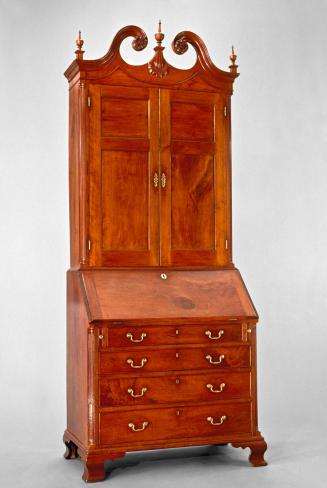

Desk

Date1795-1805

Attributed to

John Shearer

MediumBlack walnut, yellow pine, and tulip poplar.

DimensionsOH:48" OW: 44" OD: 22"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1990-88

DescriptionAppearance: Standard slant top desk form with the following notations: four graduated large drawers feature large recessed serpentine panel; very large quarter columns have stop fluting that ends in a concave arc; capitals of quarter columns feature carved swags on a punchwork ground; case sits on four very large ball-and-claw feet with large flanking blocks; fall board inlaid with lightwood swags; architectural interior features six fluted document drawers (one non-functional) supporting one long top drawer that consists of seven carved masonry arches with keystones; tambour prospect door features simulated hinges; prospect opens to reveal three small drawers inlaid with swags; prospect carcass pulls forward to reveal four "secret" drawers with leather pulls; flanking prospect are two banks of three letter compartments with serpentine dividers over two serpentine drawers over one swag-inlaid serpentine drawer. Construction: The top board is blind-mitered dovetailed to the case sides. The horizontal backboards are nailed into rabbets at the top and sides and flush-nailed at the bottom. Cock beading surrounds the opening for each fall-board support. Traditional grooved and mitered batten construction, additionally secured with pins, is used on the inlay-decorated fall board that has a leather writing surface. The interior desk surface, which consists of a walnut board butt-joined to a yellow pine board below the prospect section, appears to be attached to the case sides with a sliding full or half-dovetail. A three-sixteenths-inch-high platform sits below the interior drawers. The drawers have one-piece fronts that are conventionally dovetailed together with bottom panels nailed into rabbets at the front and sides and flush-nailed at the rear. A similarly joined full-width upper drawer with an architectonically carved single-board front sits on the top board of the prospect section. It is flanked on either side by small thin drawers. The drawered prospect section has beaded dividers that fit in either squared or mitered slots. Four document drawers with engaged half-column facades have decoratively sawn upper edges on their side panels. The sides are nailed into rabbets at the front and flushed-nailed on the bottom and at the rear. An additional document drawer with a pilastered facade sits to the right of the central prospect door, while the pilaster on the left is fixed. These tall drawers track on thin runners nailed onto the concealed part of the interior writing surface. A canvas-backed tambour door, deceptively adorned with inoperative brass hinges, slides open to reveal a removable compartment that has open dovetail and rabbeted divider construction. Consisting of two vertically placed rectangular drawers over a single horizontally placed rectangular drawer on which the rear upper edge of the front board is rabbeted and fitted into a corresponding rabbet on the blade, this compartment slides out to reveal four hidden stacked drawers with leather pulls.

The quarter-columns on both sides of the case are nailed to the case side and to a vertical stile nailed in place above and below. The one-piece cock-beaded stiles that abut the fall-board supports are nailed into shallow dadoes, and the cock-beaded drawer blades are similarly joined to the vertical stiles to which the cock beading is applied. Mortise-and-tenon drawer supports on the rear of these approximately one-quarter-depth blades are set into either full or half-dovetailed dadoes in the case sides. Nailed on top of these supports are thin drawer guides. Completing each frame is a mortise-and-tenon member that spans the rear of the case. Relatively coarse double- or triple-laminated drawer stops are nailed to the inside of the backboards. The bottom drawer sits on three-sixteenths-inch runners nailed to the bottom board of the desk, which is apparently dovetailed to the lower edges of the case sides. The coved upper part of the front base molding extends several inches inside of the case to form the bottom drawer blade. Nailed and screwed to the underside of this is the fillet portion of the base molding, which in turn extends about seven inches under the case and is mitered at the front corners, forming a frame to which the feet are attached. A pair of round or square dowels at the top of each of the single-board feet penetrates both the frame and the bottom board; the feet and separate knee-blocks are additionally secured with nails. Large iron L-brackets, now missing, once further held the feet to the case.

