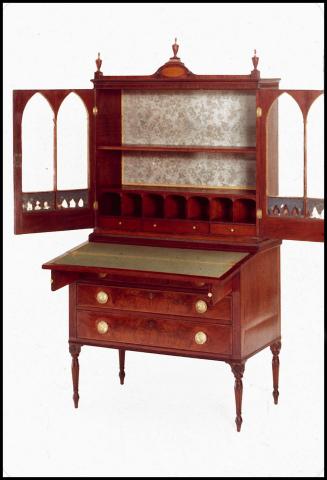

Sideboard

Date1820-1830

MediumMahogany, yellow pine, tulip poplar, and white pine

DimensionsH: 60 1/8" OW: 71 1/8" OD: 24 1/4"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1989-129

DescriptionAppearance: Sideboard with four frontal, disengaged, spiral-turned columns with foliate carved Ionic capitals and carved animal paw feet; two similar carved animal paw feet at rear; columns screen four veneered and cross-banded doors and support three veneered drawers that project slightly at the top; splash board has two flat panels and center mirrored panel, four turned finials, and side galleries with serpentine rails and baluster turned spindles; right door conceals sliding bottle tray with dividers.Construction: The top consists of a solid mahogany board glued to a yellow pine frame. A half-round molding is glued to the exposed edges of this assembly. The splash board consists of a mortised-and-tenoned frame enclosing two flat panels and a central mirror plate, the whole secured to the top board with screws set from below. Plinths are nailed to the tops of the four stiles in the splash board, and a turned finial is round-tenoned into each one. The top rails on the side galleries exhibit two-part construction. The turned balusters are round-tenoned in place.

The carcass consists of a heavy mortised-and-tenoned frame. Openings in the back and sides of this framework are filled with flat panels set into grooves. Interior partitions situated behind the central columns are nailed to the paneled back assembly. A single full-width dustboard supports all three case drawers, extends to near full case depth, and is nailed only to the tops of the two interior case partitions. The outer guides for the right and left drawers are nailed to the carcass side frames, while a pair of guides situated between the center drawer and the right and left drawers are nailed to the dustboard. Kickers for the right and left drawers are nailed to the carcass side frames, and a central kicker for the center drawer is tenoned into the front and back top frame rails. Single shelves in the left and central cupboards rest on ledger strips fastened with nails. A bottle drawer situated at the center of the right cupboard cavity runs between pairs of nailed-on runners and kickers. The freestanding frontal columns are attached to the front of the carcass frame with screws set from behind. Two rear feet are tenoned into the rear ends of the bottom side rails. The right and left front feet are tenoned into projections of the bottom side rails. The central front feet are tenoned into projecting blocks attached to the bottom front rail by unknown means. The cupboard doors consist of panels set into mortised-and-tenoned frames with through-tenoned rails. The case sides, front rails, drawer blades, bottom rails, doors, and drawer fronts are all veneered.

The drawer frames are dovetailed. Their bottoms are beveled and set into grooves along the front and sides and flush-nailed at the rear. The side edges of the bottom panels were originally braced with close-set glue blocks.

Materials: Mahogany splash board frame, galleries, finials, top board, drawer fronts, drawer front veneers, door assemblies, door veneers, feet, columns, applied moldings, and carcass veneers; yellow pine top board frame, mirror plate backboards, bottom case frame, interior case partitions, back assembly, case side assemblies, dustboard, drawer guides, and drawer kickers; tulip poplar drawer sides, drawer backs, drawer bottoms, bottle drawer partitions, case bottom, and interior shelves; white pine panels in splash board assembly.

Label TextAlthough the late neoclassical or Empire style is popularly regarded as a phenomenon of the 1820s and 1830s, the fashion was actually current in many coastal American cities a decade earlier. In Norfolk, then Virginia's largest urban center, records demonstrate that the city's artisans were producing full-blown Empire furniture by 1815. One of the earliest and best documented examples is a mahogany breakfast table with spiral-turned pillars and ambitious acanthus-carved animal paw feet (MESDA accession 3813). Made in 1819 in the shop of James Woodward (w. ca. 1792-1839) for Norfolk resident Humberston Skipwith, it was described on the original invoice as a "large Pillow & Claw Breakfast table" priced at the substantial sum of $45.

