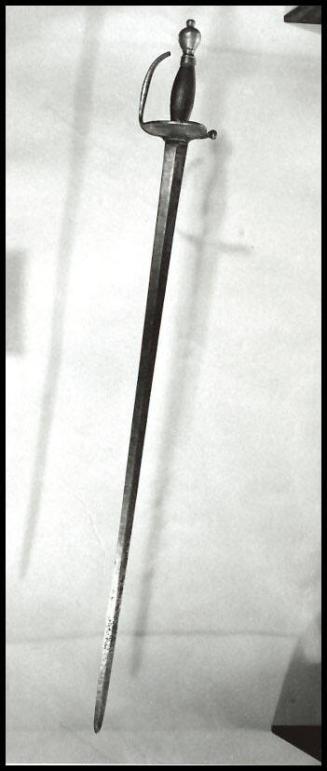

"Potter" Light Dragoon Saber

Date1778-1781

Maker

James Potter

MediumSteel, iron and walnut

DimensionsOL: 42 3/4"; Hilt: 7 1/4"; Blade: 35 1/2"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number2004-15

DescriptionLarge size light dragoon saber with a 4-slot iron stirrup hilt and a broad, tapering knucklebow terminating in a ring which seats below its tall, ovoid pommel. The spiraling walnut grip was originally covered with leather and bound with twisted wire, both of which are now missing. An iron ferrule remains in place at the bottom of the wooden grip. Its long curved blade is single edged, and while it is unfullered, it has a prominent ricasso and a false edge running back from the tip...Label TextWorking on Maiden Lane in lower Manhattan, sword cutler James Potter produced almost 1,600 of these signed scimitar-bladed sabers for the office of the Inspector General of Provincial Forces. Documentary sources show that Potter's sabers were issued in large numbers to men serving under Tarleton and were heavily used in both the mid-Atlantic and Southern theatres of war. Potter's swords were so desirable that the Continental Army captured them for their own use whenever possible, and even made imitations of them.

************************

Complacency with long held and extensively published notions has all too often stood in the way of the true understanding of a particular weapon and it's importance to history. While the arms student has been aware of the swords created in the New York City shop of James Potter at least since Peterson's Arms & Armor in Colonial America appeared in 1956, few have recognized the tremendously significant context surrounding the production of these weapons.

Instead, the Potter sword, in achieving legendary status, has simply become universally accepted as an unquestionable example of an American-produced Revolutionary War weapon. And with not much else to go on, the commonly accepted impression is that since the sword was American-made, then of course it must have been produced for the benefit of the patriot cause. Let's start fresh, by stripping away the assumption and lore and looking at the cold hard facts.

Given: one James Potter, a sword cutler working on Maiden Lane in lower Manhattan, produced a large number of virtually identical horseman's swords during the Revolutionary War period. And he had the audacity to boldly strike, or have his name struck, into just about every blade. Each printed mention of one of these swords agrees, and the primary source documents fully support and bear this out. But that is where the harmony ends.

Immediately after the Declaration of Independence was publicly read in New York City on 9 July 1776, an angry mob demolished the gilt-lead statue of George III recently installed in Bowling Green, at the foot of Broadway. The broken chunks of the king were carted off and cast into tens of thousands of musket balls, vital munitions to the escalating patriot war effort. Shortly thereafter, the war indeed came to the city, first manifesting itself as a floating forest of masts spotted off of Long and Staten Islands.

In short order, the British Army and Navy clobbered George Washington and his fledgling Patriot forces, and beat them back all the way up and across the Hudson River to New Jersey by the fall of 1776. Despite a valiant defense, the city fell relatively easily and remained in the hands of the British until they decided to leave late in November of 1783.

With New York City firmly in British hands for the lion's share of the war, it is obvious that Potter wasn't making his swords for the Patriot cause. While one could make the argument that Potter did so before the British occupation, there is no evidence to support the idea. Besides, the Continental Army didn't yet know they would have a huge need for dragoons, let alone dragoon sabers, that early in the war. Since the documents don't support Potter as a patriot sword maker, what do they tell us?

