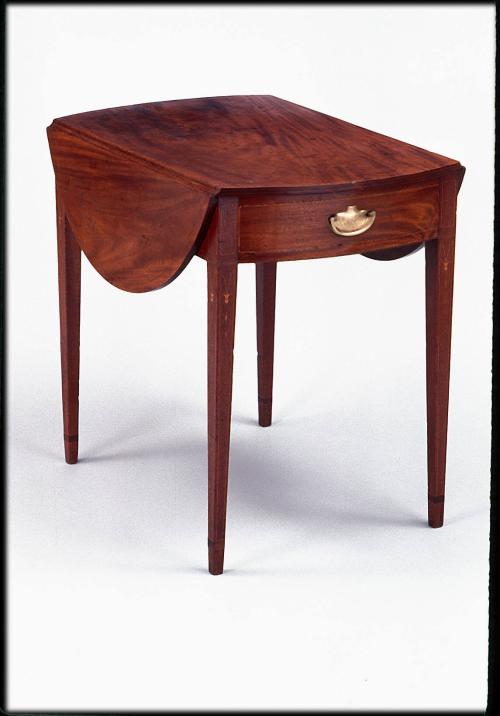

Pembroke Table

Dateca. 1800

MediumMahogany; black walnut; tulip poplar; yellow pine; white pine; lightwood, ebonized lightwood, and resinous inlays.

DimensionsOH. 27 7/8; OW. (closed) 20 3/4; OW. (open) 38 7/8; OD. 30.

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1930-119

DescriptionAppearance: breakfast table with single drawer and two drop leaves; oval top with triple string inlay; bowed end rails with string inlay; original urn-shaped drawer pull; four tapered legs with cow/goat skull, drop, cuff, and string inlays.Construction: Screws set in wells secure the mortised-and-tenoned frame to the top. Screws set in wells on the end rails attach the frame to the top. The hinge rails pivot on finger joints that protrude through the inner guide rails. The drawer is supported by nailed-on runners, and the drawer stops are nailed to the inner rails. The bottom of the dovetailed drawer, beveled along the sides and front, fits into grooves. It is flush-nailed at the rear.

Materials: Mahogany top, leaves, legs, drawer front veneer, drawer blade veneer, and end rail veneer; black walnut hinge rails; tulip poplar drawer front and end rail laminates; yellow pine inner rails, drawer blade core, drawer bottom, drawer runners, and drawer stops; white pine drawer sides and drawer back; lightwood, ebonized lightwood, and resinous inlays.

Label TextThe oval top, tapered legs, and alternating light and dark stringing of this Virginia-made breakfast table are similar to many British and American examples of the same period, but the animalistic inlays near the top of each leg represent an unusual departure from the norm. These elements are rooted in antiquity and represent the borrowing of a classical architectural tradition by a furniture maker. Each inlay depicts the skull of a horned animal. Collectively known as bucrania, sculpted models of cow, ram, ox, and goat skulls first adorned classical Roman altars as fertility symbols and allegorical references to animal sacrifice. The ancients also used bucrania on sarcophagi and other funerary forms and applied them to architectural friezes. These decorations remained in limited use for several centuries afterward and were revived during the Renaissance as exterior architectural motives and interior ornaments for mantelpieces and the like.

In the late eighteenth century, bucrania began to appear on American buildings, another indication of the renewed interest in the classical world. Thomas Jefferson placed them in the friezes on several of his structures, including Monticello. In 1822, he commissioned William John Coffee, a British painter and sculptor working in New York, to provide cast lead bucrania for the entablatures of two rooms at Poplar Forest, Jefferson's retreat in Bedford County, Virginia. Jefferson noted that "in my middle room at Poplar Forest, I mean to mix the [human] faces and ox-sculls[,] a fancy which I can indulge in my own use, altho in a public work I feel bound to follow authority [design books] strictly." When Coffee shipped the Poplar Forest ornaments, he also enclosed "Enrichments for the University," probably a reference to the bucrania Jefferson installed on Pavilion 2 at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

While the architectural use of bucrania is well documented, their appearance on early American furniture is rare. Few other southern examples are known, except for those on a neoclassical card table included in the 1952 exhibition of southern furniture at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The inlay on that table is far more stylized and, together with the object's different structural and stylistic vocabularies, clearly suggests the hand of an artisan unrelated to the CWF table.

Several features on the CWF table point toward production in or near Norfolk. The delicately wrought inlay work and the thin mahogany veneers represent approaches that in the upper South most often are associated with Norfolk cabinetmakers. Further supporting that attribution are the boxwood stringing and white pine drawer sides and back, woods not commonly found on Piedmont and backcountry furniture. Finally, the bucrania are highlighted with mastic or pitch fills, tar like substances generally used by furniture makers in early national Norfolk.

Despite its coastal attribution, the table may have been owned inland, as were many other pieces of eastern Virginia furniture shipped upriver from port cities to rural districts. The underside of the table is signed "S. Ragsdale," an early inscription that may refer to Samuel Ragsdale, a resident of Lunenburg County in south central Virginia. The same hand also drew several faces that almost look like caricatures of the bucrania on the legs. Whether the Ragsdale signature represents a maker or an early owner is impossible to know at present, but no cabinetmakers of that name have been identified.

InscribedThe table is signed "Ragsdale" and "S. Ragsdale" in several places on the underside of the top. Accompanying these ink inscriptions are renderings of flowers and faces. The bottom of the drawer is marked "9609-43" in chalk, probably a modern dealer's inventory number.

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceThe table was purchased by CWF in 1930 from Mrs. Archibald Robertson, a Petersburg, Va., antiques dealer who specialized in southern decorative arts.

1790-1800

1800-1815

c. 1790

ca. 1790

1790-1810

ca. 1800

ca. 1810

1790-1810

1805-1815

1790-1815

1790-1810