Judging from the number of surviving objects, the sideboard was among the most popular forms in the Empire taste generated by Norfolk cabinetmakers. Extant Empire sideboards exhibit a wide range of ornamental options. The example shown here, with its frontal surfaces veneered in highly figured mahogany and an imposing carcass that stands on carved paw feet, is one of the most fully developed. It was made for Harrison Allmand, a wealthy Norfolk merchant. Like most contemporary Norfolk sideboards, this sideboard features a projecting upper tier of drawers supported by four freestanding columns. Instead of the plain veneered columns seen on some other local models, those on the Allmand sideboard are spiral-turned like the legs on the Woodward table and have carved Ionic capitals with guilloche banding and acanthus leaves. Even the splash board is enhanced. Rather than the usual arrangement of three short rails, this superstructure incorporates a tall, paneled, veneered backboard with acorn finials and baluster-turned side galleries. A mirrored center section, which certainly increased the cost of the object, was inserted in order to heighten the visual impact of the silver and glass wares that would have been displayed there.

Despite its embellished exterior, the sideboard's internal construction is surprisingly simple. The carcass consists of little more than a mortised-and-tenoned yellow pine frame infilled with panels, doors, and drawers. Interior supports and compartment dividers are of the most basic kind. Evidence suggests that the sideboard is the product of several artisans who probably worked together in a single large shop. For instance, the carving of the feet clearly represents the work of two different craftsmen. Another shop-related sideboard, originally owned by Senator Willie Person Mangum (1792-1861) of Orange (now Durham) County, North Carolina (a district that often traded with Norfolk), has carving on its columns and carcass by the same hand that carved the columns on the Allmand piece (Historic Stagville accession 81.10.1). While some of the structural details match those on the Allmand sideboard, others differ, again pointing to production in a shop that employed several skilled artisans.

Although the maker of the Allmand sideboard has not been identified, the Woodward shop is a likely candidate. In operation for more than forty years, Woodward's "manufactory" was the city's largest furniture-making and warehousing firm during the post-Revolutionary period, employing "the best Workmen from Philadelphia and New-York, and from Europe" according to an early advertisement. The physical complex eventually incorporated at least two workrooms, a joiner's shop, a counting room, upper and lower ware rooms, and two timber yards. In addition to selling goods made by his employees, Woodward at times expanded his business by retailing furniture from other shops. When Woodward died in 1839, a remarkable array of goods on hand included dining tables, work tables, sofas, bedsteads, "Ward Robes," secretaries, more than two dozen bureaus, sixteen sideboards, and a parcel of "unfinished Work." In all, some 125 pieces of furniture stood ready for sale in the workshops and ware rooms.

Large multidimensional shops like Woodward's became more common in the South's principal urban centers during the 1820s. Only by producing quantities of furniture and warehousing goods from other cabinet shops could these increasingly entrepreneurial artisans compete with the growing volume of inexpensive imports that arrived weekly from northern ports. Many of the smaller, more traditional cabinet shops that had long existed in southern cities were unable to survive in this economic climate, so numbers of their owners eventually withdrew to smaller, more isolated, inland sites where high volume northern exports were not available. In time, even the largest shops in southern port cities found it difficult to compete with the imports. By the 1830s, the southern cabinet trade entered a long decline from which it did not recover until the advent of factory-made furniture in the early twentieth century.

Inscribed"R" (crossed out) and "L" are scratched into the bottom of the left drawer.

MarkingsNone

ProvenanceFor most of its history, the sideboard stood in the Allmand-Archer House on Duke Street in Norfolk. Built in the 1790s, the house was acquired by merchant Harrison Allmand in 1802 and later was remodeled in the Greek Revival style. The sideboard was probably acquired by the Allmand family at about that time. In 1978, Allmand descendants sold the house and furnishings to John Richard, who restored both. Richard sold the sideboard in 1989 to Priddy & Beckerdite of Richmond, Va., who sold it to CWF later the same year.

Exhibition(s)

1815-1830

1790-1805

1765-1780

1797-1800

1815-1820

1700-1730

1800-1820

1815-1830

1790-1800

ca. 1740

1805-1810

ca. 1800