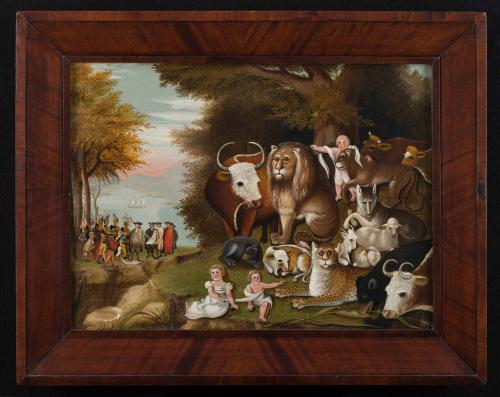

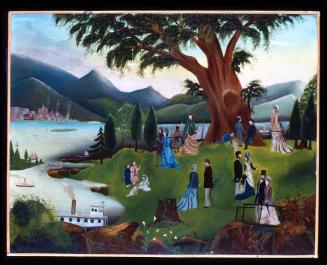

The Peaceable Kingdom

Date1832-1834

Attributed to

Edward Hicks (1780-1849)

MediumOil on canvas

DimensionsOther (Unframed): 17 1/4 x 23 1/4in. (43.8 x 59.1cm)

Framed: 24 x 30 1/4 x 2 1/8in. (61 x 76.8 x 5.4cm)

Credit LineFrom the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Collection; Gift of David Rockefeller

Object number1932.101.1,A

DescriptionA grouping of three children and various wild and domesticated animals fills slightly more than the right half of the composition. At left, a group of colonists and Indians stand in the distance on a riverbank with, beyond them, a sailing vessel visible in the rays of a setting sun. The 3 1/2-inch mahogany-veneered flat frame is a period replacement.

Label TextEdward Hicks painted more than sixty versions of The Peaceable Kingdom, varying his pictorial interpretations of Isaiah 11:6-9 to reflect his personal struggles with Quaker theology and, particularly, his anguish over the sect's split into Hicksite and Orthodox believers.

During the early 1830s, Hicks evolved a kingdom format featuring a seated lion. His earlier use of motifs borrowed from print sources was gradually and systematically replaced by the general composition and arrangement illustrated here, and it was thoroughly Hicks's in concept and design.

Hicks's pictures of the 1830s reject the grapevine as a symbolic proclamation of salvation achieved through outward sacraments. Instead, his compositions emphasize salvation attained by the "light within." Note the ears of grain in the lion's mouth. By disobeying nature's law and choosing vegetation over meat, the beast has yielded his self-will to the divine will of God, thereby illustrating the heart of Quaker theological teaching.

As controversy between the two Quaker factions continued, the expression "inner light" became associated with the Hicksites, while "blood of Christ" came to represent orthodoxy. As a supporter of the Hicksite movement, the artist must have felt compelled to incorporate symbolism that reflected his partisan views.

Other changes evident in Hicks's middle period kingdoms, including this one, include the smaller size and less prominent placement of the child who leads the animals. It is the animals that occupy most of the space, and it is their beautifully detailed fur and intense gazes, particularly those of the lion and leopard, the fiercest creatures, that capture the viewer's attention. These changes are also closely tied to Hicks's growing need to express verbally in his ministry and visually in paint his anxiety surrounding the Quaker controversy.

It is difficult to view these creatures without sensing a kinship with them and something in the nature of an unspoken dialogue. For Hicks these were the souls of mankind in symbolic form; perhaps we also respond to these meanings, although we remain forever removed from the fears and struggles so carefully intermingled among the colors and wonderful textures captured in Hicks's painting.

ProvenancePurchased from Edith Gregor Halpert, Downtown Gallery, New York, NY, by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller in 1932; given to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, by Rockefeller in 1939; transferred from the MoMA to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, in 1949; purchased from the Metropolitan Museum of Art by David Rockefeller and given by him to CWF in 1955.

1826-1828

1822-1825

Probably y1860-1872

ca. 1845

1830-1835

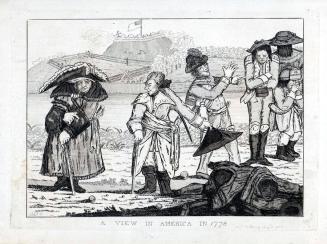

August 1, 1778

ca. 1875

1775