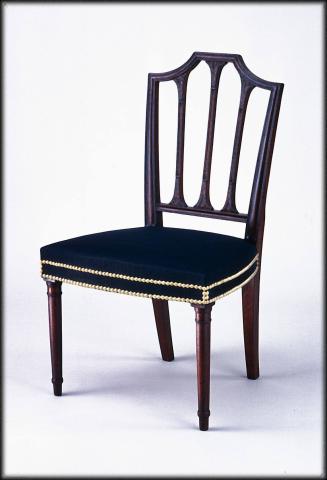

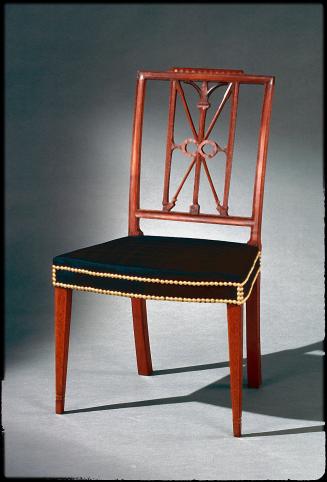

Armchair, converted from side chair

Date1790-1810; altered ca. 1825.

MediumMahogany, oak (by microanalysis), and tulip poplar (by microanalysis).

DimensionsOH: 37 1/2" OH seat rail: 17" OW seat: 18 5/8 " OD seat: 16 1/4"

Credit LineAcquisition was made possible in part through the generosity of Kelly C. Schrimsher.

Object number1991-637

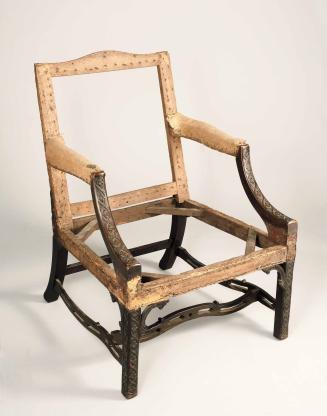

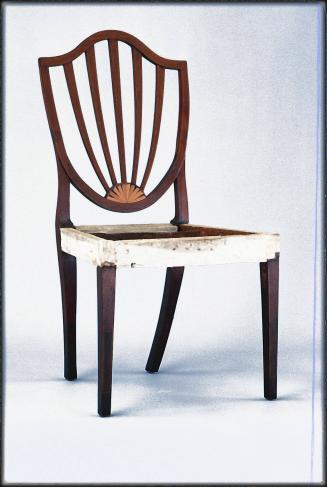

DescriptionAppearance: Shield-back armchair with three-ribbed, foliate-carved splat; over-rail upholstery; tapered legs.Construction: The base of the splat is set into an open mortise on the splat rail, and the joint is concealed with an applied carved panel. The upholstery covers the front and side seat rails but terminates in a rabbet on the upper edge the mahogany rear rail. A double row of brass nails finished the original upholstery. The serpentine front and bowed side seat rails are shaped on both their inner and outer surfaces. Open diagonal braces are let into each of the four corners of the seat frame, and the medial stretcher is tenoned into the side stretchers. The front legs extend above the seat rails and are tenoned into the arm supports, which are in turn tenoned into the arms. Each arm is secured to its stile with a single screw driven diagonally from the back.

Materials: Mahogany crest rail, splat, splat rail, rear seat rail, stiles, arms, front legs, and stretchers; oak side and front seat rails (by microanalysis); tulip poplar diagonal corner braces (by microanalysis).

Label TextIn 1800, the nine-year-old District of Columbia was anything but a major urban center. At the core of its one hundred square miles was Washington, an embryonic town of fewer than three thousand people. Just up the Potomac River lay the older city of Georgetown, recently annexed into the District from the state of Maryland and home to perhaps thirty-five hundred souls, while a few miles downstream was Alexandria, acquired from Virginia together with its population of some four thousand. Despite its status as the nation's capital, in reality the District was a loosely associated group of three moderately sized towns widely separated by open farmland, swamps, and the Potomac River. By contrast, Baltimore, only forty miles away, had already mushroomed into a city of more than twenty-six thousand and would grow to nearly fifty thousand within ten years. Maryland's principal seaport, Baltimore was firmly ensconced as the region's dominant economic and cultural force.

