Card table

DateCa. 1818

Attributed to

William King Jr.

(1771 - 1854)

MediumMahogany, cherry, black walnut, white pine, and yellow pine

DimensionsOH: 28 1/2"; OW: 36"; OD: 18"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1994-106

DescriptionAppearance: Rectangular card table with folding top (square when open) with cross banded mahogany around perimeter of top; top swivels on frame to open revealing well inside proper left half of table frame; playing surface is covered in broadcloth (original); rectangular skirt with rectangular raised panels at center of front (horizontal) and at each corner (vertical); ring turned pendants with acorn drops at each corner; urn shaped pedestal base with carved leaves supported by four saber shaped legs carved with leaves and reeding on brass paw castors.Construction: On the top, the lower leaf is bolted through a medial brace and pivots to open. The bolt is held in place by a metal plate that is inset and screwed into the underside of the lower leaf. The lower leaf is composed of five pine boards with mahogany batten ends and a full length mahogany batten on the back edge with a single central tenon that fits into a reciprocal tenon on the back edge of the upper leaf. A rectangular strip of wood is nailed to the lower leaf's underside as a stop. The top of the upper leaf is veneered. It has the same construction as the lower leaf although the number of pine boards is hidden. The playing surface of both leaves is of broadcloth framed on three sides with mahogany veneer. Half-round mahogany molding is nailed and glued to the outside edges of the leaves.

On the frame, the front and back rails are dovetailed to the side rails. The front and side rails are veneered and have a beaded molding nailed to the underside edge. All rails have a thin strip of veneer nailed to the top edge. Unembellished rectangular tablets have been applied to the center of the front rail and the corners. A wide and thick medial brace is tenoned into the top of the front and back rails. A board is nailed to the brace's proper left side to form one side of the compartment that is uncovered when the top is pivoted. The compartment bottom is nailed to the bottom edge of this board and into rabbets in the front, back and proper left rails. The interior of the compartment is covered with broadcloth. On the proper left side corners, ring turned pendants with acorn drops are set on the beaded molding and thin plinths glued to the underside of the compartment bottom, and dowel tenoned into the rails. On the proper right side corners, pendants are set on the beaded molding and quarter round corner glue blocks, and are similarly tenoned to the rails

On the base, the turned and carved urn shaped pedestal is double tenoned into a board with canted edges and wells for screws that in turn secure the board to the underside of the front and back rails. The four carved saber shaped legs are joined to the pedestal base with sliding dovetails reinforced with an iron spider. The legs are marked for identification on the underside with one, two, three or no inscribed lines. Brass paw casters are screwed to the legs.

Label TextAs the federal government expanded after 1800, the population of the District of Columbia continued to grow and the local cabinet trade followed suit. Although imported furniture from northern centers was still plentiful in the nation's capital, nine full-fledged cabinetmaking shops had been established in "Washington City" by 1820. At least three more thrived in neighboring Georgetown, the Potomac River port annexed from Maryland when the federal District was created in 1791. Responding to the needs of everyone from those who aspired to middle-class status to wealthy foreign diplomats, these shops generated a wide variety of household furniture, some of it quite sophisticated.

One of the leading figures among District furniture makers of that period was William King, Jr. (1771-1854), whose Georgetown shop almost certainly produced this card table and a mahogany sofa and a set of matching side chairs about 1820 (CWF acc. 1994-106 & 1994-137,1-2). A native of Ireland, King immigrated to America with his parents on the eve of the Revolution. According to family records, he served an apprenticeship in the Annapolis, Maryland, shop of cabinetmaker John Shaw (1745-1829). King completed his training in 1792 and almost certainly worked as a journeyman in Shaw's shop for another year or more. By 1795, King had moved to Georgetown, where he established a cabinet business that remained in continuous operation until his death in 1854, an impressive run of some fifty-nine years.

That the community held King’s wares in high regard is suggested by a commission he received--probably in 1817--from the administration of President James Monroe. In order to replace furnishings destroyed by British troops during the War of 1812, King was asked to make nearly thirty pieces of furniture for the recently reconstructed White House. Late in 1818 or shortly thereafter, King delivered a suite of four large sofas and twenty-four fully upholstered armchairs that served as the principal furnishings of the East Room until 1873 (examples of which are now in the White House and Smithsonian collections). Made of mahogany, these pieces were executed in the latest style and may well have been inspired by a suite of carved and gilded chairs purchased for the executive mansion in 1817 from Parisian artisan Pierre-Antoine Bellangé.