The drawers are conventionally joined although the serpentine fronts are sawn out of two-and-one-quarter-inch-deep boards, resulting in correspondingly deep dovetails. The bottom panels are beveled and set into grooves at the front and sides and flush-nailed at the rear.

Materials: Black walnut top, sides, fall board, fall-board supports, all drawer fronts, blades, stiles, quarter columns, exterior panels on prospect case, moldings and cock beading, desk dividers and shelves, and feet; yellow pine back, bottom, secondaries for all drawers, backboard on prospect case, rear part of writing surface, and drawer runners; tulip poplar drawer guides.

Label TextCabinetmaker John Shearer worked in the upper Potomac River valley, primarily in the town of Martinsburg, Virginia (now West Virginia), during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. CWF is fortunate in owning three pieces of his work: this massive black walnut desk, a signed cherry pier table (acc. 1980-7), and a signed and dated chest of drawers (acc. 1993-325). Today, Shearer is widely recognized among southern furniture enthusiasts as a prolific and creative artisan, but his highly individualistic style has prompted many modern observers to regard him as a rather peculiar craftsman. Like the Dunlap family of furniture makers in New Hampshire, Shearer is often characterized as a tradesman whose creations fall outside American cabinetmaking norms and whose imaginative designs reflect an aberrant craft vision. Yet such assessments ignore Shearer's ethnic origins and overlook the culturally vibrant area in which he worked. These analyses are based on an urban, Anglocentric standard of connoisseurship that pays little attention to the Scottish, Irish, Welsh, German, Swiss, and other ethnic craft conventions that are key to evaluating the material culture of the Virginia and Maryland frontiers. When considered in a more balanced cultural context, Shearer's wares emerge as the logical expressions of a Scottish-born furniture maker working in the ethnically diverse Shenandoah Valley, and they inform modern observers not only about the maker's personal trade practices but also about the needs and desires of patrons in the backcountry.

Like many other western Virginia and Maryland artisans, Shearer blended popular classically inspired furniture designs with his own ideas. A strong reliance on architectonic motifs evident in his prominent use of fluted quarter-columns and neoclassical swags reveals an understanding and acceptance of urban British design standards. Shearer's furniture also shows the hand of a skilled maker with formal training. Unfortunately, little is known about the artisan's early life and education beyond the fact that he came to America from Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1775. Research in the 1970s strongly suggested that he was the son of Archibald (1732-1800) and Sarah Prather Shearer (1739-1805), who owned several thousand acres of land in Berkeley Country, West Virginia, and across the Potomac River in Washington County, Maryland. Records further indicated that John Shearer, son of Archibald, died in 1810. The recent discovery of a signed Shearer desk dated 1816 leaves no doubt that cabinetmaker John Shearer was not the son of Archibald, although he may have been a kinsman.

Although Shearer's birth and age at the time of his 1775 immigration are not known, the fact that his earliest dated work was made in 1800 suggests that he trained in Virginia rather than Scotland. He may have apprenticed in the Berkeley County town of Martinsburg, an important regional marketplace for northwestern Virginia and present-day West Virginia. At least five professional cabinetmakers were active in Martinsburg by the 1790s; after 1800, the number grew considerably. Shearer marked several of his pieces "Made in Martinsburgh."

