-inspired two-door format was commonly employed in most Tidewater cities as early as the 1750s. Structural elements follow the same pattern, as evidenced by a comparison of the paneled back and the horizontally grained foot blocking employed on the Tucker press and those on a black walnut clothespress made in Williamsburg about 1770 (CWF acc. 1950-351). Only the extensive use of original hand-headed cut nails confirms that the Tucker press was produced after the Revolution. Such nails, with shanks cut by machine from rolled sheet iron, were not generally available in America until the 1790s.

A privately owned bookpress that also descended in Tucker's family and remained in his house until 1994 is the only other known example of Roberts's work (see object file for image). Although its molding profiles differ from those of the clothespress, both objects exhibit the same dovetailing patterns, and their drawer bottoms are secured with rows of identical close-set glue blocks mitered at the rear corners. The doors on each piece are joined with double-wedged through-tenons and feature the same hinge placement. Both case backs consist of vertically oriented, sharply beveled panels that project beyond the surface of the frames in which they rest. Even the nails used to attach the back assemblies are set in the same configuration. Unfortunately, there is no record of a payment from Tucker to Roberts for a bookpress.

Other aspects of Roberts's career are known only through the Tucker family papers. In addition to making new furniture, Roberts apparently carried on a brisk repair business. In the two-year period beginning January 1794, he altered or repaired at least eighteen pieces of furniture for Tucker, including everything from looking glasses to bedsteads. Like most of his colleagues, Roberts also made coffins, two of which he supplied to the Tuckers. None of these activities seems to have been highly profitable. Roberts's earnings for repairing and altering Tucker's furniture rarely amounted to more than a few shillings per project. The coffins brought about £2 each.

Roberts disappeared from Williamsburg records after 1796, and it is likely that he followed the lead of other local artisans and left in search of a more lucrative situation. Without a major port, Williamsburg's economy had always been dependent on the presence of the colonial government, and when the state moved its seat to Richmond in 1780, Williamsburg was economically crippled. The population fell from more that 1,800 to just 1,344 individuals by 1790, nearly half of whom were enslaved. Meanwhile, just as the in-town market was evaporating, opportunities for exporting Williamsburg-made furniture to the surrounding countryside vanished in the face of competition from the much bigger cities of Norfolk and Richmond. Even in large urban centers, southern cabinetmakers were finding it difficult to compete with the huge northern shops that produced volumes of inexpensive but fashionable neoclassical furniture and shipped it south as venture cargo. In the end, few of Williamsburg's postwar cabinetmakers were able to remain in business for more than three years.

InscribedA circa 1900 paper label pasted inside the back of the lower case is inscribed in ink: "This Press was the property of Judge St. George Tucker and Frances Bland his wife of Cawsons- Then of Daug[hter?] Mrs. Frances Bland Coalter[,] her Son St. George Tucker Coalter[,] then his Daughter Mrs. Virginia Coalter Braxton of Stanley [dates to?] Tucker to about 1756."

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceThe clothespress was first owned by St. George Tucker (1752-1827) and, contrary to the statement on the attached label, his second wife, Lelia Skipwith Carter Tucker (b. 1767), who were married in 1791 and resided in Williamsburg until their deaths. It descended to St. George Tucker's grandson from his first marriage, St. George Tucker Coalter (son of the Frances Bland Coalter mentioned in the label) and his wife, Judith Tomlin; to their daughter, Virginia Coalter Braxton of Stanley plantation, Hanover Co., Va. The press then descended through the Tomlin family of Hanover Co. to Judith Tomlin Alexander, from whom it was acquired by antiques dealer H. Marshall Goodman, Jr., around 1978. Goodman sold the press to CWF the following year.

Exhibition(s)

1804-1813

1805 (dated)

1760-1780

ca. 1775

Ca. 1810

1765-1775

1770-1785

1805-1815

ca. 1740

1805-1810

1800-1815

1760-1775