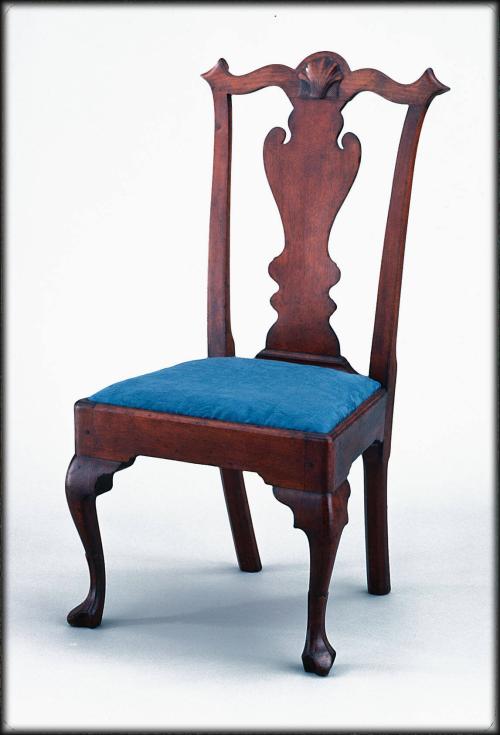

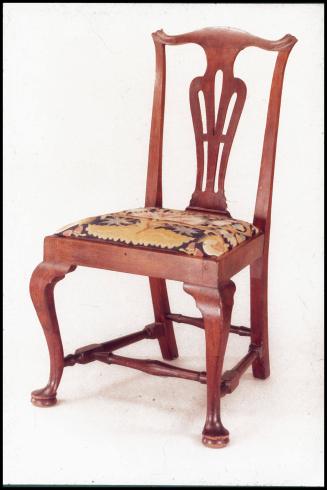

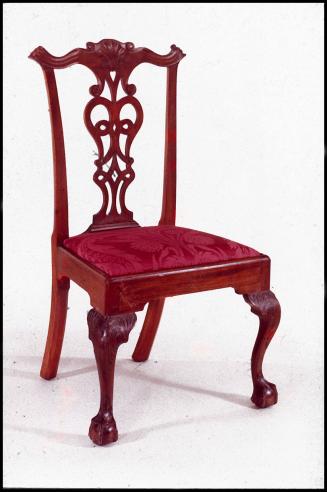

Side chair, splat-back

Date1755-1770

MediumBlack walnut and yellow pine.

DimensionsOH: 40 3/4"; OW: 20 3/4"; SeatD: 16 1/4"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1992-131

DescriptionAppearance: serpentine crest rail with voluted ears, carved central shell, and scratch-beaded edge; stiles with flat, beaded edges and rounded backs above seat rail and heavy chamfering below seat rail; unpierced, vase-shaped splat, molded shoe; front and side seat rils with inset quarter-round molding on upper edge and shaping on bottom; cabriole front legs with "stockinged" trifid feet; cyma-shaped knee blocks flanking front legs; upholstered trapezoidal slip-seat; no evidence for original show cloth. Construction: stiles tenoned into crest rail and pinned; splat tenoned into shoe and crest rail; shoe glued and nailed to rear seat rail; seat rails tenoned into legs and stiles, double- or straight-pinned, and side rails through-tenoned at rear; two-piece, vertically grained, triangular blocks glued and nailed into corners of seat frame; knee blocks glued and nailed to front legs and adjacent seat rails; slip-seat frame mortised and tenoned.

Materials: Black walnut crest rail, stiles, shoe, seat rails, front legs, knee blocks, and joint pins; yellow pine slip seat frame and corner blocks.

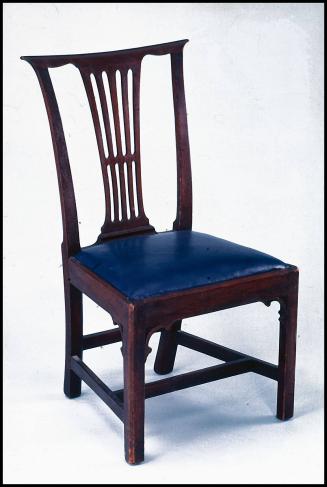

Label TextDuring the quarter-century before the Revolution, British furniture and furniture makers were important sources of inspiration for many cabinetmaking communities in eastern Maryland, just as they were for craftsmen in the lower half of the Chesapeake Bay region. This influence is particularly evident in long-established towns such as Annapolis, where British-born artisans and those trained by them made furniture that closely mimicked contemporary British cabinet wares in proportion, decoration, and construction.