The earliest documentary appearance of James Potter is in the fall of 1776, when his name appeared on a long list of "inhabitants of the city and county of New York" who endorsed a loyalty oath on 16 October 1776 (which was printed in the 4 November 1776 New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury). While no mention of his profession is made, it tells us that he was 1) a New Yorker and 2) fiercely loyal to the Royal Government. Had Potter been in business as a sword cutler in New York City before the fall of 1776, surely he would have run advertisements alongside those placed by other local cutlers like John Bailey, James Youle, Charles Oliver Bruff and Richard Sause. As he was probably not a newcomer to the trade, it seems likely Potter was working as a journeyman sword cutler, perhaps for one of the abovementioned masters, before the British took the city.

It is almost two years before our Mr. Potter appears in the records again, but this time things are different, as he is out on his own and actively looking for help. Obviously meeting with quick success, he only had to run this ad in the Royal Gazette twice, on 13 and 17 June 1778;

Wanted

A F O R G E R

That perfectly understands his Business,

to whomgood Wages will be given,

also two or three F I L E R S,

Who are well skilled in that Branch,

they will meet with very generous encouragement,

by applying to

JAMES POTTER;

Sword Cutler in Maiden-Lane.

While one might wonder why Potter waited so long under the protective wing of the British military machine to begin producing his swords, the answer is simple. Much like the rebel forces, there was little need for horsemen's swords by the Crown forces during the first few years of the Revolution. All of this changed in 1778 and 1779, as the war moved South, and the numbers of Loyalist units, of all sorts, exploded. In 1776, there were less than a dozen and a half Provincial regiments (exclusive of militia) and almost 80, from Florida to Nova Scotia, by 1781. Most prominent amongst these units were the 5 regiments officially put on the newly-created American Establishment;

- Queen's American Rangers (Simcoe's), or 1st American Regiment (1779)

- Volunteers of Ireland, or 2nd American Regiment (1779)

- New York Volunteers, or 3rd American Regiment (1779)

- King's American Regiment, or 4th American Regiment ( 1781)

- British Legion (Tarleton's), or 5th American Regiment (1781)

Others bore intrepid names like the King's American Dragoons or the American Legion, commanded by the much-hated Benedict Arnold. With the dramatic expansion of the American forces fighting alongside the British, many of these units began to add mounted companies or converted to entirely mounted units to meet the need for such highly mobile, fast and effective troops. While firearms, such as pistols and carbines, were certainly useful to the 18th century American dragoon, those serving both sides in the late 1770s and early 1780s preferred to use swords as their primary arm.

Firearms for these Provincial dragoons, or "hussars" as they often called themselves, were supplied by the Board of Ordnance headquartered at the Tower of London. Much like the regular units of the British army, responsibility for the provision of swords fell to the units themselves and were not issued from government stores back in London.

Instead, responsibility fell on Col. Alexander Innes, appointed to the post of Inspector General of Provincial Forces in early 1777. Rather than contract for the supply of swords through an agent 3,000 miles away, Innes' office sought to procure the needed weapons locally, and found their man in James Potter. It is the lucrative contract with Innes that spawned Potter's need for workmen in mid 1778 - and today's famous cavalry saber.

All of the expenditures Innes' office incurred on behalf of the Provincial forces are documented in his official 16 February 1785 summarized account to the government, covering the entire period he held the post, 29 January 1777 to 30 September 1782, now preserved in the Public Record Office, Kew, England (AO 3/118).

The "Rosetta Stone" of the Potter sabers is now illuminated! Not only does this account book prove just what side of the Revolution these weapons were made for, but it also tells us that in the short span of late 1778 though the end of 1781, some 1,580 were produced, and they cost £2.6.8 per sword!

Adding this knowledge to the pile of facts already on hand, an interesting question now arises. Other than Potter himself, his shop on Maiden Lane apparently employed a tiny labor force of only one forger and two or three filers, as per his 1778 help-wanted ad. So one is forced to ask, did Potter's shop make his swords and their scabbards from tip to pommel, or were certain components made elsewhere?

In the absence of any further documentation or proof, there is the possibility that Potter's blades were made for him in England. With New York in British hands, the importation of such blades would have been no problem. Further intimating this is the fact that Potter's blade are far and above the quality of anything known to have consistently been produced in large numbers in America, either before or after the Revolution. One just can't say for sure. Regardless, he deserves a spot in the pantheon of early American industrial giants.

