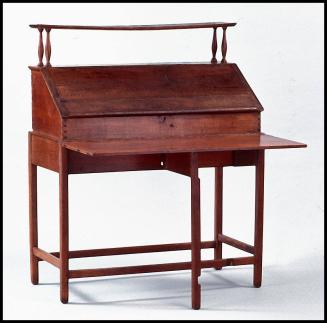

Tea table

Date1720-1730

MediumBlack walnut throughout (juglins negra, by microanalysis).

DimensionsOH: 27 1/2"; OW: 26 3/8"; OD: 21 1/2"

Credit LineGift of Col. & Mrs. Miodrag R. Blagojevich

Object number1976-429

DescriptionAppearance: Rectangular tea table with applied top molding; four turned legs and turned box stretchers; heavily shaped skirts.Construction: The top consists of three butt-joined boards and is heavily rounded on its lower edges. Four black walnut butterfly cleats once connected the top boards. Oxidation levels and workmanship suggest that they were first-period construction. Unlike most later Virginia tea tables, the edge molding is not set in a rabbet but is flush-nailed directly to the top; wrought T- or L-head sprigs are driven in from above and at an angle from below. Wooden pins originally secured the top to the frame. The rail tenons are double-pinned; those on the stretchers are fastened with single pins.

Label TextThis eastern Virginia tea table is among the earliest southern survivals of the form. The blocked-and-turned legs and stretchers were produced on a lathe and the scalloped rails were laid out with a rule and compass and sawn to shape. The frame was mortised and tenoned together, the joints secured with wooden pins, and the top pinned to the frame. European and American artisans used the same techniques to build joint stools and small tables in the seventeenth century, although several of the stylistic details on this table suggest that it was made after 1700. For instance, the shaping of the rails mirrors that on several eastern Virginia tables of later date, among them the end rails of a late baroque dining table found in Isle of Wight County (MESDA research file 3893). With its rectangular top, straight-turned legs, and pad feet, the Isle of Wight table was probably not made before the 1740s.

Columnar legs much like those seen here occur on southern dining, tea, and side tables with local histories in areas from eastern Maryland to northeastern North Carolina. Although the CWF table has a vague Virginia provenance, it is difficult to narrow the attribution any farther given the broad use of the columnar leg in the Chesapeake. Such turnings were also employed on a great many early British tables, and it is likely that the design was introduced into many coastal southern woodworking centers at an early date via both imported furniture and immigrant turners.

Despite its well-proportioned architectonic legs and shapely rails, evidence on the underside of this table reveals production methods that point to execution by a joiner rather than a cabinetmaker. Adze marks, splits, and deep tear-outs on the inner surfaces of the rails strongly suggest they were made from black walnut that was first hewn or split into rough billets and then worked down to the present size, an observation borne out by the varying thickness of the rails. The billet theory is also bolstered by the fact that the rails and each of the narrow top boards were worked from small pieces of wood roughly the same size.

House joiners often made relatively uncomplicated furniture early in the colonial period. A case in point is the altar table at Fork Church in Hanover County, Virginia (MESDA research file 6832). Its turned columnar legs closely match the turnings of the balustrades in the church, and it is likely that the table was produced by the carpenter-joiner who also provided the building's interior woodwork in 1736. The CWF tea table's three butt-joined top boards were originally fastened together with wooden butterfly cleats, a method commonly employed by house joiners in the construction of architectural paneling.

InscribedNone.

MarkingsNone.

ProvenanceJoe Kindig, Jr., who had earlier purchased the table in Virginia, anonymously loaned it to the 1952 exhibition "Southern Furniture, 1640-1820" at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. He sold the table to the donors sometime before 1962.

1710-1740

1670-1730

1795-1805

1770-1790

1700-1730

1735-1745

1749-1753

1775-1790

1800-1825

1700-1730

1765-1780

1740-1760