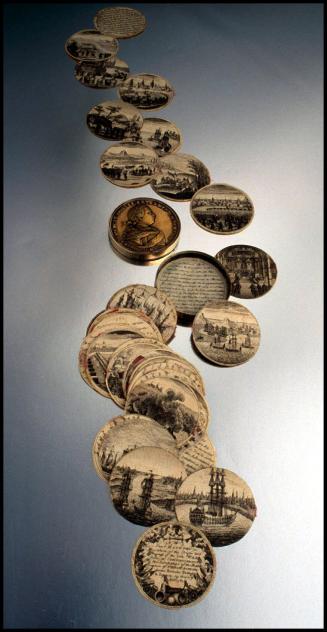

"Louisbourg Captured" award medal

Date1758

Die Cutter

Thomas Pingo

(also designer)

OriginEngland, London

MediumSilver

DimensionsDiameter: 44 mm. (without loop)

Credit LineGift of the Lasser Family

Object number2004-8,55

Label TextFrom the French point of view, the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, between what is now Cape Breton Island and Newfoundland, was the key to the continent. Not that the Mississippi River wasn't highly important to New France, but Quebec, its capitol, was vulnerable to attack from the St. Lawrence. As demonstrated by numerous Anglo-American attempts to take Quebec in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, it became apparent that the mouth of the river had to be fortified. Although settlers arrived there as early as 1713, the site of what was to become the town & fortress of Louisbourg was selected to be the seat of government of Cape Breton Island (called Isle Royale by the French) four years later. In 1719, work on the fortifications began with the King's Bastion, and the following year a medal was struck to commemorate the founding and fortification of the town.By 1745, Louisbourg was a sizeable town of a few thousand with strong fortifications and some 1500 soldiers & militiamen available for protection. With the War of the Austrian Succession raging, Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts, decided it was in the Colonies' best interest to take the town - which is just what he did - with the support of the British navy and some 4000 New Englanders under the command of William Pepperell. When the war ended in 1748, much to New England's chagrin, Louisbourg was returned to the French under the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle.

A few years later, with the onset of the French and Indian (or Seven Years) War, the British came to regret that concession. The hub of Britain's plan for the subjugation of Canada was the reduction of Quebec, which necessitated the taking of Louisbourg first. This time it would be far more difficult - the defense of the town now included some 3500 soldiers and 400 militiamen bolstered by 10 ships of war, mounting almost 500 cannon and manned by almost 4000 sailors.

To ensure victory, the British sent a joint force of naval and ground forces. Under the command of Admiral Edward Boscawen was a squadron of 34 "men-o-war" (plus other smaller vessels) wielding some 1700 cannon. The land forces, commanded by General Jeffrey Amherst, were composed of around 13,000 British and American troops. This combined force arrived at Louisbourg in June of 1758 and immediately began the siege, opening their first battery (cannon emplacement) on 19 June. One month later, the fight continued viciously as the British artillery slowly reduced the town and fortress to rubble. By July 26, the French garrison had enough and surrendered, an event commemorated and celebrated throughout Britain and America.

Dies for a dual-purpose medal were almost immediately prepared by Thomas Pingo, with specimens struck in time to be exhibited at the Royal Society of the Arts in the Strand, London in 1760. As some specimens were fitted with a suspension loop while others weren't, it can be assumed it served as both a military award and a commemorative medal.

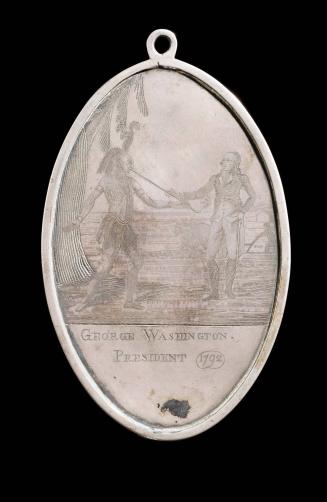

This medal marks a significant departure from the norm in that it illustrates not only an accurate scene from the event, but it depicts a common British soldier and sailor, not in allegorical or classical garb, but in the costume worn during the siege. Furthermore, with the exception of a single Latin phrase on the obverse, the legends are in English.

Pingo's obverse is one of the most bold, busy and interesting compositions to appear on any medal of the period, and would certainly have appealed to both veterans of the siege and contemporary medal collectors. As the iconography & symbolism depicted on the obverse have been discussed in print many times it is not necessary to do so here, so it shall be analyzed as a rare, contemporary document of the appearance of the "Equal in War" British soldier & sailor of the French & Indian War.

At this time period, each regiment in the British army was composed of between 8 and 10 companies, one of which was the elite Grenadier Company, composed of the largest, bravest and best soldiers. It is the grenadier that Pingo chose to appear on his medal, distinguished by his tall, mitre cap and match case. The later piece of equipment is seen attached to his shoulder belt, and due to its diminutive size on the medal, registers not unlike a jalapeno pepper. The match case was an enclosed, vented metal tube that held a piece of burning slow match for lighting grenades - one of the traditional but by then defunct duties of the grenadier. As the elite company of the regiment, the match case was retained as symbol of status. His foot-tall cap made him appear larger, and as it had no side projections (like the common three-cornered "cocked" hat of the common soldier), facilitated the slinging of his musket across his back in order to light & throw grenades. The front of his cap was embroidered with either a regimental device or the Royal cipher, and on Pingo's medal the former is the case. On well-struck specimens, a crowned garter & star, flanked by floral sprigs can be seen. During the siege of Louisbourg, the only regiment present that had a similar appearing badge was the 1st or "Royal" Regiment, and it may be that this represents grenadier is of said unit.