Although the White House chairs and sofas represent the only documented examples of King's furniture, nearly a dozen other objects with strong and well-founded traditions of production in King's shop survive in that family. Among them is a mahogany Grecian sofa that is identical to the Smith family example (CWF 1994-137, 1) in dimensions, form, and all ornamentation except for the crest rail, which is reeded rather than carved. Other family-owned pieces with credible early traditions of production by King include two library bookcases, a tall clock, and a number of chairs.

Several undocumented objects can be associated with King on the basis of structural and design relationships. For instance, the rosettes on the arm terminals of the CWF sofa were clearly carved by the same individual who produced the floral panels of the arms of the White House suite. The petals and leaves were laid out and veined in exactly the same way on all the pieces. In similar fashion, the carving on the legs of a card table with a long history in the Bradley family of Washington parallels that on the arms of the White House pieces (CWF acc. 1994-106). The ridges and veins of the carved leaves are arranged identically in both cases, although they are quite different from those on most American furniture of the period.

Although little else is known about King's furniture-making operation, much more has been discovered about his activities as an undertaker. Funeral services and supplies accounted for a significant portion of King's business, as they did for most eighteenth- and nineteenth-century cabinetmakers. King's "Mortality Books," the only part of his shop accounts that survive, record the production of an astonishing 7,141 coffins from inexpensive "stained wood" boxes to mahogany caskets lined with broadcloth, between 1795 and 1854.

The services offered by an experienced cabinetmaker like King did not end with the joinery and upholstery involved in coffin making. One of the most complete accounts of his funeral trade survives in the estate records of Clement Smith, whose widow, Margaret, was probably familiar with King as the supplier of CWF's sofa and matching chairs. At Smith's death in 1839, King provided every mortuary service required by a gentry family. In addition to a "Mahogany coffin lined" and "a case for do.," King billed the estate for the use of his hearse, "horse hire for do.," and the cost of a second horse to walk alongside the hearse. King also arranged for the digging of the grave, paid Washington mason Noble Hurdle for lining it with bricks, brought in workmen to clean the family burying ground, and hired twelve hacks to carry mourners and others from the city to Smith's outlying farm. The total cost of the funeral and related services came to $112.50, about the same price King had charged in 1818 for four of the ornate armchairs he supplied to the White House.

MarkingsThree of the legs are marked on the underside near the feet with chiseled Roman numerals I, II, and III.

ProvenanceThe table was sold at Weschler's auction in 1972 with a history of having been from the collection of Katharine Bradley Heald. According to her executor, the table and other objects probably descended to Miss Heald from Abraham Bradley, First Assistant Postmaster General of the United States, who moved to Washington from Philadelphia c. 1800. Prior to her owning them, they were in the family residence "Bradley Farm", then owned by Charles Bradley, now the site of the Chevy Chase Country Club, Bradley lane and Connecticut Ave., Chevy Chase, MD.

Exhibition(s)

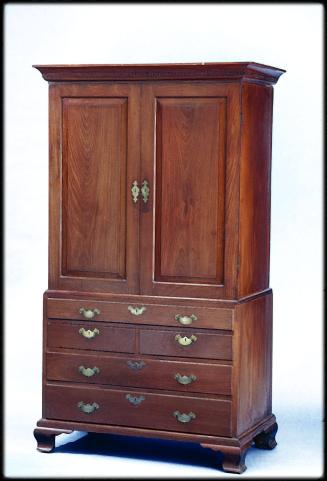

ca. 1775

c. 1762

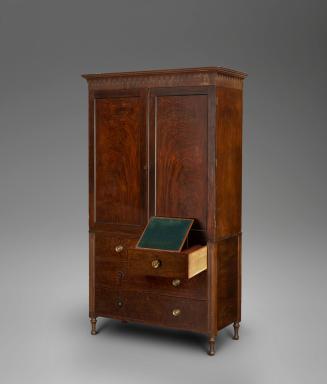

ca. 1810

ca. 1740

Ca. 1810

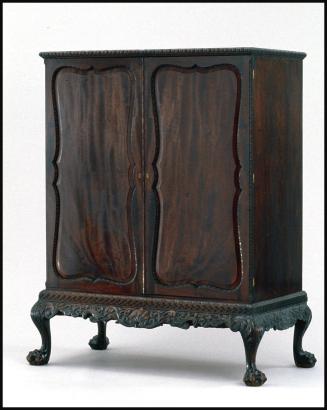

1760-1780

1760-1780

Ca. 1760

ca. 1765

1800-1815

ca. 1740

ca. 1785