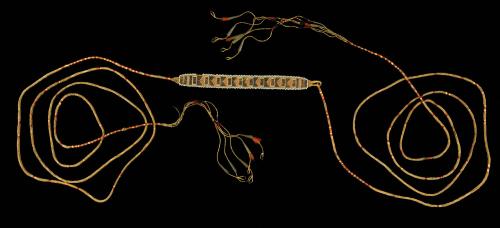

Native American prisoner halter

Date1775-1800

MediumApocynum fiber (native hemp or dogbane), porcupine quills, sinew, deer or moose hair, tin, glass beads, copper alloy, deerskin

DimensionsOL: approximately 22 feet.

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1996-816

DescriptionAmerican Indian prisoner halter consists of a twined woven halter strap, measuring 12 1/2 by 1 1/4 inches, furnished with a loop at one extremity and tapering into a long braided cord at the other end. A similar cord is attached to the loop, both cords measuring 10 1/2 feet long, inclusive the multiple strings terminating at their ends into metal cones. The strap is made of carefully prepared string and thread of vegetable fiber; the warp made of inner-bark fibers of elm or basswood; the weft of Indian hemp, most probably Apocynum Cannabinum. The latter is sometimes referred to as milkweed, though it is actually a dogbane. The fine weft twined over the coarser warp strands created the surface of thirteen parellel ridges. The weaving was most probably started in the middle of the strap, its width at both ends reduced by means of bringing the warp strands together in the twining process. Continuation of the warp strands at one extremity created the braided cord. Also the separately attached cord is braided of the same material. Except for the outer ridges the surface of the strap is decorated with dyed and non-dyed moosehair in a brocading technique called "false embroidery", in which the colored hair is wrapped around the weft element during the process of weaving. In addition to (now faded) red and black dyed hair also the natural off-white winter hair is utilized to create a repeating pattern of rectangular and triangular designs. The strap is edged with white trade beads in a technique called "two-bead edging", whereby the beads are placed in alternating positions, vertical and horizontal. The two cords are braided to form a square section, at intervals wrapped with red and yellow porcupine quills. They terminate into five looped strings with red-dyed hair tassels in tin cones at the ends. Most of the hair tassels have been lost, which is common for artifacts of this type and age. (Description by Dr. Ted. J. Brasser, Peterborough, Ontario).Label TextThe colonizing of North America during the seventeenth century and the exponential growth during the eighteenth-century created nearly constant tension and conflict between Europeans and Native Americans. The violence led to an increased practice of “mourning war,” or a method in which Native American communities grieved by the adoption and assimilation of captives. One French colonial officer remarked on the Iroquois, “They rarely kill those who can be taken prisoner, because the honor and advantage of victory lie in bringing prisoners back to the village.”

From 1741 to 1742, a Frenchmen named Antoine Bonnefoy left a journal that detailed his capture and later escape from the Cherokees. Captured with five others along the Ohio River, Bonnefoy wrote “we were tied separately, each with a slave’s collar around the neck and the arms” and his captor reassured him through signs that “no harm should come” to him. In February 1742, he recounted his adoption into Cherokees and the ceremonial role of his collar becomes quite clear when it was removed by his adopters from around his neck. These collars functioned as both a practical restraint and a symbolic icon.

In 1830, Kentuckian John Tanner (c. 1780 – c. 1846) published a book about his captivity and later adoption into the Anishinabe (Ojibwe) people. He remarked on the practice and making of prisoner strings, similar to the halter on view. Tanner wrote:

Tah-ko-bitche-gun (Prisoner String)…These cords are made of the bark of the elm tree by boiling, and then immersing it in cold water; they are from twenty-five to fifty feet in length, and though less than half an inch in diameter, strong enough to hold the stoutest man. They are commonly ornamented with porcupine quills, and se-bas-kwi-a-gun-un, or rattles are attached at each end, not only for ornament, but to give notice of any attempt the prisoner may make to escape. The leader of a war party commonly carries several fastened about his waist, and, if in the course of the fight any one of his young men takes a prisoner, it is his duty to bring him immediately to the chief, to be tied, and the latter is responsible for his safe keeping.

The prisoner halter on view came into the Colonial Williamsburg collection with no history, probably collected by an English traveler during the late eighteenth century. The woven symbols on the collar, when read vertically may relate to Mohawk iconography. A pattern of dyed black and red deer and moose hair creates nine complete houses along the collar, possibly representing the nine chiefs of the three Mohawk clans. The tenth house on the collar remains incomplete and not formed, a symbol related to the process of captive taking, adoption, and the making of new relatives.

1759 (dated)

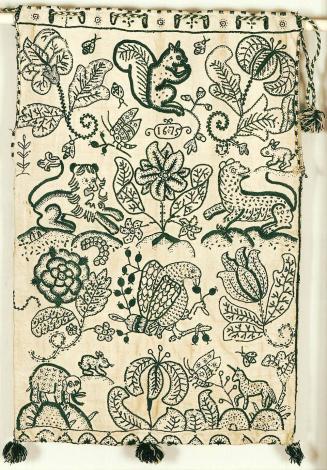

1675 (dated)

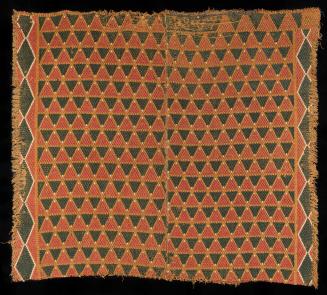

ca. 1810

ca. 1845

1793

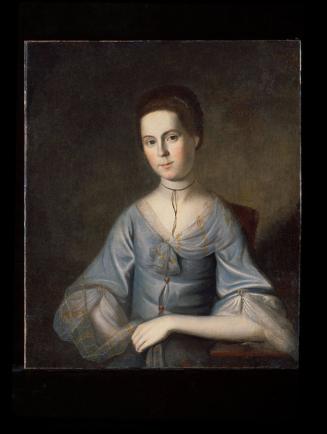

1776 (dated)