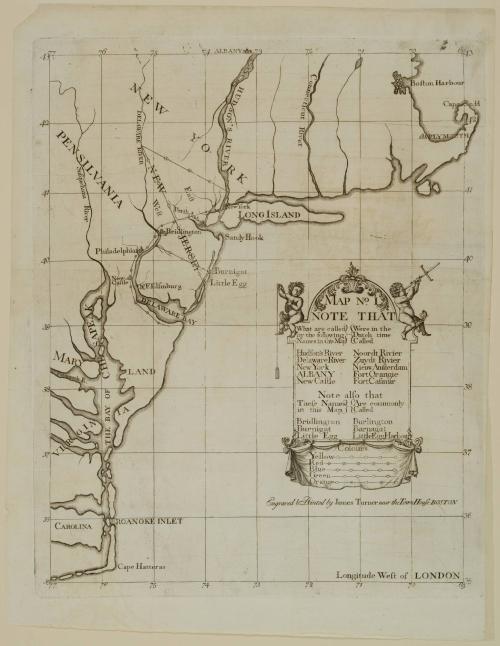

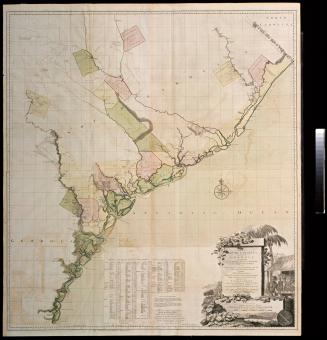

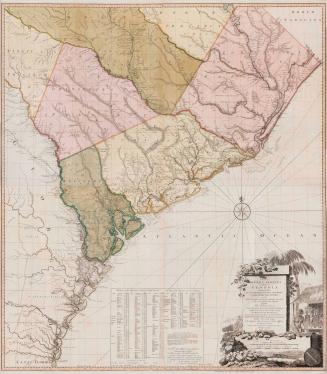

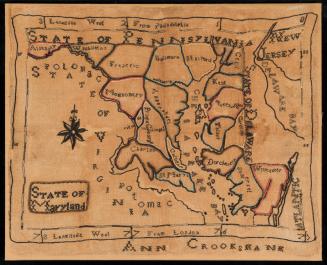

New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina (no title)

Date1747

Cartographer

Lewis Evans (ca. 1700-1756)

Cartographer

James Alexander (1691-1756)

Engraver

James Turner (1722-1759)

Publisher

James Turner (1722-1759)

MediumBlack and white line engraving on laid paper

DimensionsOverall: 15 3/4 × 12 5/8in. (40 × 32.1cm)

Credit LinePurchased with funds from Anna Glen Vietor in memory of her husband, Alexander O. Vietor.

Object number1992-29

DescriptionThe center right cartouche reads: "MAP N.o I/ NOTE THAT/ What are called/ by the following/ Names in this Map/ Were in the/ Dutch time/ Called/ Hudson's River Noordt Rivier/ Delaware River Zuydt Rivier/ New York/ Nieuw Amsterdam/ ALBANY Fort Orangie/ New Castle Fort Casimir/ Note also that/ These Names/ in this Map/ Are commonly Called/ Bridlington Burlington/ Burnigat Barnagat/ Little Egg Little Egg Harbour."Below is a key indicating how the maps were to be colored.

The text below the cartouche reads: "Engraved & Printed by James Turner near the Town House BOSTON"

Label TextThis map of New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina was one of three prepared by the Crown to support its case against settlers who claimed rightful title to land in Newark, Elizabeth, and adjacent territory in New Jersey. The controversy began in March 1664 when Charles II conveyed all of the land between the Connecticut colony and the Delaware River to the Duke of York, the future James II, disregarding the fact that portions of the territory had been settled by Dutch, Swedes, and Finns. The Duke of York sent Colonel Richard Nicolls to capture the Middle Atlantic colonies, and by May this region was under English rule and Nicolls was appointed governor.

The Duke of York subsequently granted the New Jersey proprietary to John, Lord Berkeley, and Sir George Carteret. Before Nicolls learned that New Jersey had been granted to Berkeley and Carteret, he gave the settlers living in the area of Elizabethtown permission to purchase titles to their lands from the Delaware Indians. Nicolls's actions led to years of litigation over who actually possessed title because the settlers claimed possession based on their Indian deeds and the colony maintained that the lands belonged to the proprietorship. The dispute led to A Bill in the Chancery of New-Jersey. The petition, drafted for the Crown against settlers who maintained they had rightfully purchased their land from the Delawares, was introduced to the Council of Proprietors in 1745. James Alexander, lawyer, merchant, surveyor general for both East and West Jersey, Council member in New Jersey, and attorney general in both New Jersey and New York, prepared the document. Alexander carefully researched the land conveyance records pertaining to the territory to show that the land rightfully belonged to the proprietors rather than to the settlers.

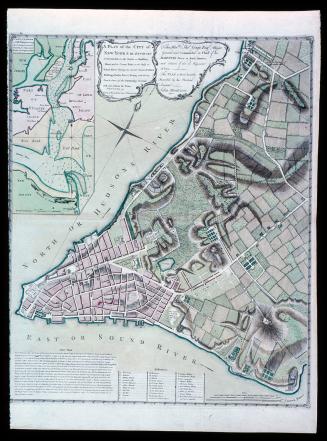

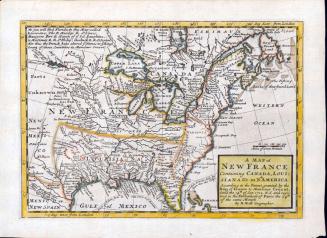

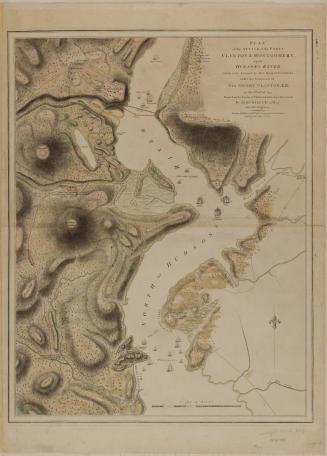

In 1746, Alexander arranged to have two hundred fifty copies of the bill printed. Alexander prepared three maps illustrating the areas in dispute to be included with the bill as hand-drawn inserts by Lewis Evans. They included a map of the East Coast from the Outer Banks of Carolina to Boston, a map of north and central Jersey, and a depiction of property boundaries between Cushetunk Mountain and the Rahway River north of the Raritan in the Elizabethtown tract. The map illustrated in this entry established the geographic context for the dispute. Noted within the text of A Bill in the Chancery of New-Jersey was the fact that it was "copied from part of Popple's large Map of the English Colonies in America, except the red, blue, green, and yellow Colours, and the Notes, which are added . . ."1

Despite Alexander's initial conclusion that the maps "could not be had in this country otherwise than by hand," six months later, he commissioned James Turner to engrave them on copper.2 Ultimately, this proved to be much more costly than Evans's hand-drawn copies would have been. Alexander's accounts for producing the bill indicate that £58.4.7 was spent to procure forty sets of the printed maps. The final cost of £295 for the pamphlet far exceeded the initial estimates. Despite Alexander's careful research and preparation, the controversy was not resolved until after the Revolution.

1. James Clements Wheat and Christian F. Brun, Maps and Charts Published in America Before 1800: A Bibliography (New Haven, Conn., 1969), entry 294.

2. Miller, "Printing of the Elizabethtown Bill in Chancery," p. 10.