More than two dozen pieces of furniture are either signed by or firmly attributed to Shearer. All share the maker's distinctive proportional sensibilities; many also illustrate his bold and exuberant carving style. Shearer's furniture without question reflects the hand of an artisan with considerable passion and energy. So, too, does his frequent expression of loyalist sentiments that appear in word and image on many of his creations. Among the more common are "God Save the King," "Victory be Thine," and "From a Tory / Vive le Roy." The CWF chest of drawers has an inlaid panel with the British lion rampant topped by a banner reading "Britannia Rules / Rules the Main." The drawer below bears an inlaid thistle, an allusion to Shearer's Scottish heritage, which, according to oral tradition and a surviving family Bible, was also proudly recalled by other family members.

While Shearer's prominent depiction of Tory political beliefs sets him apart from most American cabinetmakers, the sentiments are certainly linked to his ethnic origin and the backcountry context in which he worked. Settlement in the western part of Virginia expanded dramatically after the middle of the eighteenth century. The vast majority of new settlers were rural British, German, and Swiss immigrants. Most settled in the backcountry where land was still available. Not surprisingly, profound social and cultural differences soon distinguished the residents of the coastal Chesapeake from those of the backcountry. Western residents developed a growing sense of mistrust of the centralized state government after the Revolution. During the 1780s, state lawmakers instituted higher taxes and enacted laws that restricted local government, which heightened the antagonism. Similar trends occurred in other states. The conflict climaxed in western Pennsylvania in 1794 when an army of "defenders of liberty" from several states, including Virginia, took part in the Whiskey Rebellion.

Shearer's extraordinary furniture and his strong political beliefs were influenced by his experience in western Virginia. His depiction of the "Federal Knot" on the CWF chest and pier table may allude to a popular backcountry perception of the new, rigidly ordered, seemingly ineffective, and hopelessly entangled Federal government. Shearer's allegiance to backcountry views is also evident in the decoration of a desk made in 1810 for Samuel Luckett of Mt. Phelia plantation in Loudoun County, Virginia. On the fall board is an inlaid eagle surmounted by a banner inscribed "Liberty," a motif now typically interpreted as an expression of nationalistic or patriotic pride. "Liberty" had a different and far more parochial meaning for residents of the backcountry where ideas about personal liberty and self-determination were the basis for rejecting centralized government. These concepts were well rooted in the Scottish, Irish, Welsh, and rural English immigrants who had felt similarly oppressed by English authorities in Great Britain.

Beyond any political implications, the CWF desk stands as one of Shearer's more ambitious and artistic efforts. Displaying an exuberant sense of baroque sculptural massing, it features a dramatic writing interior with rusticated arches and four document drawers faced with fluted pilasters. The prospect section consists of a tambour door with a pair of sham brass hinges and a small keyhole escutcheon. Some of the interior drawers are adorned with finely inlaid string swags draped over brass drawer pulls representing the cloak pins from which real drapery was suspended. The vaulted brackets above the pigeonholes are part of a full-width drawer front cut from a single board.

The exterior case is no less striking. Framing the carcass is a pair of immense quarter-columns whose stop-fluting ends in a bold curve in the manner of furniture from nearby Winchester, Virginia. At the top of each column is a large flat frieze adorned with a carved swag. The unusually large case is supported on foreshortened cabriole legs with ball and claw feet that originally were secured with massive, L-shaped, wrought-iron brackets nailed into mortises on the backs of the legs and the bottom board. Almost identical feet that retain their original iron brackets survive on an equally remarkable desk and bookcase Shearer made for a Winchester client (MESDA acc. 2979). The fall boards of both desks are ornamented with inlaid, interlaced vines and bellflowers. Many of these inlays were made of end grain wood, perhaps in an effort to attain greater contrast with the surrounding areas. The reverse serpentine case facade on both desks, one of Shearer's favorite designs, may have been taken from the 1793 edition of the Cabinet-Maker's London Book of Prices.