During the period in question, Potter's neighborhood was one of small, mostly wooden buildings that were occupied as either businesses or residences, with a few small manufactories here and there. Since the property records of occupied New York City are scarce, it has not been possible to locate Potter's property on Maiden Lane, which ran from Broadway to the Fly Market at the East River. Today it follows the same course, but runs another few blocks east due to subsequent landfill.

A check of the Manhattan land records, now kept at the Register's Office of New York County, turned up no real estate transactions involving James Potter as either the seller (grantor) or the buyer (grantee) during the last half of the 18th century. Therefore, we can conclude that Potter was either renting his premises or he only owned them for the duration of the British occupation. Perhaps he was granted confiscated Rebel property on Maiden Lane?

Since there was no running water on Maiden Lane, Potter's sword factory couldn't have had a water-wheel powered trip hammer needed for large scale iron and steel production, although he could have used horses for some of the heavy labor, via a horse gin. However he did it, at the least Potter's small shop produced almost 1,600 swords, and with most mounted contingents of Provincial regiments numbering less than a hundred, it would seem that there were enough to go around.

One letter, written to Gen. Cornwallis as Commander in Chief of the British land forces in the South (PRO 30/11/6, folios 162-3), by Col. Innes on 31 May 1781, gives the rate at which Potter could normally produce swords (not his maximum capacity, however). Amongst other equestrian supplies desperately needed to equip 300 horsemen serving with Tarleton's Legion, then campaigning in Virginia (under Cornwallis), Innes advises that;

"67 Swords are now in Store. 50 more are at the Cutlers, he can finish 25 P(er) week and shall go on Compleating Swords."

Certainly Innes and Potter were scrambling to get swords ready to be shipped south to replace those lost in action and to equip British Legion troopers, be they new recruits or the ad-hoc mounted infantry (men from the 23rd, 63rd, 76th and 82nd Regiments, along with the North Carolina Volunteers) created to swell the contingent. Since the production period of the swords coincides with the drastic expansion of mounted Provincial forces (those American regiments loyal to Britain), it can be stated that they were also issued to other units like the Queens Rangers, Benedict Arnold's (American) Legion and the King's American Dragoons, amongst others higher-up in the food chain of Provincial forces.

Another unit is almost certain to have been issued with Potter's swords. Raised in East Florida in 1778 from disaffected South Carolinian loyalists persecuted by their rebellious neighbors, the South Carolina Royalists had two troops of rifle dragoons and became an all-mounted regiment in the spring of 1781. Since their Commanding Officer was the same Col. Innes who contracted for the swords as Inspector General of Provincial Forces, can you guess what he issued to his own troops?

Sometimes when you do your job well, or make an especially effective "thingy," there are unintended consequences, some of which are pleasant. Others are shocking, and such was the case with Mr. Potter's sabers. In war, one of the many goals attempted by combatants is the capture of necessaries, be it food, clothing, ammunition or arms. By doing this, you not only deprive your enemy of his vital supplies, but you improve the situation of your own troops.

With effective cavalry sabers a scarcity in the Continental Army, and with the increasing need for mounted troops by Washington's forces, the Potter saber became a sough-after prize, in a fashion similar to the German Luger of WWI and WWII fame, but with one difference. A Potter sword wasn't just a nifty souvenir; it became the primary arm and a potential lifesaver in the hands of the American dragoon!

In a sea of swords purporting to be "Revolutionary War," those made by Potter were celebrated by the soldiers who actually used them in combat, not just by modern arms collectors. Furthermore, they are unique in that they were actually mentioned by name, in crystal-clear unmistakable language, in a number of early accounts.

Before Robert E. Lee was a glimmer in his father's eye, "Light-Horse Harry" Lee's Legion was thundering through the south, clashing with British and Provincial troops from Georgia to Virginia. Lee was known as a top-notch cavalry commander, who went to great pains to see to every need of his corps, and insured that his men were equipped as well as possible. In memorializing Light-Horse Harry in his 1822 Anecdotes of the Revolutionary War in America…, one of Lee's subalterns, Lt. Alexander Garden, wrote;

"every individual of the corps, was armed with a Potter's sword, the weapon most highly estimated for the service, taken in personal conflict from the enemy."