That Baltimore furniture makers of the early national period regarded Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria as growth markets, is documented by a number of advertisements. In 1792, Baltimore carver-gilder and cabinetmaker William Farris notified the public that orders for his wares could be placed with "Messrs. Thomas & James Irvine, Alexandria." Twelve years later, "Cabinet Maker" John B. Taylor advertised that he had opened a shop in Alexandria where he had "received from the manufactory of Coleman & Taylor, Baltimore." And in 1805, Finlay and Cook, makers of "FANCY JAPAN & GILT FURNITURE," commenced business on Alexandria's King Street. Finlay was almost certainly associated with the Baltimore fancy chairmakers of the same name.

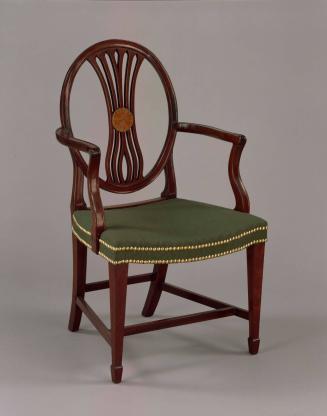

The incursion of Baltimore craftsmen and their products into the District of Columbia probably accounts for the existence of this Alexandria-attributed armchair that is quite similar to a number of contemporary Baltimore-made chairs (see Maryland Historical Society acc. XX.4.183). The CWF chair descended in the Green family of Alexandria and is from the same shop that produced an identical set of chairs first owned by Richard Bland Lee at Sully plantation in adjacent Fairfax County (MESDA research file 6972). While it is possible that the Green and Lee chairs were merely imported into the Alexandria area from Baltimore, it is important to note that both sets differ in several ways from known Maryland chairs of this pattern: the Alexandria chairs have shallower seats; their diagonal corner braces are set at an uncommonly oblique angle; and their backs are considerably narrower at the base, giving the shield form a rather distinctive shape. There were at least nine cabinet shops operating in Alexandria during the 1790s, and these chairs may represent the work of one of them.

Among the most interesting aspects of the Green family armchair is that it received an in-use alteration early in its history. The piece began life as a side chair but was converted to armchair form about 1825. In the process, the front legs were replaced in order to provide the pedestal bases upon which the arms rest in typical early Empire fashion. Evidence of that alteration includes the slight deviation between the profile of the beading on the arms and that on the back assembly, a difference between the finish history of the arm and front leg assembly and that of the rest of the chair, and the interruption of several original tack holes at the ends of the front and side seat rails where they join the front legs. The early date of the change is indicated by the convincing wear on the chair's front legs; the fact that X-rays revealed fragments of hand-filed screws in the joints between the arms and the stiles; and the shaping and design of the arms and their supports that relate to Empire seating furniture of the 1820s and 1830s.

The nineteenth-century owners of this chair deemed it entirely appropriate to adapt their older furniture to fit their changing needs. Such changes were especially convenient in this case since the Greens were a family of cabinetmakers who for several generations between 1817 and 1887 ran a prosperous Alexandria furniture business. That other older furniture was altered in the South Royal Street shop of James Green (1801-1880) is strongly suggested by the archaeological discovery of furniture parts from the 1790s beneath the rubble of the 1827 fire that destroyed the building.

The back design for the Green family chair was also popular in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, where it was usually ornamented with inlays instead of carving. Artisans in both the Chesapeake and New England were clearly inspired by plate 5 in Hepplewhite's 1794 CABINET-MAKER AND UPHOLSTERER'S GUIDE. In fact, the Green and Lee chairs follow that illustration almost line for line. This reliance upon British design sources by artisans working in post-Revolutionary America was quite common and reveals the deep cultural ties that continued to exist between Britain and the United States despite the severance of their political bonds.

InscribedNone.

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceThis chair and a matching side chair have a tradition of ownership in the Green family of Alexandria, Va. According to Deanne Levison the chair was purchased in Alexandria by antiques dealer E. F. Barta, Route 1, Box 381B, Talledega, Alabama 35160; then by Francis McNary of Savanah, Georgia, in the mid 1980s; then by Deanne Levison of Atlanta; then by Kelly Schrimscher, the last private owner.

1790-1815

1805-1815

ca. 1760

1811

1785-1800

1745-1765

1765-1775

1800-1815

1745-1760

1790-1810

1780-1800