Dining table, gateleg

Date1700-1730

MediumBlack walnut throughout.

DimensionsOH: 27 1/8; OW: (open) 47 1/2; OW: (closed) 18 3/8; OD: 53 3/4.

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1966-487

DescriptionAppearance: Oval gate-leg dining table; ball-and-ring turned legs and end stretchers; other rails and stretchers rectangular in section and with molded edges.Oval top in open position; center section of top and each leaf made of two pieces; center section supported by four turned legs with one turned stretcher at each end and one stretcher square in section at each side (quarter round molding on two upper edges); one gate at each side with turned inner support and turned leg; all feet of one half ball shape.

Construction: Pairs of wooden pins along the joint lines in the two-board top and leaves suggest that they are butt-joined and secured with concealed tenons. The leaves are rule-joined to the top and move on iron hinges. Wooden pins hold the top to the frame. The rails are tenoned into the legs and fastened with single pins, while the stretchers are similarly joined and secured with double pins. The gate leg stiles swing on round-tenoned ends at the top and bottom, and the rails and stretchers are double pinned. When closed, the legs on the gate assembly half-lap into open mortises on the rails and stretchers.

Label TextA number of early southern gateleg tables are known. Unlike some of their northern counterparts, however, few can be associated with specific local shop traditions. This imbalance is due largely to the fact that the South's agrarian economy delayed the development of urban furniture-making centers until about 1725, by which time the gateleg form was going out of fashion. Records and surviving objects demonstrate that specialized artisans like turners and joiners were working in settled areas of the South throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, but in the absence of large towns, few were able to earn a full-time living by the exclusive practice of the woodworking trades. Moreover, the destruction of property wrought by the Civil War, Reconstruction-era poverty, and a hot, humid climate have sharply reduced the survival rate of furniture from this earliest period, thus making the recognition of shop groups even more complex.

As is the case with other furniture forms, most early gatelegs from Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas mirror British prototypes. The present black walnut table is no exception. With ball-and-ring turnings on its legs and end stretchers, the table exhibits an ornamental pattern found on many seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century British tables, chairs, benches, and stools. Given their shared design sources, it is not surprising that New England interpretations of the same general turning model are also known.

The CWF table has no known history prior to its ownership by a Richmond collector early in the twentieth century, but several of its features suggest production in eastern Virginia. A black walnut table with similar, albeit heavier, turnings was sold by a Richmond antiques dealer in the 1930s (MESDA research file 5303). Like the present example, it displays well-worn ball feet, an oval top with no decorative molding on the edge, turned end stretchers, and end rails with heavily beaded lower edges. Although not by the same hand, the two objects are similar structurally. The design of the hinge legs and the way they are attached to the frame are virtually identical. The second table likely represents a more expensive product since its side and lower gate stretchers are turned rather than plain and it has a large drawer at one end.

While the baluster-form legs and stretchers seen here represent a widely popular design motif, the distinctive flared division between the balls and rings on the legs of this table may represent a more specific regional turning tradition. A similar detail appears on the legs of a black walnut gateleg table that descended in a family from Westmoreland County on the Northern Neck of Virginia, and closely related baluster turnings survive on architectural fittings at the circa 1706 Yeocomico Church in the same county. The general relationship of the CWF table to these Northern Neck examples supports a tentative attribution to that area.

InscribedNone.

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceThe table was owned by Dr. R. A. Patterson of Richmond, Va., in the early twentieth century. It was bequeathed to his daughter and was later in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond C. Power, who sold it to CWF in 1966.

Ca. 1725

1715-1740

1770-1790

1710-1740

1710-1740

1690-1730

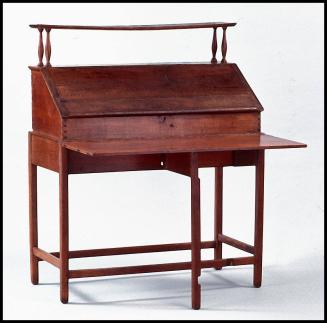

1800-1825

1700-1730

1650-1700

1760-1780

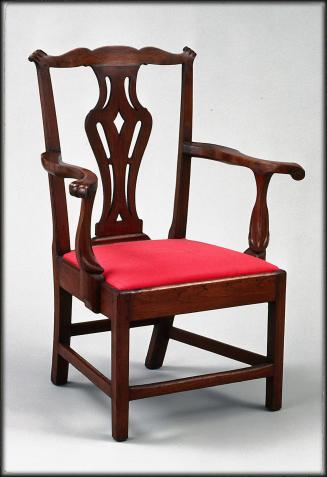

1755-1775

1815-1820