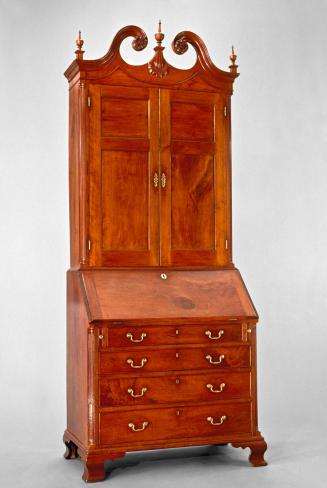

High chest of drawers

Dateca. 1795

MediumCherry and yellow pine.

DimensionsOH: 97"; OW: 44"; OD: 24 1/4".

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1973-325

DescriptionAppearance: High chest of drawers in two sections with broken arch pediment and floral rosettes; urn and spire finials above fluted plinths; urn of central finial carved to resemble a pineapple; carved leafage applied to tympanum below central finial; applied astragal molding on tympanum arching beneath rising curve of arched pediment and continuing around the sides; stop-fluted columns on upper and lower case has three drawers over three larger, all with cockbeaded edges; shaped apron at front and sides; rococo legs with carved shell on knees and ball and claw feet; rear feet are forward facing. Construction: The sides in the upper case are dovetailed to the top and bottom boards in the usual way. The tympanum is tenoned into the stiles that penetrate the top board. The tympanum is further secured to the top board by three glue blocks set inside the case. The carved rosettes are fastened to the tympanum with single screws driven from the rear, while the cornice molding, carved pendant, and swagged astragal molding are all face-nailed. The quarter-columns are flush-mounted to the leading edge of the case sides, and the stiles are nailed and glued to blocks set inside the case. Full-depth two-board lap-joined dustboards are dadoed into the case sides. The drawer blades are tenoned into the case sides. Drawer guides are nailed to the dustboards. Three large glue blocks are set along the front of the bottom of the case at the bottom drawer opening; large wedge-shaped blocks are notched to fit over the outer two blocks and are nailed to the bottom board. The back consists of six lap-joined boards nailed into rabbets along the sides and flush-nailed at the top and bottom.

In the lower case, the case sides, backboard, front top rail, drawer blades, and apron are tenoned into the stiles, which are integral with the legs. The drawer dividers are tenoned into the top rail and the apron. The top board is nailed to the upper edges of the case sides, and the waist molding is nailed to the top board and top front rail. The bottom board is supported by a rail nailed to the case back and by two blocks glued and nailed to each side of the case. Dustboard and drawer guide construction parallels that of the upper case. The quarter-columns are integral with the front stiles. The knee blocks are glued and nailed to the legs and the lower edges of the adjacent horizontal elements.

The drawers are dovetailed in the usual manner. The deeply beveled front and side edges of their bottom boards are set into grooves, while rear edges extend beyond the drawer backs and are secured with nails. Drawer bottoms are further supported by long, widely spaced glue blocks. The cock beading is glued and nailed to the edges of the drawer fronts.

Materials: Cherry case sides, stiles, quarter-columns, legs, knee blocks, tympanum, drawer blades, drawer dividers, apron, drawer fronts, cock beading, all moldings, all applied carving, finials, and drawer stops; all other components of yellow pine.

Label TextFollowing the lead of London furniture makers in the 1670s, joiners in America's northern colonies began to fabricate chests of drawers on tall legs--today's high chests or highboys--as early as the 1690s. With the introduction of more commodious forms like the clothespress and the double chest of drawers, urban British production of high chests largely ceased by the 1730s. However, the form remained a surprisingly persistent symbol of status and good taste in the northern colonies for another fifty years. Artisans in centers such as Philadelphia, Newport, and Boston regularly updated the original form by adding cabriole legs, scrolled pediments, finials, and other embellishments so that late colonial versions of the high chest bore little resemblance to their British antecedents.

The history of the high chest in the coastal South is quite different. Although imported examples probably were available at the end of the seventeenth century, contemporary southern-made high chests must have been rare in what was then an almost wholly rural region. By the second quarter of the eighteenth century, when Chesapeake and Low Country towns became large enough to support their own cabinet industries, a growing number of immigrant British furniture makers had already begun to introduce the newer case forms then replacing the high chest in Britain. Always attuned to changes in British taste, the coastal southern gentry readily abandoned the high chest in favor of more current forms. As a result, numbers of eighteenth-century clothespresses and chests-on-chest survive from the South's eastern domains, but only two fragmentary high chests from the region have been found.

Use of the high chest followed yet another pattern in the southern backcountry. There the form was probably little known until the concept was brought to the area by settlers from eastern and central Pennsylvania, who had begun migrating into western Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas during the second quarter of the century. Traveling in a southwesterly direction through the Shenandoah Valley, these men and women included both recent immigrants from western and northern Europe and the descendants of earlier British settlers. They brought a variety of cultural traditions, some transplanted from Europe and Britain and others assimilated in Pennsylvania. Among the latter was a partiality for the high chest of drawers, which would remain current in the backcountry through the early nineteenth century (see high chest acc. 1930-3).

That high chests produced in the southern backcountry were heavily influenced by Pennsylvania examples is evidenced by the present example. Built in the vicinity of Winchester in Frederick County, Virginia, this late eighteenth-century chest exhibits a number of design details usually associated with high chests made in the Delaware valley twenty years earlier. They include the scrolled bonnetless pediment, finials, and carved rosettes, shell-carved cabriole legs, fluted quarter-columns, and the general arrangement of the drawers. The large scale of the chest is also typical of Delaware valley furniture, as is the presence of dustboards between the drawers, although they were common in eastern Virginia as well.