Unlike their counterparts in the lower Chesapeake, some towns along the upper reaches of the Bay were also considerably influenced by craft traditions from Philadelphia. Located less than fifty miles from Maryland's northern border, Philadelphia was then one of the largest English-speaking cities in the world and its economy was a potent force in much of the surrounding region. The city supported a huge furniture trade that trained substantial numbers of cabinet- and chairmakers, many of whom sought employment in nearby areas of eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and eastern Maryland. In the process, these journeymen transplanted Philadelphia style and technology to a host of new locales.

Baltimore is among the best-known examples of this phenomenon. A young and relatively small city with few established craft traditions, its embryonic cabinet trade was dramatically affected by the arrival of Philadelphia cabinetmakers Gerard Hopkins (w. 1767-1800) and Robert Moore (w. 1770-1784) in the late 1760s. Within a few years, a substantial portion of Baltimore-made case and seating furniture was nearly indistinguishable from that produced in Philadelphia.

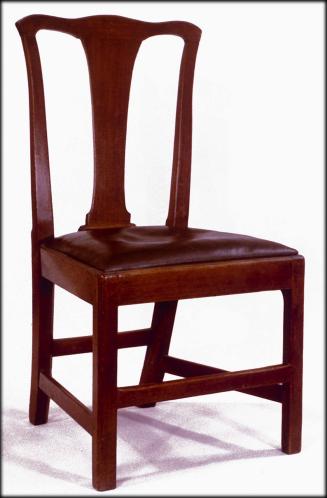

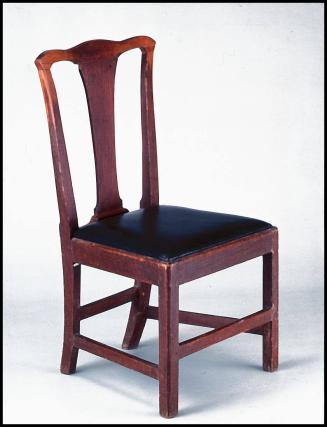

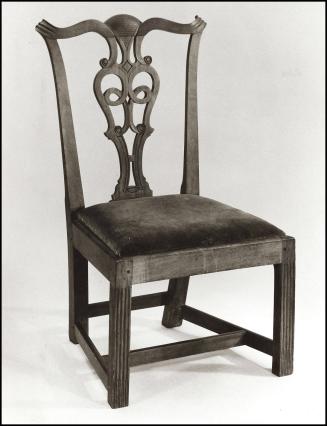

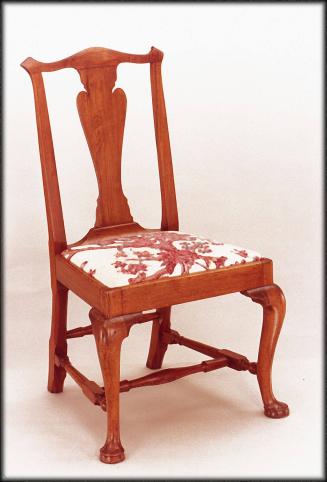

Philadelphia's impact on furniture from some other eastern Maryland towns was equally strong, as demonstrated by the present chair. The serpentine crest rail with a carved scallop shell, relatively deep seat rails, trifid feet, and heavily chamfered curved rear legs are all common to Philadelphia work. Structural components also follow Philadelphia models. The joints are secured with large pins, the knee and corner blocks are fastened with pairs of wrought nails, and the side seat rails are tenoned through the rear legs or stiles. Only the shallow quality of the shell carving, the upward thrust of the ears, and the scratch beading on the crest rail and stiles indicate strong connections to Maryland chair-making conventions.

