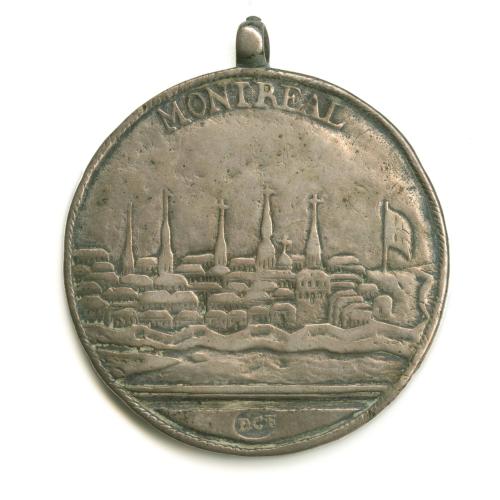

"Montreal" Medal

Dateca. 1761

Maker

Daniel Christian Fueter

(1720 - 1785)

MediumSilver

DimensionsDiameter: 45mm Weight: 344 grains

Credit LineMuseum Purchase, Lasser Numismatics Fund

Object number2015-146

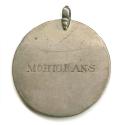

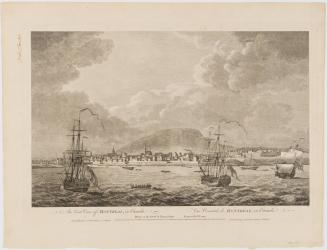

DescriptionCast silver medal with integral hanger. The obverse bears an image of the city's walled skyline along the St. Lawrence River, featuring six church spires and one flag, below MONTREAL. Its reverse was made blank, then engraved with the name and tribe of the Native American it was given to.Label TextOf all the medals produced in the 18th century specifically for Native Americans, the "Montreal" medal is the only one to carry both the name of the individual who received it and that of his tribe. It is also one of the most historic and extensively documented medallic issues of the American colonial period and is therefore of the utmost importance.

With the fall of Montreal on September 8, 1760, Britain, helped by her American colonies, completed the subjugation of French Canada. During this military expedition Sir William Johnson served directly under the General Jeffrey Amherst, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in America. In his capacity as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies, Johnson was in charge of the Native Americans who accompanied the Anglo-American forces participating in this final siege of the French & Indian War. Seeking to reward these loyal warriors for their participation, a collaboration between Amherst and Johnson brought the Montreal medals into being.

Not wanting to endure the time and expense of having medals struck from dies back in England, an American source was sought. Sir William drafted a list of those Indians he wanted to receive medals, and sent it along with General Amherst, who intended to see to their immediate manufacture from his headquarters in New York City. Writing on the first of February the next year, Amherst advised Johnson;

"As an Encouragement to Such as behaved well during the last Campaign, I have, as I mentioned to You, I would, Ordered a Number of Silver Medals to be Struck, representing the City of Montreal with a blank Reverse, On Each of which is to be Engraven the Name of One of those Indians, who, by wearing the same as a badge of Distinction, will, by Virtue thereof have free Egress & Regress to any of His Majesty's Forts, Posts, & Garrisons, so long as they Continue true to his Interests: they are not quite finished Yet, when they are, I shall send them to you, to make a Distribution of them."

The medals were completed by April of 1761, and were further detailed in a report Amherst made to William Pitt back in London;

"I have sent one hundred and Eighty two medals to Sr Wm Johnson, to be delivered to as many Indians, who accompanyed the Army to Montreal, it will please the Indians much, and I trust will have a good Effect. the Expence is not great, the whole amounting to 74 = 6 = 4 Sterling."

At the above price, we can deduce that the medals cost 8 shillings and 4 1/2 pence Sterling apiece, which is a good deal as Amherst says. In other terms, each finished medal cost a little bit less than two silver dollars at the current New York exchange rate. Each medal bears the “DCF” mark of Daniel Christian Fueter, the silversmith who seemingly handled all aspects of the manufacture of the medals from the design to the engraved inscriptions. Since Fueter had emigrated to New York from Switzerland (via London), it is not surprising that his depiction of Montreal on the medal resembles the cityscapes seen on European coins and medals of the period. After the Revolution erupted and the focus of the war came to New York in 1776, Fueter headed back to Switzerland. His son Lewis, an ardent Loyalist, remained in the City and became an accomplished silversmith too.

