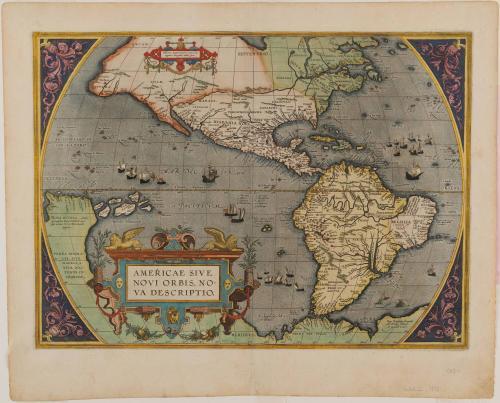

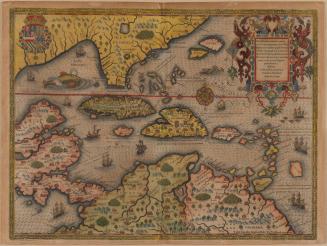

AMERICAE SIVE/ NOVI ORBIS, NO=/ VA DESCRIPTIO.

Date1592 (originally published 1587)

Cartographer

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

After work by

Gerard Mercator

(1512 - 1594)

Printer

Christopher Plantin

(1514 - 1589)

Publisher

Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598)

MediumBlack and white line engraving with period hand color on laid paper

DimensionsOH: 13 7/8" x OW: 19 1/8"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1986-81

DescriptionThe lower left cartouche reads: "AMERICAE SIVE/ NOVI ORBIS, NO=/ VA DESCRIPTIO."The lower right corner of the map reads: "Cum Priuilegio decennali/ Ab. Ortelius delineab./ et excudeb 1587"

Label TextAbraham Ortelius is considered one of the most influential figures in the history of modern cartography. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, originally published in 1570, is generally regarded as the first modern atlas because Ortelius based his information on contemporary charts and maps. To produce it, he assembled the most accurate works of eighty-seven cartographers, all of whom he acknowledged in the atlas, a rather uncharacteristic gesture for sixteenth-century cartographers. Descriptive text accompanied each map.

Ortelius continually updated the maps and geographical information in subsequent editions of the Theatrum, which remained popular throughout the sixteenth century. In fact, the demand was so great that during the forty-two years the atlas remained in print, no fewer than thirty-four Latin editions were published, followed by editions in Dutch, German, French, Spanish, English, and Italian.1

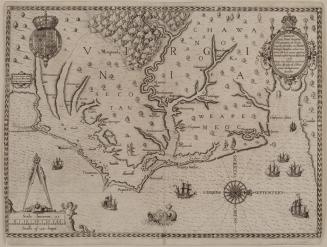

Early editions of the Theatrum included only one map devoted solely to the Americas, Americae Sive Novi Orbis. Largely derived from Gerardus Mercator's twenty-one-sheet world map published in 1569, it was reengraved three times during the life of the atlas. The first two maps bearing this title appeared in editions from 1570 to 1587. The most noteworthy feature was the geographical misrepresentation of the west coast of South America, which showed a large bulge protruding into the Pacific Ocean. (fig. 44) This distortion appeared frequently on maps throughout the sixteenth century.2 In the new plate Ortelius engraved in 1587 (this copy), he corrected the distortion and illustrated "Chili" not as simply a town but as the entire region encompassing the southwest coastline.

The most important change in the 1587 version was the inclusion of a body of water, or inlet, that may be the first illustration of the Chesapeake Bay on a printed map.3 (figs. 46 and 47) This finger of water, which flows due west, is depicted directly below Apalchen and above Wingan Dekoa. Arthur Barlowe, who explored the area during Sir Walter Ralegh's 1584 expedition, identified "Wingandacoa" as the land inhabited by Native Americans under the rule of King Wingina. In the narrative of the voyage, Barlowe wrote, "The king is called Wingina, the countrey Wingandacoa, (and nowe by her Majestie, Virginia)."4

These first English colonists investigated the area around the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay in 1584 and 1585 where they found more fertile land and deeper harbors and channels around Wingandacoa than at Roanoke Island. Their favorable recommendations influenced Ralegh's decision to locate the Virginia colony on the Chesapeake rather than in North Carolina.

Just how Ortelius acquired knowledge of Wingandacoa is unclear. Richard Hakluyt, one of Ralegh's directors in the Virginia experiment, published Barlowe's account of the 1584 Virginia expedition in 1588, the year after Ortelius's map was engraved with Wingan Dekoa and the body of water thought to be the Chesapeake Bay. Perhaps Hakluyt shared Barlowe's manuscript with Ortelius prior to its publication because they had been corresponding since their initial meeting in England in 1577.5 A 1587 letter from Hakluyt to Ralegh documents that he consulted Ortelius's earlier rendering of Virginia.6 Given the opportunity, Hakluyt would likely have suggested to Ortelius that he include the Chesapeake Bay on his map.

1. Upon Ortelius's death in 1598, the map plates were sold to J. B. Vrients, who continued to print from them. By 1612, the year of Vrients's death, competition made Ortelius's atlas unprofitable and publication ceased.

2. For a discussion of the distortions in early representations of South America, see Uta Lindgren, "Trial and Error in the Mapping of America during the Early Modern Period," in Hans Wolff, ed., America: Early Maps of the New World (Munich, 1992), pp. 145-160.

3. Bob Augustyn was the first to call my attention to this feature. This theory was subsequently discussed in Burden, Mapping of North America, p. 79.

4. David B. Quinn and Alison M. Quinn, eds., Virginia Voyages from Hakluyt (London, 1973), p. 4.

5. George Bruner Parks, Richard Hakluyt and the English Voyages, ed. James A. Williamson (New York, 1928), p. 62.

6. Quinn and Quinn, eds., Virginia Voyages, p. 91.

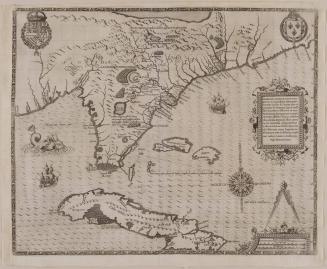

May 1587

First published 1606; This example: 1634

1795-1822

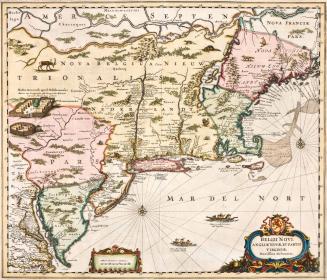

ca. 1684; originally published ca. 1655