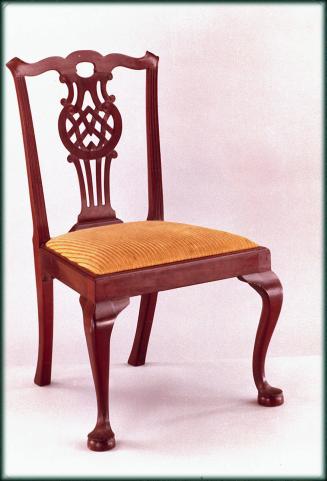

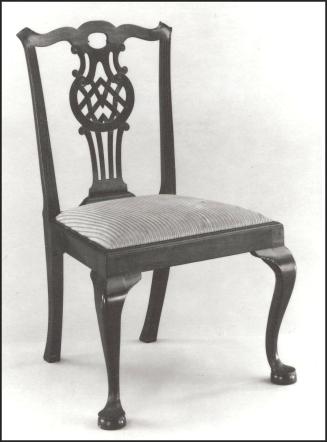

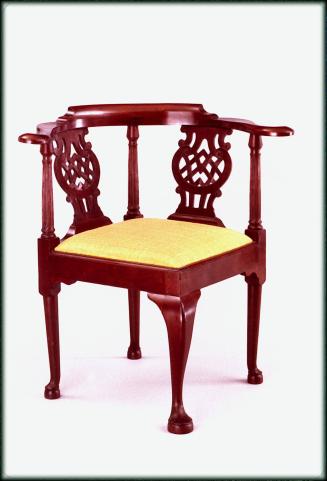

So compelling is the list of Philadelphia workmanship represented by this chair that a Philadelphia or Delaware valley attribution would be a matter of course were it not for the fact that the chair belongs to a group of strongly related pieces with histories of ownership in and around Georgetown, Maryland (now within the District of Columbia). The CWF chair is from a well-documented set originally owned by Allen (1736-1803) and Ruth Cramphin Bowie (1742-1812), wealthy planters who resided at The Hermitage in Montgomery County, a few miles outside Georgetown. Francis Scott Key (1779-1843), a longtime Georgetown resident, once owned a black walnut and yellow pine armchair made by the same artisan. The carving on the crest rail, legs, and feet of the Key chair are identical to those on the Bowie example, and both splats were cut from the same template (collection, Henry Ford Museum). All of these details, including the use of the splat template, are repeated on another, more elaborate, armchair that incorporates shell-carved knees and a pierced splat. Now in the collection of Dumbarton House in Washington, D. C., this third chair was owned by the Peter family of Georgetown from the mid-eighteenth century until the 1990s. The combination of production in a single shop and ownership in or near Georgetown strongly indicates that all of these pieces were made there.

Formally established in 1751, Georgetown was situated at the farthest point of navigation on the Potomac River, just below the falls. Like other fall-line towns in the Chesapeake region, it became an important market center and point of export for tobacco and grain during the second half of the eighteenth century. Georgetown was annexed into the new District of Columbia in 1791, but its economy remained far stronger than that of the newly established capital city for years afterward.

While much is known about Georgetown's furniture trade in the early national period, little has come to light regarding the city's cabinetmakers in the late colonial era. There are no clues as yet to the identity of the artisan who produced the CWF chair and the related examples. It is likely, however, that he was not merely a copier of imported Philadelphia chairs. Instead, the close familiarity with Philadelphia structural and stylistic details apparent in his work suggests that, like Hopkins and Moore in Baltimore, the unidentified Georgetown artisan actually trained in Philadelphia before moving to Maryland. Similar patterns of migration in the decades after the Revolution quickly blurred the once distinct lines that demarcated regional stylistic differences during most of the colonial period.

InscribedThe rear of the slip-seat frame bears the penciled signature "A. B. Davis" for Allen Bowie Davis, who owned the chair in the nineteenth century.

MarkingsFront seat rail stamped "II"; front rail of slip seat frame stamped "I".

ProvenanceThis chair belongs to a set initially owned by Allen Bowie, Jr. (1736-1803) and his wife Ruth Cramphin Bowie (1742-1812) of The Hermitage, Montgomery County, Maryland. The chairs were later owned by their grandson, Allen Bowie Davis (1809-1889), of Greenwood in the same county. Davis gave at least two of the chairs (as well as a pulpit) to St. John's Episcopal Church, Olney, Maryland, in 1842, noting that the chairs had belonged to his grandfather (Archives of the Maryland Historical Society, Minnie W. Bowie Papers, mss. no. 285). St. John's Church retains two of the chairs while three others descended to Miss Maria Bowie, from whose estate they were purchased by Benjamin D. Palmer in 1963. All three were acquired from Palmer's heir by antiques dealer Sumpter Priddy III in 1992. At that time, one was sold to CWF and the other two to Tudor Place Foundation, Washington, DC.

Exhibition(s)

1760-1780

1760-1780

1760-1775

1760-1775

1750-1760

1760-1780

1760-1785

1760-1785

1760-1775

1760-1780

1765-1790

1760-1790