On the 17th of April, Amherst again wrote to Johnson, the recipient of the only specially-commissioned gold Montreal medal the General ordered, then at his home "Fort Johnson" near Albany;

"I send you by Capt. Minnett 182 Silver medals for that Number of Indians who were under your Command On Our Arrival at Montreal. Each medal has a Name Inscribed on it, taken Exactly from the List which you gave me in Canada, according to the Enclosed Copy. The Names of the Ashquesashna Indians were left blank, but, I imagine, it will not be difficult to find a person to add the Names to them, which I must beg the favor of you to have Inscribed on the medals, And that you will please to Deliver the whole, as a mark of the King's approbation of their faithfull Services, which they are to wear, as a proof of His Majesty's satisfaction of their Zeal and Bravery; And that they may be distinguished by this Token, whenever they shall Come to any of the Forts or Posts, from those unworthy Indians, who so shamefully abandoned the army after we left Oswego. Amongst these medals, there is One for Silverheels who is at present at Carolina, and I don't know but there may be more Indians there, who are Included in the List. I Enclose One of these medals in Gold, which I beg your Acceptance of; and that you will permit me to say, no one has so good a right to it as yourself; for I am convinced those Indians that did Accompany the Army were Induced to it from the proper Care, and good Conduct you shewed towards them."

It is clear from Amherst's words that the medals represented a reward in excess of the object itself; they were meant as a good conduct passes, which is why they bore the owners name and tribe on the reverse. The reason for this additional purpose to the medal has to do with the exemplary behavior of these 182 warriors. As the force bound for Montreal was preparing at Oswego in the summer of 1760, over 500 Natives decided to abandon the expedition and left. Those who remained with the expedition and participated in the taking of the city truly proved their worth to the Crown Forces and deserved this extra privilege. One is left wondering if those warriors who headed for home instead of Montreal regretted their decision once they saw Montreal medals around the necks of others as they freely entered secure forts and trading posts.

Because of unrest in the Detroit area, Sir William, ever industrious in the promotion of good relations with the Natives, left on a diplomatic mission seeking to secure additional allegiances to the British Crown. Along his rout west, Johnson took the opportunity of presenting some of the medals, and wrote of one such distribution. Taking place at Oswego on July 21,1761 in front of forty Onondaga “Sachems & Warriors,” Sir William handed out 23 medals and recorded his address at the presentation ceremony;

“His Excellency General Amherst being desirous to shew his regard to merit, having taken notice of the behavior of all those Indians who, as became faithfull Allies continued with the Army after the reduction of Fort Levis & proceeded with them to Montreal, has thought proper to have Medals struck in Commemoration there of, to be by me distributed amongst them as an honourable mark of his approbation of their Conduct, & which will intitle the Wearer to some provisions, & good treatment at all the posts — It is with pleasure I now present you with those ordered for your Nation, and I flatter myself that you will on all occasions manifest the same zeal and attachment to his Majesty's service which hath intitled you to this publick mark of distinction."

Other correspondence from Sir William shows that he intended to distribute each of these medals personally, showing how important he felt their significance was. With some of the named recipients moving as far away as the Carolinas, it took some time for the distribution to be completed, if it ever was.

Colonial Williamsburg's example of the Montreal medal was presented by Sir William Johnson to a warrior named Songose of the Mohicans, a tribe which lived along the Hudson River in the Albany area. Being a member of a neighboring tribe, Songose may have received his medal from Sir William at his home Johnston Hall, still standing in Johnstown, NY.

Evidence gleaned from this medal suggests that it left Songose's possession for one reason or another and became the property of another. The new owner of the Montreal medal saw fit to crudely erase Songose's name from the top of the reverse, but enough of the inscription remains for the name to be fully legible. Sometime afterwards, the medal was lost or discarded in the wilderness north of Albany.