Often fighting alongside Lee's Legion were the mounted men serving under Brigadier General Francis Marion, the "Swamp Fox." In Weems' fictionalized biography of Marion published in 1809, a trooper named Macdonald, in being regaled as a superhuman Patriot, was said to have had such strength that:

"with one of Potter's blades he would make no more to drive through cap and skull of a British dragoon, than a boy would, with a case-knife, to chip off the head of a carrot."

Regardless of how handy Macdonald really was with a saber, a Potter sword (with an altered grip & pommel) now in the Charleston Museum, was purportedly carried by Serjeant Ezekiel Crawford of Marion's Brigade, adding credence to Weems' statement.

Banastre Tarleton himself tells us about the largest cache of Potter swords that fell into American hands at one time. In his 1787 A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America, Tarleton transcribes Henry Knox's return of military stores surrendered at Yorktown (on pp.451-4), which included 273 "horseman's swords" amongst other sorts. With the only cavalry at the siege being Tarleton's Legion, the Queen's Rangers, some North Carolina Volunteers (often serving with the Tarleton's mounted contingent) and a few 17th Light Dragoons, it can be stated that a lion's share of those 273 must have been Potter swords.

If the use of captured Potter sabers wasn't enough, the Patriots took it one step further by attempting to copy them. James Hunter's iron works on the Rappahannock River in Virginia was producing armaments in large quantities for the Continental Army, when Maj. Richard Call of the 3rd Regiment of Light Dragoons wrote the following to Virginia's Gov. Thomas Jefferson on 29 March 1781:

"I have received Express from Lieut. Colo. Washington one Horseman's sword taken in the late action at Guilford Court House, which he directs me to send Mr. Hunter as a pattern and have swords made for the men."

Further along in the letter, Call states;

"the sword is the most destructive and almost only necessary weapon a Dragoon carries. (Calendar of State Papers [Jefferson], Vol. I, p. 606)."

Since the only Loyalist (or British, for that matter) cavalry at the battle of Guilford Courthouse was the mounted contingent of Tarleton's Legion, who had Potter sabers, the example sent to Hunter for replication was certainly a Potter, having been lost by said unit. However, it wasn't until after combat had effectively ceased (late November of 1781) that Hunter's swords, numbering 1000, were ready for delivery.

While Col. Innes was well aware of those swords lost in combat to the enemy (since he had to replace them), he may never have known how well they served his intended victims. Potter probably didn't know either, but heck, the loss of his products in combat was good for business.

As the last entry for swords coming into the inventory of the Provincial forces takes place between the first of October of 1781 and the last day of that year, it can be assumed no more Potter sabers were need. Also occurring during that span of three months was the disastrous surrender of Cornwallis' forces at Yorktown, more or less bringing the war to a halt - and obviously the need for more horsemen's swords. Potter continued repairing swords, and no doubt producing a few for private customers after his gig with the Provincial forces ended.

The handwriting was then on the wall for the Loyalists citizens of New York City. The war was lost, and recognized peace was just on the other side of some diplomatic wrangling and parchment scribing. With the formal ratification of a peace treaty, these New Yorkers knew their protectors - the British Army - would be leaving, and they would have to make a choice. Should they stay, and endure the wrath of the victorious and vindictive Americans, or should they get out of town?

By the spring of 1782, either business took a turn for the worse (no surprise), or Potter became restless in his home town. In an attempt to sell what may have been the family homestead (and workshop), he ran an ad in the 27 April 1782 Royal Gazette reading;

TO BE SOLD

A HOUSE near Maiden-Lane,

in good repair, and very convenient for a small Family.

The Price is One Hundred Guineas.

Apply to James Potter, Sword Cutler, Maiden-Lane.

The fact that Potter is indeed selling property (for gold coin, nonetheless) shows he wasn't just a renter. However he came to own it, the lack of officially filed deeds almost certainly has to do with the low priority such civil matters held in a city run by a military government. Furthermore, Potter must have been aware that his claim to the property would not have been honored by the Americans once the British left New York. A clue to the location of Potter's property may also be gleaned from this ad. Since the house was "near" Maiden Lane, it is likely that it stood in the central part of the block, perhaps adjoining his workshop on the street front proper (ie; 'in Maiden Lane').

