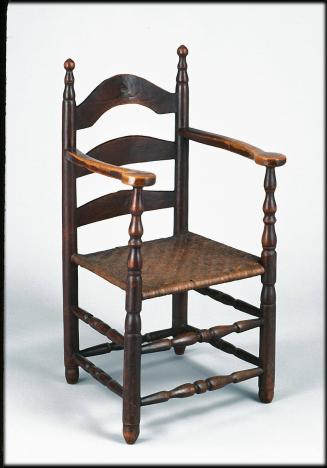

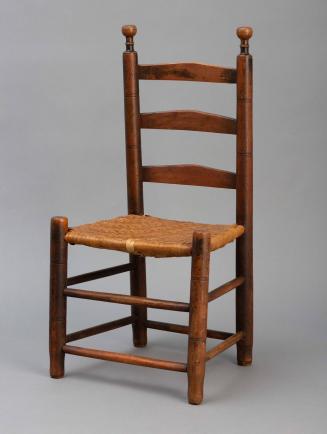

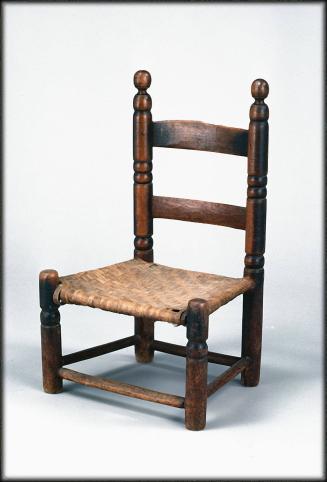

Armchair, banister back

Date1690-1715

MediumBlack walnut (by microanalysis)

DimensionsOH: 45 1/2"; OW: 22"; SeatD: 16 3/4"

Credit LineMuseum Purchase

Object number1953-585,A

DescriptionAppearance: turned arm chair with square curvilinear arms with small, round terminals; midly elongated ball feet (not original); leg posts consist of alternating blocked-and-turned addorsed balusters with a "spool" element just below the seat lists; upper portion of the posts has an elongation of the addorsed pattern with a central hollow, a pattern repeated on all six stretchers (two on each side); rear posts terminate in a 3 1/2" tall club-like finial; arm supports are columnar with plain turned bases and capitals; back consists of two widely spaced banisters that are rectangular in cross section and have a large (1/2") wide cockbead on the outer edge; banisters are set into crest and stay rails of the same design; wide seat lists with rabbeted interior edge were originally square in cross section and enframed a plank seat. Construction: the chair features mortise-and-tenon joinery throughout. All joints are angled to give the chair a backward list. Many of the joints are fixed with two square pins set one above the other.

Label TextThere was a lack of trade specialization in the sparsely populated South until the early eighteenth century. Most woodworkers did not focus on a single occupation but pursued related disciplines like carpentry, turning, and furniture making. As a result, the region's earliest chairs often exhibit a combination of turned and joined work. For example, the posts and stretchers of this black walnut great chair were turned on a lathe, while the frame was secured with mortise-and-tenon joints like those employed by joiners. Turning and joinery traditions were combined to produce the seat as well. Later rounded to accept a woven covering, the seat rails were originally rectangular in section with rabbets cut along their inner edges to accept a wooden seat board. Such inset plank bottoms were generally reserved for turned chairs. Joined chair frames like this one normally featured flush-nailed seat boards that overhung the rails, as on joint stools.

Another unusual feature of this chair is its complex angled joinery, which creates an intentional backward list for greater comfort. Raked backs most often were achieved by sawing angled rear posts out of wide boards or by using off-center or double-axis turning. The maker of this chair may have been unfamiliar with these approaches, especially if he was working in a rural context. Conversely, the angled stance may represent a European chair making tradition that is not recognized now.

Much of the furniture made in the coastal South before 1750 reflects British traditions, but this chair exhibits at least one element associated with French chair design. The upper back is comprised of a large, open frame that offers little support for the sitter. This configuration suggests that the chair was designed for use with a tied-on carreau, or squab; a similar cushion would have been placed on the hard plank seat. Tied back cushions were often employed on French and some other continental chairs in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, but they were rarely used in Britain or America. The tradition may have come to the colonies with Huguenots, or French Protestants, who fled religious persecution in France after the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Large numbers of Huguenots settled in the South, particularly in the Carolina Low Country and the lower Chesapeake.

Not enough is known to provide a firm local attribution for this chair, which was first published in the query section of The Magazine Antiques in August 1926 and later appeared in Paul Burroughs, Southern Antiques (1931). Although no historical data was recorded in either source, both hint that the chair was found in South Carolina. That scenario would explain the French character of the back design. Black walnut was little used in coastal South Carolina, but it was not unknown there. Continued research may eventually reveal related objects that will permit a more concrete attribution. Regardless of its exact origin, this southern great chair and its complement of costly cushions must have been the most important piece of seating furniture in the gentry home of its first owner.

InscribedNone

MarkingsNone

ProvenanceAntiques dealer Joe Kindig, Jr., York, PA.

An image of the chair appears in a photo taken by J.K. Beard, Richmond, Virginia during the early 20th century (copy in OF - original is in Beard photo collection, CWF).

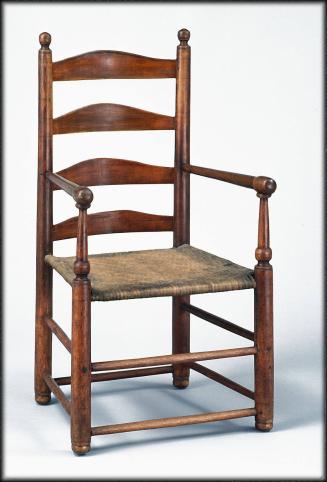

1720-1770

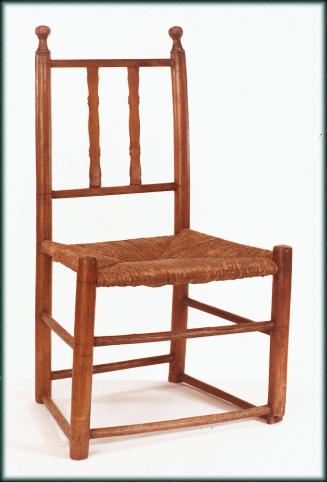

1700-1750

1700-1750

1730-1770

1730-1800

1720-1750

1740-1800

1800-1810

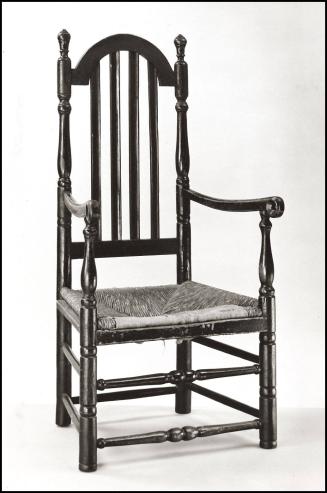

1675-1725

1775-1825

1780-1820

1750-1800