The bail and rosette handles on the CWF desk were conventionally set, but the pulls on many of Shearer's case pieces were arranged vertically. Often thought to be another indication of the craftsman's eccentricity, the technique may instead reflect Shearer's attempt to align the pulls with the flat end spaces on the reverse serpentine drawers, thus highlighting the overall verticality of the forms. The vertical placement of the pulls also makes them easier to grasp. Most of Shearer's other construction techniques mirror standard conventions. Large case drawers and interior desk drawers are dovetailed and bottomed in the traditional manner; the stock sizes for side and bottom panels are typical as well. Following backcountry custom, each case drawer is supported on an interior frame that consists of two side runners tenoned into the back of the drawer blade and into a rear rail secured with nails driven through the backboards. In many respects, the sturdy construction of Shearer's wares brings to mind furniture made by German artisans in the northern part of the Valley.

Some unusual aspects of Shearer's designs may have symbolic meanings that are not apparent at first. For instance, his highly developed and architectonically inspired writing interiors can be interpreted as more than just work places where letters were written. They also serve as personal theaters where users played out the dramatic affairs of business and everyday life. This theater parallel, also clearly seen in the Luckett desk, reflects an Anglo-American tradition evidenced in early design books. The central prospect on the CWF desk features a large vaulted doorway that functions as a proscenium arch. The vaulted pigeonhole recesses work in a similar way. Projecting into the foreground and serving as the main point of interaction, the leather-covered writing surface is a stage that is defined on its outer perimeter by a wooden frame.

In sum, Shearer's furniture-making legacy is significant. As much as any American cabinetmaker, he merged popular urban styles with his own inspired artistic vision. More than mere copies or interpretations of conventional designs, the goods Shearer made considerably expanded the existing regional craft repertoire. His imaginative creations prove that modern analyses of American furniture making must give fair scrutiny to the influence of cultural settings, for few things are as constant as the power of time and place in affecting the shape of material goods. Early America was a remarkably diverse nation and there necessarily existed multiple standards of craft excellence that defined the products of different places. These standards did not always conform to the norms of the coastal urban centers. Shearer's sense of design and construction certainly reveal personal idiosyncrasies, but at the same time his work parallels local standards and traditions. Moreover, the strong political sentiments that are revealed in his productions reflect notions that were shared by many European immigrants in the Valley. Ultimately, Shearer was a southern artisan whose work reveals much about himself, his heritage, and the cultural traditions of the setting in which he worked.

InscribedA column of figures written in ink remains on a side panel of the farthest right document drawer. Given the large number of marks on other Shearer objects, it is possible that additional marks and perhaps signatures are under the black varnish on the backboards and large drawer interiors.

MarkingsNone

ProvenanceThe desk was acquired from Priddy & Beckerdite of Richmond, Va., in 1990. The firm bought the piece from Robert M. Hicklin, Jr., Inc., of Spartanburg, S. C. Hicklin obtained it from a West Virginia antiques dealer who found it in California during the 1970s.

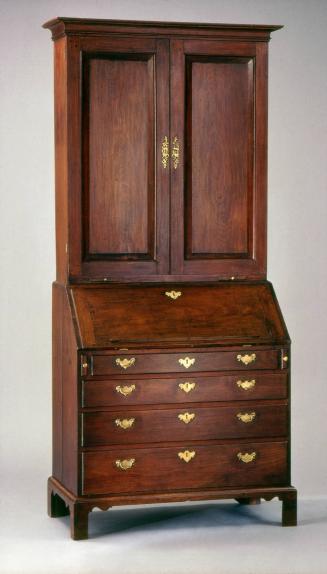

1770-1780

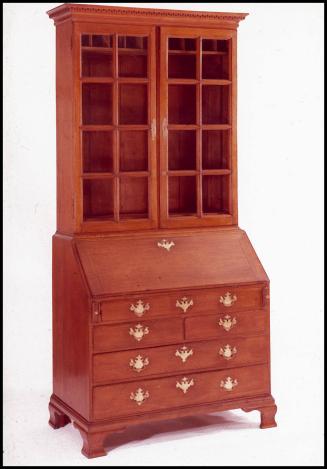

ca. 1795

1760-1790

1750-1760

1760-1780

1700-1720

1765-1800

1789

1790-1815

1750-1775

1800-1815

1760-1790