Six months later came further proof of Potter's decision to remain under the protective wing of King George III, when he was preparing to shut down his business. Appearing in the 2 October 1782 issue of the Royal Gazette, Potter ran the following plea:

The Subscriber intending for England very soon,

Desires those to whom he is indebted to call and

Receive payment; and requests those indebted to him to

Discharge the same without further notice. - Those

Gentlemen who have left Articles in his hands to repair,

Are desired to take them away, otherwise he will be

Under the necessity of disposing of them to pay the expences of repairing.

J A M E S P O T T E R,

Sword Cutler, Maiden-Lane.

New-York, 1st October 1782.

One must wonder what sort of business Potter was conducting during the first nine months of 1782. While it is certain he was repairing edged weapons, he was likely repairing other articles as well. But was he peddling breast milk too? Apparently so! Our final evidence of James Potter in New York City appears with his ad of 16 November 1782, placed in his favorite paper, the Royal Gazette;

A W O M A N with a good breast

of Milk would be glad to take a

Child to nurse ; she can have an

unquestionable character by ap-

plying at Mr. Potter's, Sword-

Cutler, Maiden Lane ; any person

wanting her will be waited on by

enquiring at the above place.

James Potter never left for England as he advertised in October 1782, but shortly after the wet-nurse ad ran, he and his family left for good. Some time the next year, he reappears in the burgeoning Loyalist settlement of Shelburne, Nova Scotia, where his family, numbering eight persons, has settled. In recognition of his service to the Crown, Potter is generously rewarded with land. He is granted one farm, one lot in town, and one lot on the waterfront. While we lose him in post-war Nova Scotia, one thing is for sure - he didn't stay in New York to carry on his trade. Considering the notoriety of his swords and the horrible deeds committed with them, he could have paid for his skill and loyalty to the king with his life, had he remained in his hometown.

As such, the notion that Potter worked in New York City after the British evacuation in late November 1783 is simply ludicrous. This commonly accepted misconception is probably linked to the following classified ad that ran numerous times in the New-York Daily Gazette between 13 March and 25 April 1789:

Light-Horse Swords,

Of Potter's make, to be sold Cheap by the

Quantity, by W. Fosbrook, Surgeon's

Instrument Maker, No. 58, Queen-Street near Peck's-Slip.

N.B. Country Produce will be taken in Payment.

This ad has apparently been misinterpreted for years, due to the lack of other available facts concerning Potter. It is clear from Innes' records that Potter was paid for the sabers supplied to the Provincial forces. When the need for arms evaporated with the cessation of most hostilities after the capitulation of Yorktown in late 1781, there would have been no reason for Potter to produce these extremely plain but serviceable weapons for private Loyalist customers in the New York City area.

Clearly, what Fosbrook was peddling was the inventory of unissued sabers left behind by Innes' office when the city was evacuated. Once the victors reclaimed the city, Loyalist and British Governmental property was confiscated and sold at auction, which is probably how Fosbrook (who wasn't a sword cutler, by the way) came into a supply of Potter swords, and was willing to flog them off for vegetables, meat or perhaps some dairy goods. The true value of this ad is in its terminology, proving that "Potter's" swords were widely recognized as of superior quality and desirability in the 1780s.

In conclusion, we now know that the Potter sword, produced in New York City for the Provincial forces, became an exceedingly prized weapon by both sides and was contemporarily renowned. Unlike others produced in America during the war, like the fine silver hilts of Bailey and Brasher, Potter swords were real combat weapons that saw very heavy service. Therefore, the Potter sword truly is the ultimate sword of the American Revolution!

Markings"POTTER" struck into the inboard ricasso of the blade.

ProvenanceFormerly in the collections of Andrew Mowbray and Thomas Wnuck (1943-2002).

Exhibition(s)

ca.1778-1783

ca.1690-1710

ca.1740-1750

ca.1740-1760

ca. 1760-1785

ca.1770-1780

ca.1775-1790

1770-1790

ca. 1690

ca. 1745-1765