Affectionately nicknamed "Tar" or "Jack Tar," the British sailor of the mid-18th century was not yet officially uniformed, but still wore purpose-inspired clothes that betray his profession. Pingo's sailor proudly waves his round hat, which would have been made out of old, heavy-duty sailcloth waterproofed with a generous coat of tar - thus his nickname. He is portrayed barefoot, as he would have spent much of his time while aboard ship, since shoes are a hindrance when climbing into the rigging or "going out on a yard" to furl or unfurl a sail. Instead of the tight knee breeches, he wears loose fitting "petticoat breeches," also known as "slops." Tucked into his belt is a pair of pistols, and a neckerchief can be seen tied below his chin.

By far, the most commonly encountered medals relating to the 1758 Siege of Louisbourg are those varieties depicting Admiral Boscawen, usually struck in brass or bronze. Aside from the fact that said portraits looks nothing like the man, the reverse is equally inaccurate. In stark contrast to these whimsical depictions of the siege is Pingo's reverse, which when compared to maps and accounts of the event, has proven to be highly accurate.

The scene depicted, one of the most dramatic, if not the most pivotal event in the siege, had also been widely discussed in print, and will be analyzed as an historical document. The view is looking almost due east, over a British battery firing at the fortress, above which is flying a mortar bomb. To the right is the town of Louisburg, whose fortified shoreline is ablaze with cannon fire, as evidenced by the billowing smoke rolling out over the water. Two "shallops" (small boats) are anchored off the closest bastion, which would have been near the Dauphin Gate, the closest land portal to the British lines.

Amongst the identifiable features of the town are the seawall, the King's Barracks & Chapel, which is the large, steepled building at the tail end of the legend, and the two bastions projecting out into the harbor. Off the tip of the furthest bastion is a small rocky island, which looks more like a die void than a geographic feature. Across the mouth of the harbor to the north is Lighthouse Point, on which is built, surprisingly, a lighthouse.

In the distance loom 6 ships of the British squadron blockading the harbor, with their sails furled and cannons brought to bear on the town. The largest ship, third from the right is the HMS Namur, the flagship of Admiral Boscawen, commanded by Capt. Matthew Buckle.

Two French ships, Le Prudent of 74 guns and Le Bienfaisant, 64 guns, appear in the middle of the harbor. The former burns furiously after being torched, while the later, in British hands after an attempted escape, is being towed off towards the north by a dozen small craft. Partially obscured by the puff of smoke from the last British cannon in the right foreground is the hull of one of the three French ships sunk 4 days earlier on 21 July.

It can be said for sure that Pingo had either an accurate map of the siege or some eyewitness accounts from which he created this remarkably accurate scene. If one ventures to the reconstructed town & Fortress of Louisbourg today, and stands about where the western British batteries were, the scene of Pingo's medal will unfold before your eyes, with only a few notable differences. The current lighthouse dates from the 20th century and the vista is much more expansive in reality. At the bottom of the harbor, still visible from the surface under proper conditions, are some of the cannon from Le Prudent, resting exactly where they sank in July of 1758.

Many examples of Pingo's Louisbourg medal were made as collectables, struck in both silver and copper, and fall outside of this study. One of these copper medals should be mentioned however, since it was engraved on the edge "Captain Collings," and was sold as item 9382 in Spink's Numismatic Circular of October 1893. The description made no mention of a suspension loop (other items on the list were described as having loops), so it can be assumed that it was not an award.

Therefore, the presence of a particular type of suspension loop, or provision for it, is key to discerning an award medal from a commemorative one. This particular loop, rightfully described as a swivel, is unique to the Louisbourg award, and is of half-round section with circular terminals. While the metal of its construction parallels that of its host medal, invariably, the pin by which it is affixed to the medal is a tiny iron screw, similar to that used in pocket watches of the period.

As the commissioner of Pingo's Louisbourg award remains obscure, we do not know by what means these medals were distributed to veterans of the event, or, except on rare occasions, exactly to whom. Since specimens are known struck in gold, silver and bronze, it can be assumed that rank had something to with whom got what. Documentary records of medals being worn by rank and file British fighting men during this period do not occur, so it can be assumed that all of these Louisbourg award medals were to be worn by officers.

The existence of at least three provenanced gold medals is known. Two were awarded to Captains of Men-o-War (Matthew Buckle Captain of HMS Namur, 90 guns and Sir Alexander Schomberg of HMS Diana, 32 guns), while the third went to a junior officer, George Young. Senior Midshipman Young, of HMS York, 60 guns, is recorded as having commanded one of a number of British boats responsible not only for the destruction of Le Prudent, but also the capture of Le Bienfaisant. This was an absolutely astounding set of accomplishments, which contributed greatly to victory - and ended up being depicted on the very award medal!

As late as the 1890s, the original ribbon from the Schomberg medal survived, and was described in Tancred as "a much faded riband, rather more than an inch and a half wide. It consists of two colours, one half being tawny yellow, the other bluish purple."

Being that the above shows gold awards went to high-ranking (perhaps only Captains of ships?) & distinguished naval officers, it can be assumed that silver and bronze awards went to more junior officers or those of less distinction. Although no contemporary documentation has yet been discovered which concretely identifies the individual or organization that that commissioned these medals, when Captain Buckle's medal was catalogued for sale in late 2003, it was attributed to Admiral Boscawen. As all three gold specimens discussed have a naval provenance, this may well be the case.

ca. 1720 - 1770

1836-1855

1785-1800

c.1801-09

ca. 1783