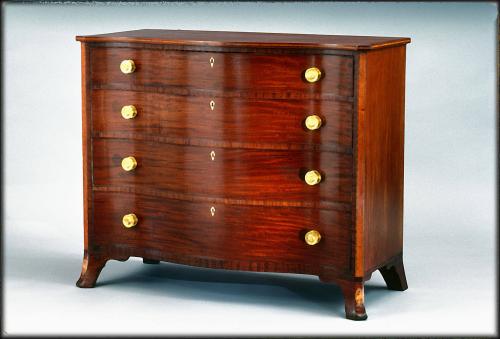

Chest of drawers

Date1790-1805

MediumMahogany, tulip poplar, oak, *sweet gum, *white pine, *red pine, *yellow pine, red cedar, satinwood, *hard maple, and ivory. *=microanalysis.

DimensionsOH: 40": OW: 49 3/8" OD: 22 3/8"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1988-231

DescriptionAppearance: Serpentine chest with canted front corners; conforming overhanging top with complex string inlays; canted corners ornamented with cross-banded satinwood and complex string inlays; splayed bracket feet, those at front conforming to canted corners and ornamented with pictorial inlays depicting conch shells; straight, unmolded lower edges on front and sides of case; four graduated drawers with cock-beaded edges, lozenge-shaped ivory escutcheons, and (originally) center-post stamped brass pulls; reverse of drawer fronts covered with original thin red wash. Construction: The solid top is attached to the case sides on two sliding dovetails. Standard dovetails join the solid case sides to the case bottom. A shaped stile is laminated to the leading edge of each case side to accommodate the out-curving canted corners. The drawer blades are veneered on their front edges. The blade above the top drawer is backed by a pair of front-to-back kickers that prevent the drawer from tilting down when pulled out. The remaining drawer blades are backed by dustboards that are thinner than the blades and stop just short of the back. They are wedged from below by glue strips, some laterally grained, the remainder grained front to back. Pairs of stop blocks are nailed to the upper surfaces of the second, third, and fourth drawer blades and to the upper surface of the bottom board. The case back consists of four beveled panels set within a framework of stiles and rails that are mortised and tenoned but not pinned. The back assembly is nailed into rabbets at the top and sides and flush-nailed at the base. A mitered framework of tulip poplar strips is glued and nailed to the case bottom along the front and sides. Thin mahogany foot brackets are backed with stacked horizontally grained glue blocks, all of which are glued to the tulip poplar framework.

The drawer frames are dovetailed at the corners. Drawer fronts consist of mahogany veneer on horizontally laminated oak cores. Their interior surfaces are coated with a thin red wash. The drawer bottoms are nailed into rabbets at the front and sides, and the resulting joints are covered with full-length glue strips mitered at the rear corners. The rear edges of the drawer bottoms are flush-nailed. Cock beading is glued and nailed to the edges of the drawer fronts. Two small interior drawers, now missing, were originally positioned one above the other and set between a pair of surviving partitions dovetailed into the front and back panels of the top large drawer. A thin dustboard that separated the small drawers is dadoed into these partitions.

Materials: Mahogany top, sides, applied stiles on case sides, drawer front veneers, drawer blade veneers, foot brackets, and cock beading; tulip poplar case bottom and case bottom framework; oak drawer front cores, drawer sides, and stop blocks; *sweet gum drawer backs; *white pine drawer bottoms, drawer blades, dustboards, and back panels; *red pine back stiles; *yellow pine back rails, top drawer kickers, drawer bottom glue strips, and foot blocks; red cedar partitions for the small drawers within the top drawer; satinwood veneer on canted corners; *hard maple complex stringing; ivory escutcheons. *=microanalysis.

Label TextThe majority of colonial Norfolk furniture was made by British immigrants or Virginia artisans trained in the British style. That changed after the Revolution as furniture and furniture makers from New York, Philadelphia, and New England began to arrive in large numbers. Most locally made cabinet wares soon took on a decidedly northern appearance. The shift in taste was facilitated by the fact that few of the city's established cabinetmakers returned after the war. It was reinforced by wartime destruction that had left Norfolk "a vast heap of Ruins and Devastation."

Despite these changes, the Norfolk cabinet trade experienced a minor resurgence of British influence by the end of the century. As illustrated by this surprisingly British-looking chest of drawers, it affected both construction and design. Confined to the work of a few shops, the British revival was due to the arrival of a series of immigrant cabinetmakers shortly after peace was established. Among them were Londoner John Lindsay, who worked in Norfolk from 1785 to 1792, Irishman James McCormick, who came to Norfolk in 1787 after a brief stay in Alexandria, and John Lattemor, a Scottish artisan who appeared the same year. These and other British furniture makers remained in postwar Norfolk only a few months or years, but their collective presence apparently was enough revive a trace of British taste in the local market.

The CWF chest exhibits many of the sophisticated structural details encountered on the best contemporary British furniture. The drawer blades are backed by thin dustboards wedged into dadoes from below with short contiguous blocks whose grain runs side to side like that of the dustboards. Because the grain of the two elements is sympathetically organized, each reacts to changes in temperature and relative humidity by expanding and contracting together. It would have been simpler and cheaper to substitute one long front-to-back strip for the short lateral blocks, but the resulting joint, with woods of opposing grain, would be more likely to generate shrinkage cracks in the dustboards and case sides.

The chest's fully paneled back is also typical of British work. Consisting of beveled panels that float in the grooved edges of a mortised-and-tenoned frame, backs of this kind are often encountered on British and urban southern bookpresses, clothespresses, and other forms with sliding or removable interior shelves. The joined back frame lends tremendous strength to such case pieces, whose functions would normally preclude the presence of fixed internal supports. The presence of a paneled back on a chest of drawers like this one, which has a complete system of supporting dustboards, is structurally redundant and illustrates the extremes to which urban British joinery was sometimes carried. Similar combinations of full dustboards and paneled backs are occasionally found on case furniture from Annapolis and Williamsburg.

The horizontally laminated foot blocking on the Norfolk chest is another example of the best British craftsmanship. Like the laterally grained glue strips beneath the dustboards, the blocks follow the horizontal grain of the bracket faces, allowing the unit to expand and contract in unison. Again, it would have been easier to substitute a single vertical block for the multiple individually cut and glued horizontal ones, but many British artisans and their coastal southern counterparts were willing to forgo the shortcut in favor of a foot with greater structural integrity. Although stacked blocking is often encountered on the straight bracket feet of earlier Virginia furniture, it is rarely found on later splayed or "French" feet like these.

The ample size of the CWF chest of drawers, unusual by American standards, is common in Britain. Six other equally large Norfolk chests representing the work of at least two shops are now known (see MESDA acc. 2985M). All exhibit sophisticated and time-consuming structural details like those noted here. At the same time, the external ornamentation on each piece is restrained and almost severe. Together, these chests suggest that in the face of sweeping stylistic changes, some householders in early national Norfolk still preferred well made but neat and plain furniture of the kind that had set the standard in eastern Virginia cities for decades before the Revolution.

InscribedColumns of ciphering are written in chalk in an eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century hand on the interior of the back panels.

MarkingsNone

ProvenanceThe chest was purchased from Priddy & Beckerdite, Richmond, Va., in 1988. The firm had acquired it the same year from an antiques dealer in Virginia Beach, Va., who had purchased it at a rural estate sale near the North Carolina border in the same jurisdiction.

1765-1780

1775-1782

1820-1830

ca. 1800

1797-1800

1765-1775

1740-1755

1790-1810

1760-1775

1800-1815

1750-1765

1785-1792