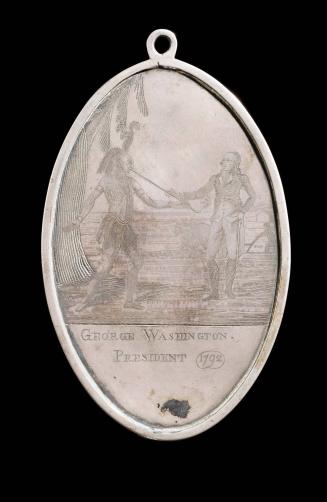

Charleston "FREE" Badge

Date1787-1789

Engraver

Thomas Abernethie

(fl. 1785 - 1795)

MediumCopper

DimensionsOverall: 42 mm x 36 mm; Weight: 227 grains (14.7 grams)

Credit LineMuseum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund and Partial Gift of John Kraljevich

Object number2024-171

DescriptionOval uniface badge struck with a liberty cap & pole emblazoned FREE and surrounded by CITY OF CHARLESTON within a foliate banner, all encircled by a dentiled border. "No.." and "U." engraved to either side of the pole, pierced for suspension at 12:00. Significant traces of engraved currency text (retrograde) on reverse.Label TextWeeks after the Revolutionary War officially ceased by terms of the Treaty of Paris, the newly incorporated city of Charleston, South Carolina began to pass laws. The population of this bustling port city was overwhelmingly African American, and counted more than 8000 people in this community. Of these men, women, and children, the vast majority was enslaved, with only six hundred or so living as free people. Ever fearful of insurrection, the city's administration continued its tradition of implementing policies designed to constrain the lives and activities of all of its African American residents.

An ordinance inked into law on November 22, 1783 regulated the employment or "hiring out" of skilled and unskilled enslaved workers. In this common process, an individual went to work for an entity other than their enslaver, who was paid a fee for the service provided. An annual fee ranging from five to forty shillings was to be paid to the city by the enslaver for the right of an enslaved individual to be hired out, and a badge or ticket was required to be worn by the laborer.

This law went even further, effecting the free African-American population by decreeing;

"....every free negro, mulatto or [mestizo] living or residing within this City, shall be obliged ... to register him, her or themselves, in the office of the City Clerk, with the number of their respective families and places of residence ... every free negro, mulatto, or mestizo, above the age of fifteen years, shall be obliged to obtain a badge from the Corporation of the City, for which badge every such person shall pay into the City Treasury the sum of Five Shillings, and shall wear it suspended by a string or ribband, and exposed to view on his breast."

With these dehumanizing requirements, implemented upon the arrival of peace, Charleston levied a fee on the right of free people of color to live and work in the city. A truly stinging irony when one considers the root causes of the American Revolution. Breaking this law came with harsh penalties. Failure to fully comply could see an offending freeman fined £3, which if not paid within ten days could see them taken to the workhouse (jail) and obliged to work for up to thirty days. Those enslaved individuals caught wearing a "free" badge were subject to whipping, by up to thirty nine lashes, followed by an hour in the stocks.

Though no examples of "slave" badges datable to 1783 have been identified, ten "free" badges from later in the 1780s are known (as of mid-2024). With one exception, all are copper. Their iconography is misleadingly uplifting, featuring the "Phrygian" cap and pole, symbolic of the lofty ideals of liberty since ancient times, rendered in high relief and emblazoned "FREE."

Since these badges were intended as instruments of tracking, control, and a source of revenue, each carries a unique sequential designator. Colonial Williamsburg's badge is engraved "No..U," and is part of a succession, possibly limited to twenty-six or fewer badges, that received letters instead of numbers. To date, the only other badge inscribed with a letter is "No.. X," while the other eight examples are numbered between 14 and 341. On all ten of the badges, "No.." is engraved, as are the numerals for badges 14, 33, 156, and 307. On badges 259, 320, and 341, the numbers are punched in, suggesting this subgroup may be later than the engraved ones. Perhaps badge 307, with its high number, is engraved because it is silver and is thought to be an outlier of intentionally elevated quality.

What further unites badges "U" and "X" are the planchets, or copper pieces, they were struck on. Both exhibit portions of text engraved in retrograde or "mirror image" on their backs, showing that they had previously been part of a printing plate. Once reversed, the readable portions contain words like PENCE, TREASURY, DEPOSIT, and RENTS, offering a smoking-gun clue to their numismatic origin. The only paper money circulating in 1780s South Carolina which carried these specific terms were the City of Charleston's emissions of July 12 and October 20, 1786, only current until July 21, 1788. It can therefore be said with certainty that the badges "U" and "X" were made of copper recycled from the out-of-date printing plates for these two issues.

As of mid-2024, unique examples of only the "Two Pence" and the "Five Shillings & Three Pence" bills from the 1786 issues of Charleston's paper money have been recorded. Being that the text engraved on the reverses of badges "U" and "X" match neither, they were for the printing of bills of unknown denominations that are not known to survive.

A law passed on June 16, 1789 threw out both of Charleston's badge programs for African Americans. When the city re-implemented a drastically expanded system of regulation in 1800, it required the purchase and wearing of badges for enslaved people only. Between then and the end of the Civil War in 1865, more than 187,000 "slave badges" were made, sold, and worn by Charleston's "hired out" enslaved workers.

Though "FREE" badges were never again mandated by the city, the poor condition some of the examples survive in suggests they may have been worn well past their obsolescence. Perhaps their owners sought to display their status as dignified, free individuals, in an open and proud manner for all to see.

Inscribed"No.." and "U." engraved to either side of the pole. Portions of four lines of engraved currency text (retrograde) on reverse. Word and phrase fragments include PENC(E), (TRE)ASURY OF THIS, RENTS & IS(SUES), and (ME)DIUM WITH THE CO(MMISSIONERS).

ProvenanceBefore 1998, unknown second-hand shop (Waterford, TX); Sold ca.1998, along with some "family papers" [eBay] to an unknown antique dealer; Sold ca. 2001 to Tony Chibbaro (Prosperity, SC); Sold in 2019 to John Kraljevich (Fort Mill, SC); 2024-present, acquired by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (Williamsburg, VA).

1770-1780

ca. 1775

February 8, 1788

1843-1844

1800-1810

April 3, 1778