A local newspaper, the “Daily Saratogian,” heralded the recovery of Songose's medal on September 25, 1875, as being found while gardening in Ballston Spa, NY by Mr. Patrick Kelly. In reporting the lucky find of a few days earlier, the paper offered an explanation as to why the medal ended up in the ground at what was to become a garden. Even before the below appeared in print, Kelly had sold Songose’s Montreal medal to a local collector;

“On the 21st instant a Mr. Kelly, residing in the east part of the village on a new street opened a few years ago through what was known for many years as Smith’s woods, discovered a few days since, while digging in his garden an oval piece of silver. Taking it into his hands he discovered it to be silver. Carefully cleaning it, it was found to be a silver medal which undoubtedly had lain there for three quarters of a century. It is about an inch and a half in circumference and bears on the obverse side a view of the city of Montreal with St. George’s cross floating above the citadel. Beneath this the word “Montreal” and the letters “D.C.F.” On the other side of the medal are the word “Mohicrans,” in Roman capitals, and in script above it the name “Son Gose.” From there legendary inscriptions it would appear to be one of the medals given to the Mohegan Indians by the British government for their services in the revolution. “Son Gose” was probably a chieftain or warrior of that tribe. How it should have been lost in the place where it was found is explained by Hon. G. Scott, who remembers his father’s telling that the Indians had a summer encampment in Smith’s woods every year down till after 1800. The relic may have been lost by the rude warrior or one of his descendants……...The tract where it was found has never been plowed until the past two or three years. The ancient relic was purchased of Mr. Kelly by Joseph E. Westcot, who is now its fortunate possessor. Its weight is a trifle less than the American silver dollar.”

Joseph Westcot (1827-1902) sold the medal to Mr. Elsey Hallenbeck (1859-1933), a collector in Schenectady, NY, in 1902. Songose's medal was in Hallenbeck's possession the next year when it was discussed and illustrated in William Beauchamp's “Metallic Ornaments of the New York Indians.” Published as Bulletin 73 by the New York State Museum in Albany, the accompanying plates were the often-crude drawings of the author. Illustrating only the reverse of this medal, for the sake of clarity Beauchamp drew the engraving of Songose's name as much more bold than appears in reality.

Hallenbeck sold the medal to Charles Arthur Laframboise (1866-1916) of Montreal, an obscure early 20th c. collector known for the loan of a number of great medallic rarities to the Chateau de Ramezay and listed in their 1910 catalogue. From there it went to a Robert Brule, who sold it along with other items from Laframboise’s holdings to New York collector John J. Ford, Jr. in June of 1961.

While six genuine Montreal medals were reported early in the 20th century, the whereabouts of only four of the original 182 are known today. Songose's Montreal medal at Colonial Williamsburg is one of only two located in the United States.

Betts-431

Beauchamp-388

InscribedAcross the center of the reverse MOHICKANS is engraved in bock capitols. The largely erased name SONGOSE is engraved in script at the top, and is bisected by the hanger. Only the "S" in the name is capitolized.

MarkingsThe mark of Daniel Christian Feuter appears struck into the exergual area of the obverse. His initials DCF are raised within this ovoid mark.

ProvenanceFrom the Stack's sale of the John J. Ford, Jr. Collection, Part XVI, October 2006, Lot 47. Found in 1875 by Mr. Patrick Kelly while gardening at his Ballston Spa, NY home. Kelly quickly sold the medal to Joseph Westcot, who sold it to Elsey Hallenbeck of Schenectady in 1902. From Hallenbeck it went to Charles Arthur Laframboise of Montreal, and thence to Robert Brule. Brule sold it along with other medals he had obtained from Laframboise to John J. Ford, Jr. in June 1961. Since then it was auctioned by Stack's Bowers twice; once as cited above and again in 2009.

ca. 1733

1860-1880

January 28, 1778

Late nineteenth century

1800-1827 (compiled); some 1726

Ca. 1650 (Textile)

1773-1774

1950-1965

1824-1828 (range of the entires in the album).

c. 1762