Despite such strong Pennsylvania influences, the chest's backcountry origin is readily apparent. The placement of an uncommonly large case on small, almost delicate, legs bespeaks a system of proportion quite unlike that used by most Pennsylvania furniture makers. The primary wood is cherry, a backcountry favorite, and the quarter-columns feature arched stop-fluting, an element associated with several shops in the vicinity of Winchester. In place of the exuberant carving found on many Pennsylvania rococo high chests, the pediment on the CWF chest features applied, neoclassically swagged, astragal moldings and a baroque-inspired stylized leaf carving just below the central finial. Finally, the cabinetmaker chose to orient the rear cabriole legs and claw feet toward the front of the case, a novel arrangement with few parallels in mainstream American furniture.

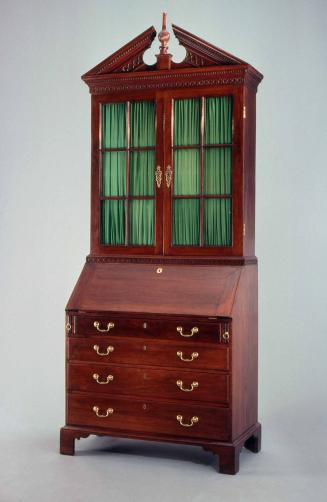

Although he has not been identified, a number of objects are firmly attributed to this maker's shop. Other pieces in the group include a second, virtually identical, high chest (former CWF acc. 1973-206); a desk and bookcase (CWF acc. 1930-68); and a card table (CWF acc. 1987-725). Like the present chest, these pieces descended in the Lupton family of Apple Pie Ridge in Frederick County. From the same shop is a substantial cherry corner cupboard with a late nineteenth-century history in the Kernstown section of Frederick County (CWF acc. 1973-197). These pieces share several structural and ornamental features. Drawer construction and dustboard form are consistent throughout the group, and most of the objects are decorated with the same astragal molding secured by tiny wrought sprigs. The carved ornaments on the pediments of the high chests, the desk and bookcase, and the cupboard were all executed by the same hand, and the turned finials are nearly identical. All of the case pieces also feature fluted quarter-columns or pilasters with the arched stop-fluting noted above.

The Lupton family pieces were first owned by David Lupton (1757-1822), whose father and grandfather moved to the Shenandoah Valley from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in the 1740s. Farmers, Lupton and his father, Joseph (d. 1791), eventually accumulated some 1,700 acres of land in Frederick County. An active member of the local Quaker community, David Lupton also owned both grist- and sawmills. After his father's death, David built a substantial brick house on Apple Pie Ridge. Known as Cherry Row, it was finished in 1794 for the considerable sum of $5,000.8 The Lupton pieces illustrated here were probably ordered then.

According to family tradition, a single artisan or shop was responsible for both the furniture and the interior woodwork at Cherry Row. An inspection of the built-in corner cupboards in the house reveals important similarities between the architectural work and the furniture. The cupboards in the parlor (fig. 118.7) and the chamber above bear many similarities to the freestanding Kernstown cupboard in fig. 118.6. For instance, the pediments on the parlor cupboard and the freestanding model are pitched at the same angle. They also feature fluted Ionic pilasters in their upper cases and flat-paneled Doric pilasters below. The molding sequences from the crown through the frieze and pilasters are very similar as well, although the profiles differ slightly.

Despite these strong connections, there are stylistic differences between the built-in cupboards and the freestanding example. For instance, the parlor cupboard lacks the arched stop-fluting seen on the cherry cupboard and features additional moldings in the tympanum. The capitals on both are composed of the same ornamental elements, but they clearly were executed by different carvers. It is not uncommon to encounter such differences in pieces form a large shop where the master employed several journeymen with different backgrounds. On the other hand, the furniture and the architectural joinery may well represent the products of two different shops whose artisans were working within a precisely prescribed local style.

InscribedUpper case: Top left drawer marked in pencil on top side of bottom "L T" and "3"; top middle drawer marked in pencil on top side of bottom "M T"; top right drawer marked in pencil on top side of bottom "R T". Lower case-Drawer blades for upper and lower drawer. Marked in white chalk moving from left to right "3", "1", and "2"; under side of bottom of lower left drawer marked in white chalk "3"; under side of bottom of middle lower drawer marked in white chalk "2"; under side of bottom of lower right drawer marked in white chalk "1".

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceAccording to Mrs. Allen Bond, a similar high chest to the one purchased from her (1973-206) was sold at Howell M. Bond's sale in the 1950's. Howell M. Bond was her husband's brother. Both Howell and Allen Bond were children of Ann Lupton Bond, daughter of Jonah H. Lupton. Jonah H. Lupton was a son of David Lupton who built Cherry Row on Apple Pie Ridge outside Winchester, Virginia, in 1794-1795. Family history places the high chest sold by Howell M. Bond in the 1950’s at Cherry Row. For a more complete discussion of the interrelated Lupton and Bond families, reference is made to a memo dated February 9, 1995, written by Anne McPherson, a copy of which is in the object file.

Exhibition(s)

ca. 1795

Ca. 1770

ca. 1770

1775-1795

1765-1780

1760-1780

1820-1830

1770-1780

1765-1775

1793-1796

1789

1760-1780